SharkGuard technology reduces endangered shark bycatch, sea trials show

Regarding challenges for the seafood industry, IUU fishing, climate change and overfishing are all top of the list. But commercial fisheries face another related but pressing problem: bycatch, or the unintentional capture of non-target marine species that get hooked or entangled in fishing nets or gear.

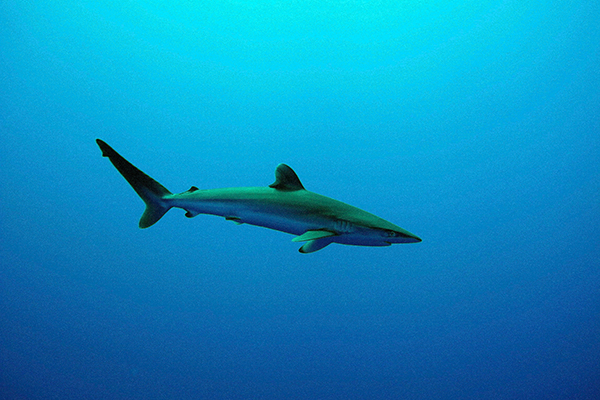

Many marine species are accidentally caught by fishing vessels, but there’s growing concern about the bycatch of endangered sharks. Estimates suggest that tens of millions of sharks are caught as bycatch each year, and a quarter of sharks and rays are now classified as threatened. In fact, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) says most fisheries catch sharks as bycatch, and some fisheries unintentionally catch more sharks than the targeted species.

“Many shark and ray populations are declining due to overfishing – particularly oceanic species such as blue sharks and pelagic stingrays that are commonly caught on longlines globally,” said Dr. Phil Doherty, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation. “There is an urgent need to reduce bycatch, which not only kills millions of sharks and rays each year, but also costs fishers time and money.”

Switching to more selective, efficient gear – changing the shape and size of hooks, bait and depth and length of gillnets and longlines – can help minimize shark bycatch. A 2022 study found that switching from wire to monofilament leaders reduced the catch rate of sharks by approximately 41 percent and still maintained catch rates of the target species (bigeye tuna).

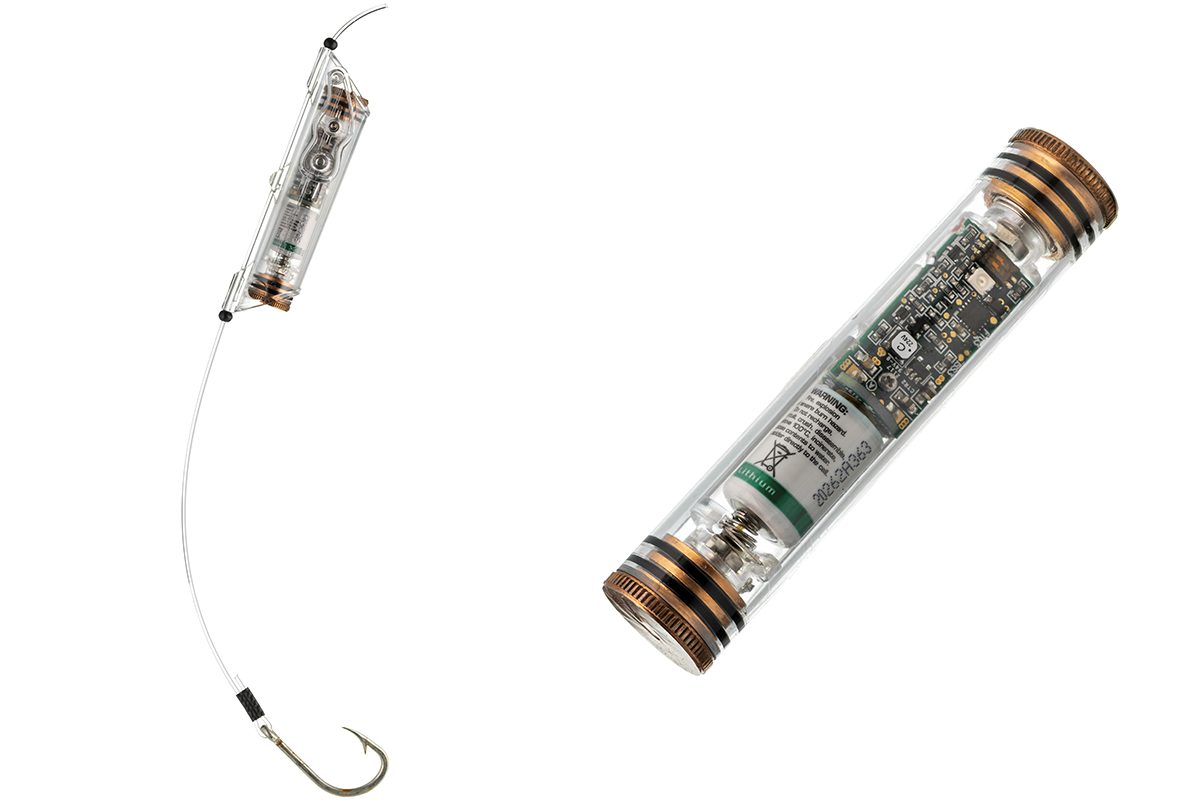

But a new gadget could be a game-changer for the seafood industry. SharkGuard, a device that attaches to longline fishing rigs, emits small electrical pulses to scare off sharks and rays. The device discourages sharks and rays, which detect the electric signals via their electroreceptors, from biting without getting in the way of hooking other fish. Developed by UK-based conservation engineers Fishtek Marine and tested by University of Exeter researchers, recent trials indicate that this innovation can drastically cut the number of sharks and stingrays accidentally caught on fishing lines.

“When SharkGuard is used, sharks do not take the bait and do not get caught on the hooks, and that gives us a huge sense of hope,” said Pete Kibel, co-founder and director of Fishtek Marine.

Hooking onto the right solution

In general, the risk of bycatch largely depends on the fishing method used. For instance, purse seine fishing is quite low – ranging from less than 1 percent to as high as 8 percent – whereas harvesting tuna catch via longlines can yield as much as 20 percent bycatch.

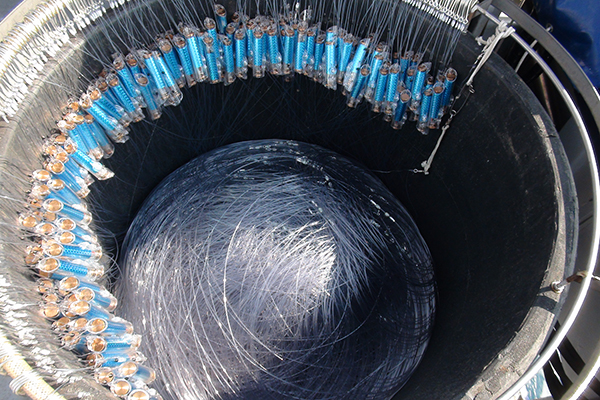

For sharks in the open ocean, longline fishing is the top threat, with an estimated 20 million pelagic sharks caught annually by fishers looking for tuna and other desired species. Longlines are comprised of a mainline that can extend for miles, suspended beneath the surface or close to the seafloor, with thousands of hooks dangling from the mainline.

With more than 100 million sharks, skates and rays caught each year by the world’s commercial fisheries, Fishtek Marine sought to find a solution to slow or even reverse the decline in global shark populations. Looking at shark deterrents that showed promise for protecting scuba divers and surfers, the team speculated that such technology could have a similar application in tuna fisheries to protect sharks from bycatch.

The concept led to the development of SharkGuard. The device, which is powered by a small battery, works by targeting the area around a shark’s nose and mouth, which is packed with electrical sensors called the ampullae of Lorenzini. These sensory organs get overstimulated by the electric field generated by SharkGuard, which makes the sharks swim away from the danger of the baited fishing hooks.

To test the technology, the research team ran sea trials in July and August 2021 in southern France. Two fishing vessels fished 22 longlines on 11 separate trips, deploying a total of more than 18,000 hooks. Carried out on French boats fishing for tuna, the study’s findings revealed that lines fitted with SharkGuard reduced bycatch of blue sharks by 91 percent and stingrays by 71 percent.

“Our study suggests SharkGuard is remarkably effective at keeping blue sharks and pelagic stingrays off fishing hooks,” said Doherty. “Research will continue at Exeter, where we test SharkGuard’s effectiveness at sea across multiple species and fisheries.”

Commenting on the reduced catch of bluefin tuna (42 percent), Doherty said the total number caught in the test period (on both lines with and without SharkGuard) was low, so further trials are needed to fully explore the results.

“We need further testing and development of SharkGuard, but it has the potential to be a global game-changer for the sustainability of longline fishing,” said Professor Brendan Godley, who leads the Exeter Marine research group.

‘There is hope’

Compared to catching and releasing bycaught species including sharks, the researchers said that SharkGuard offers a more comprehensive solution. If its use were scaled up to the level of whole fisheries, it would mean reduced interaction between sharks and fishing gear.

“The main implication is that commercial longline fishing may continue, but it won’t always necessarily result in the mass bycatch of sharks and rays,” said Robert Enever, head of science and uptake at Fishtek Marine. “This is important in balancing the needs of the fishers with the needs of the environment and contributes to national and international biodiversity commitments for long-term sustainability.”

The device has some limitations, including the need for frequent battery changes. The research team is now working to overcome this barrier, so fishers could “fit and forget” it, while still protecting sharks and other bycatch species.

“On the back of these exciting results, the engineers at Fishtek Marine are modifying SharkGuard so it is smaller and self-charging after every haul,” said Doherty.

Another issue to tackle is cost. It’s expected that a full set of induction-charged SharkGuard devices for 2,000 hooks would cost around $20,000, which would last three to five years (roughly $4,000 to $7,000 annually). However, the research team says it’s a “modest annual cost for most commercial tuna fishing operations.”

In the meantime, FishTek Marine has invited fishers who experience high shark and ray bycatch, as well as retail businesses intent on improving the sustainability of their supply chains, to contact their team, as sea trials and engineering developments are planned for commercialization.

“Against the relentless backdrop of stories of dramatic population declines occurring across all of our marine species, it is important to remember that there are people working hard to find solutions,” said Doherty. “SharkGuard is an example of where, given the appropriate backing, it is possible to roll the solution out on a sufficient scale to reverse the current decline in global shark populations.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lisa Jackson

Associate Editor Lisa Jackson is a writer who lives on the lands of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations in Dish with One Spoon territory and covers a range of food and environmental issues. Her work has been featured in Al Jazeera News, The Globe & Mail and The Toronto Star.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

Fisheries management help tunas, billfishes recover, but extinction risk of sharks rises

New study suggests conservation and fisheries management help tunas and billfishes recover, but shark biodiversity continues to decline.

Fisheries

Bangladesh moves to protect threatened sharks and rays

With sharks and rays critically endangered, the government of Bangladesh has amended legislation to reduce the extinction risk of the species.

Fisheries

Canadian government combats IUU fishing with Operation North Pacific Guard

Operation North Pacific Guard, an annual international law enforcement operation in the North Pacific, aims to detect and deter IUU fishing.

Innovation & Investment

Exit stage right: Fish 2.0 offers final set of winning innovators

Nearly 40 entrepreneurs took the stage to pitch their seafood industry-changing innovations in front of a room full of discriminating investors.