Why farm Penaeus esculentus?

Australia has a diverse and abundant fauna of penaeid shrimp. Of the 50 species recorded in Australian waters, however, only P. monodon, P. japonicus and P. merguiensis are currently farmed there. Market research indicates that a strategic approach to species diversification is essential for the long-term viability of the Australian shrimp farming industry.

With funding from the Australian Fisheries Research and Development Corp., aquaculture scientists from CSIRO Marine Research are assisting shrimp farmers in meeting the need for diversification. Their research on the brown tiger shrimp, an attractive, striped species endemic to Australia, promotes P. esculentus as an attractive production alternative to traditional species if appropriate farming techniques can be developed.

In Australia, the brown tiger shrimp is a commercially important species with a wide natural distribution and extended spawning season. It has well-established export and domestic markets, but wild fisheries cannot always meet market demand. This is an opportunity for aquaculture producers to diversify production and enter the markets created by the wild fisheries.

P. esculentus obtains higher prices in the domestic market than the widely farmed P. monodon. In addition, P. esculentus can be cost-effectively sold into an export market, which is difficult to achieve for Australian-grown P. monodon.

Commercial farm grow-out performance

Commercial trials under intensive farming conditions (29 to 34 shrimp per square meter) have shown that P. esculentus grown to marketable size (25 grams) within a normal five-month grow-out season could attract prices similar to the wild-caught product on Japanese and Australian markets (Crocos et al. 2000).

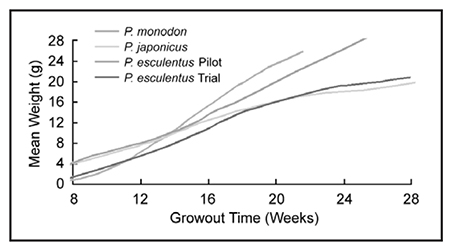

In the past, farm production trials using formulated feeds designed for P. monodon proved unsuccessful for P. esculentus due to the higher protein requirements of the latter. In the newer study, a higher-protein diet was fed to help achieve acceptable growth rates. When compared with the P. japonicus and P. monodon species predominantly grown in Australia, the growth performance of P. esculentus under suitable farming conditions is attractive for commercial production (Fig. 1).

Potential for domestication

The current reliance of the shrimp farming industry on wild broodstock is risky and inefficient, and precludes the opportunity to enhance production through selective breeding and disease management. Farming of P. monodon in Australia is constrained by the limitations of using wild broodstock, which include unpredictable supply and consequent delays in stocking, in addition to potential disease problems. In many countries with substantial shrimp farming industries, particularly those in Asia, belated efforts to domesticate broodstock are now hampered by a very high incidence of viral diseases in farm stocks.

Genetic improvement

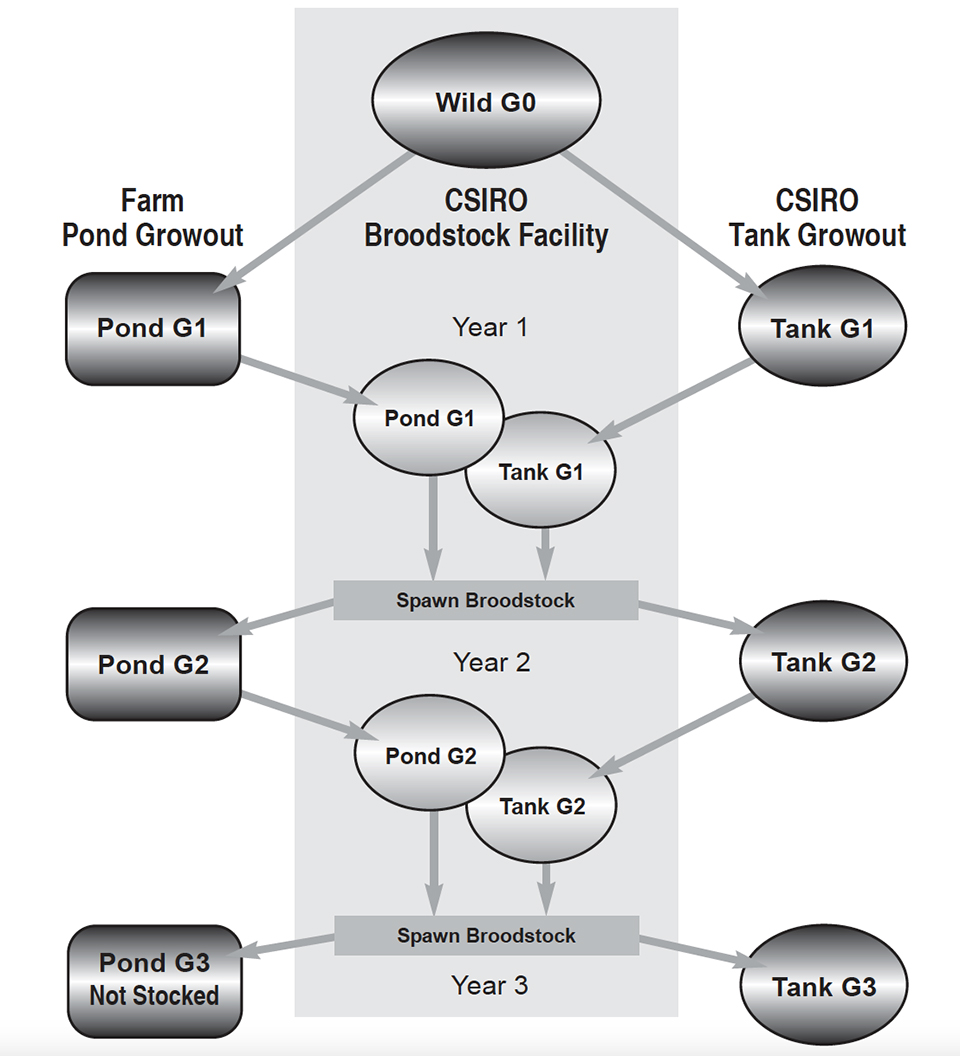

In Australia, research advances by CSIRO in shrimp domestication and selective breeding have placed the country in a favorable position to make rapid advances in genetic improvement of farmed shrimp. For P. esculentus, three generations of viable progeny were produced from domesticated broodstock (Fig. 2) using similar domestication techniques to those developed for P. japonicus (Hetzel et al. 2000).

Generally, one of the main concerns with domesticated stocks has been the perception of reduced reproductive performance. A comparison of wild and domesticated stocks of P. esculentus broodstock demonstrated no difference in the spawning rates and overall egg production (Crocos et al. 2000). The amenability of P. esculentus to domestication indicates this species is ideal for commercial-scale, closedcycle production and subsequent genetic improvement.

Cost-benefit analysis

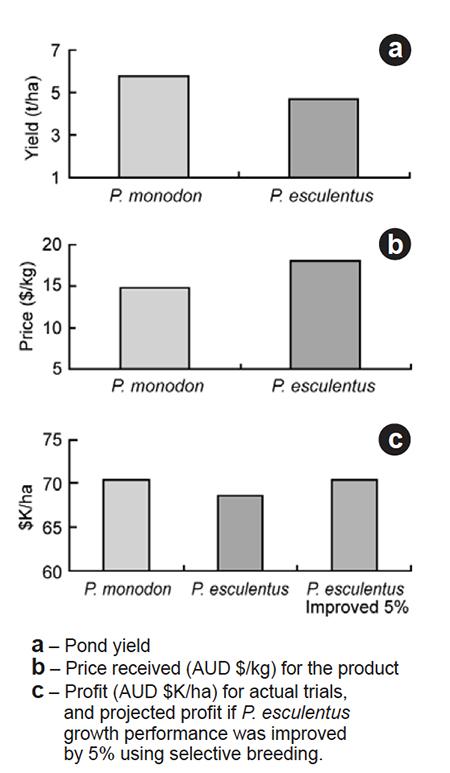

An overall cost-benefit analysis of a “current situation” scenario supports the potential of P. esculentus to be grown in Australia with profitability similar to P. monodon. In this scenario, P. monodon production was shown to be slightly more profitable than P. esculentus (Fig. 3). Although P. monodon consumes more feed and the final product attracts a lower market price than P. esculentus, the P. monodon feed is cheaper, and the shrimp grow slightly faster, resulting in a higher overall profitability. Even so, the difference in profit was less than would be predicted when simply comparing the growth rates observed in the trials.

The higher price received for P. esculentus (AUD $18 per kg) as compared to P. monodon (AUD $14.89 per kg) partly outweighed the lower growth performance. More importantly, the demonstration of the capacity for closedcycle production of P. esculentus has confirmed the potential to achieve growth improvements for P. esculentus that would effectively close this profitability gap.

Analysis suggests that only a 5 percent improvement in growth for P. esculentus is needed to achieve the same profitability as P. monodon (Fig. 3). This could be achieved with selective breeding and/or the continued development of a cost-effective specific diet for this species.

Broader applications for production technology

The development of culture techniques for P. esculentus has become a critical component of research to evaluate the potential stock enhancement of this species in wild fisheries and ensure the fisheries’ sustainability. Mass rearing systems at ultra-high densities (up to 4,000 PL per square meter) are being developed for the production of juvenile P. esculentus for release into fisheries recruitment areas. Preliminary results indicate P. esculentus juveniles are suitable for this type of rearing.

Conclusion

CSIRO research has confirmed the potential for P. esculentus to be grown as an additional species by Australian farmers. Overseas markets have shown strong demand for farmed P. esculentus product. Continued advances in selective breeding and diet development can further the cost-effective farm production of this species. Note: Cited references available from the authors.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the December 2000 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Sandy Keys

CSIRO Division of Marine Research

P.O. Box 120 - Cleveland, QLD Australia[117,97,46,111,114,105,115,99,46,101,110,105,114,97,109,64,115,121,101,107,46,97,114,100,110,97,115]

-

Peter Crocos

CSIRO Division of Marine Research

P.O. Box 120 - Cleveland, QLD Australia[117,97,46,111,114,105,115,99,46,101,110,105,114,97,109,64,115,111,99,111,114,99,46,114,101,116,101,112]

-

Nigel Preston

CSIRO Division of Marine Research

P.O. Box 120 - Cleveland, QLD Australia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Sexual growth dimorphism in penaeid shrimp

Sexual growth dimorphism occurs in cultured aquatic species like tilapia, catfish and salmon, and has also been reported for cultured crustaceans.

Health & Welfare

Zero exchange, aerobic, heterotrophic systems: key considerations

Most environmental concerns about aquaculture practices can be addressed effectively by zero exchange, aerobic, heterotrophic culture systems.

Health & Welfare

CSIRO research evaluates technologies to produce genetically protected, all-female shrimp

In Australia, CSIRO is investigating techniques to produce reproductively sterile, all-female shrimp populations through polyploidy, irradiation, or genetic engineering.

Aquafeeds

CSIRO studies dry feeds for juvenile spiny lobsters

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation has researched pelleted dry feeds are palatable to juvenile tropical spiny lobsters.