Sea bass is now considered a priority species for aquaculture

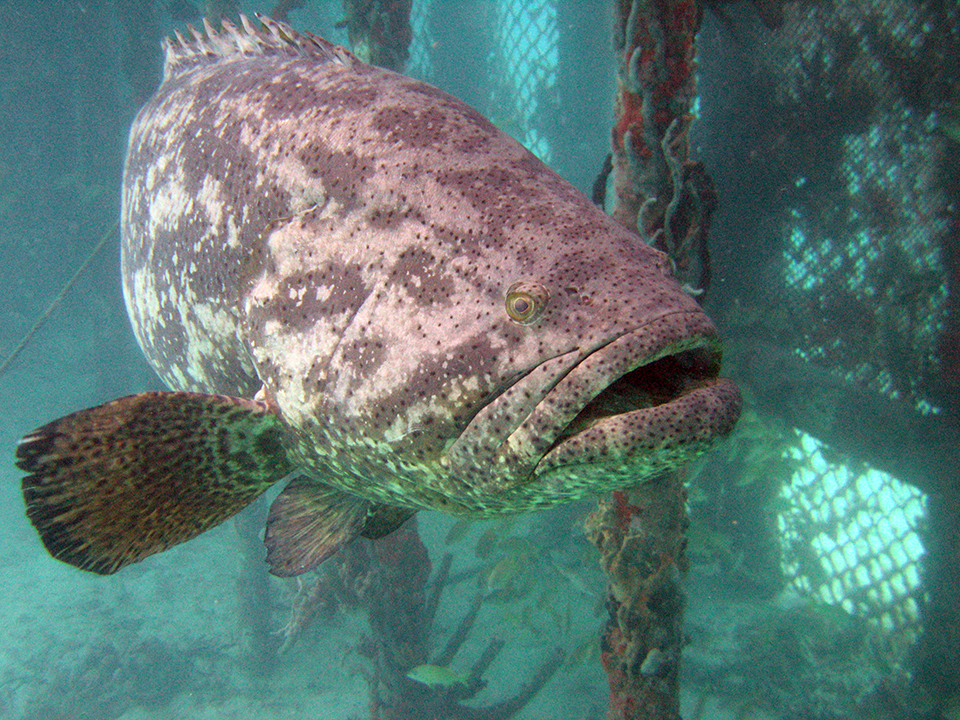

The fast-growing totoaba is now considered a priority species for aquaculture in Mexico.The totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) is a carnivorous sciaenid fish endemic to the Gulf of California in Mexico. The species is one of the largest sciaenids, reaching up to 2 meters in length and 136 kg in weight, with a steel-blue color and small black spots during the juvenile stage. Adults migrate annually during the fall from south to north through the Gulf of California, and during the winter, they arrive at their reproduction and nursery area near the Colorado River Delta, between the states of Sonora and Baja California, Mexico.

The fishery of totoaba was one of the most important activities in the area during the 1920s, and because of the species’ abundance, the first human settlements along the coastline of Sonora and Baja California were established. However, since the 1940s and up to the 1970s, a significant reduction of their natural stocks by overfishing was evident, since large amounts of totoabas were captured throughout the Gulf of California just to extract their swim bladders, which were mainly exported to Asia. The rest of the animals, including the fillets, was usually discarded into the ocean.

In addition to overfishing, the ecological alterations of the Colorado River Delta and the by-catch of totoaba juveniles led the species to the brink of extinction. Measures were taken, and the fishery of this species was completely and indefinitely banned since 1975, followed by the inclusion of totoaba on the Mexican government’s list of endangered species in 1994.

Recovery of wild stocks

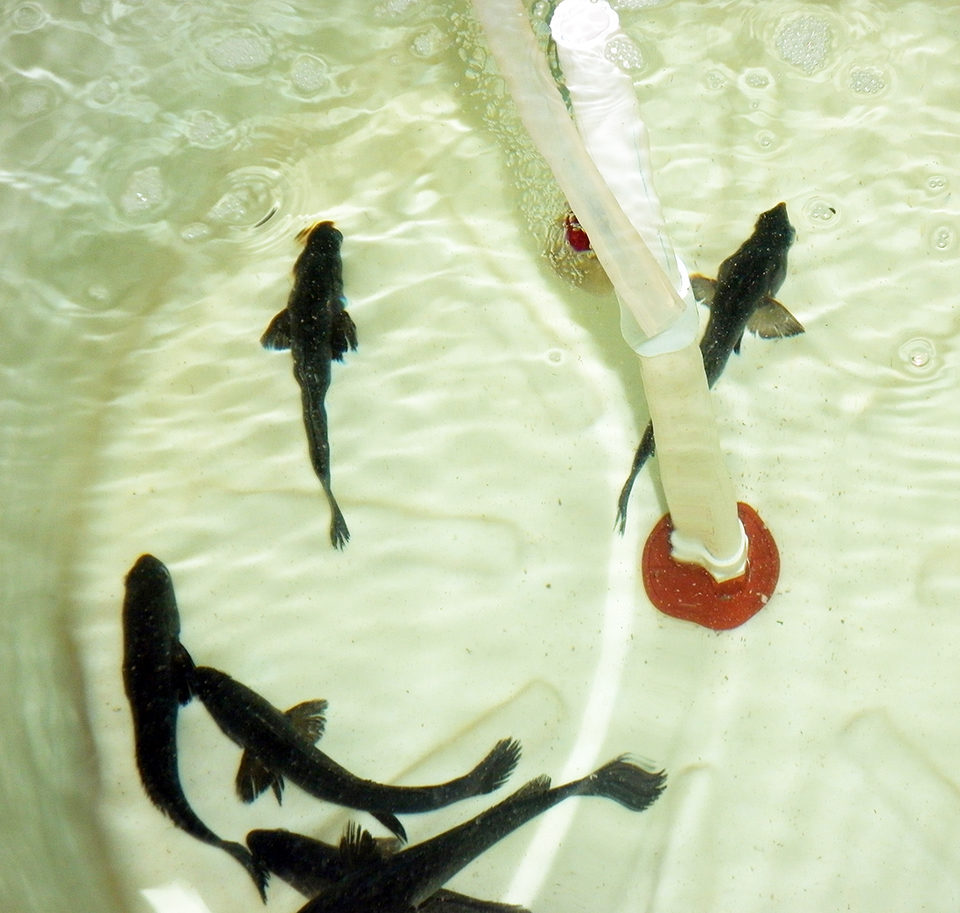

A totoaba breeding and aquaculture program was created by the Mexican government in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, 20 years ago to help the development of restocking programs for the recovery of wild stocks. The program has shown moderate success in broodstock management and juvenile production.

Nowadays, the importance of the project has grown due to the interest of entrepreneurs in totoaba’s great aquaculture potential as a fast-growing species. Totoaba fillets are highly appreciated in national and international markets, and the swim bladders of the fish can be commercialized individually in the Asian market, where high prices are easily reached.

The government program recently expanded with the addition of another laboratory, the Center for Reproduction of Marine Species of Sonora State (CREMES) at Kino Bay, Sonora, which also achieved reproduction and larviculture of totoaba in captivity. The federal and state governments allowed the institution to catch wild fish in the Gulf of California, which were acclimated to laboratory conditions and spawned viable eggs after a year of adequate husbandry and nutrition. Rearing of the progeny is currently under way.

This is the first time totoaba have been successfully reproduced in captivity outside the state of California, which opens new possibilities for expansion of the breeding program for this species. In addition, pilot-scale efforts have been carried out rearing totoaba in sea cages near Ensenada, on the Pacific west coast of Baja California, and within the Gulf of California in La Paz, Baja California Sur, and in Guaymas, Sonora, over the last three years. Although results have been promising in terms of the fast growth rates observed, fish in these trials have been fed commercial aquafeeds for other species, which do not necessarily meet the specific nutritional requirements for this species.

Thus, research to determine the nutritional requirements of totoaba is of great importance in developing suitable formulations that will allow the species to reach its growth potential in aquaculture systems. This goal is currently being cooperatively pursued by the Department of Scientific and Technological Research at the University of Sonora, the University of Baja California, the Ensenada Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education (CICESE), and CREMES.

Initial studies: protein requirements

An eight-week experiment was performed at the University of Sonora’s Kino Bay Experimental Station to determine the protein requirements of juvenile totoaba. A total of 120 juveniles with initial mean weight of 74.7 ± 5.3 grams were donated by Pesquera Delly, S.A. de C.V. The fish were randomly and equally distributed in a semi-enclosed recirculating aquaculture system consisting of 24, 250-liter (L) tanks. Three isolipidic diets with 8 percent crude fat were formulated to contain 47, 52 and 55 percent crude protein.

A commercial feed containing 38 percent crude protein and 7 percent crude fat was used as an external reference, but not included in the statistical analysis. Each diet was assigned to six replicates. The feeding rate was adjusted biweekly to provide 5 percent of the biomass daily. The daily ration was divided into three feedings provided at 9 a.m., 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. Dissolved-oxygen levels were maintained above 5 mg/L. Temperature, salinity and pH showed mean values of 28.4 degrees C, 38 ppt and 7.8, respectively, whereas the mean value for ammonia was 0.4 mg NH4-N/L.

At the end of the trial, no statistical difference was observed among the treatments for growth, survival, weight gain or other biological indices evaluated. Totoabas showed a daily weight gain of 2.1 to 2.3 grams and a mean feed-conversion ratio of 2.2. Mean survival was above 97 percent.

Perspectives

Results obtained in this initial study were promising and showed the potential for this species as comparable to that of red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) another sciaenid commercially cultured worldwide. Totoaba is now considered a priority species for aquaculture in Mexico, and efforts to establish this industry are being made by government agencies in collaboration with research institutions. Soon, commercialization of totoaba will hopefully be done without harming wild stocks.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 2014 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Authors

-

M.C. Christian Minjarez-Osorio

Departmento de InvestigacionesCientíficas y Tecnológicas

Universidad de Sonora

Edificio 7-G

Blvd. Luis Donaldo Colosio s/n

e/Sahuaripa y Reforma

Col. Centro, C.P. 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico -

Mayra Lizett González, Ph.D.

Departmento de InvestigacionesCientíficas y Tecnológicas

Universidad de Sonora

Edificio 7-G

Blvd. Luis Donaldo Colosio s/n

e/Sahuaripa y Reforma

Col. Centro, C.P. 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico[120,109,46,110,111,115,117,46,115,117,116,99,105,100,64,101,108,97,122,110,111,103,109]

-

Martin Perez-Velazquez, Ph.D.

Departmento de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas

Universidad de Sonora

Edificio 7-G

Blvd. Luis Donaldo Colosio s/n

e/Sahuaripa y Reforma

Col. Centro, C.P. 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Aquaculture gives endangered totoaba a fighting chance

The tenuous fate of a pint-sized porpoise, the critically endangered vaquita, is linked to a fish targeted by poachers fueling China’s appetite for maws. The vaquita remains in peril, but aquaculture presents some hope for the totoaba.

Intelligence

A motive, and a market, for farmed fish in Mexico

Boasting ample areas for aquaculture and a robust domestic demand for seafood – not to mention its close proximity to the U.S. market – a land of opportunity lies in Mexico. Fish farming is primed to meet its potential south of the border.

Intelligence

Un motive, y un mercado, para los peces cultivados en México

Con amplias áreas para la acuacultura y una sólida demanda interna de pescados y mariscos – sin mencionar su cercanía con el mercado de los Estados Unidos – una tierra de oportunidad se encuentra en México. La piscicultura está preparada para satisfacer su potencial al sur de la frontera.

Innovation & Investment

Colombia to diversify its aquaculture industry through marine fish culture

A collaboration among the Center for Aquaculture Research in Colombia, Center for Research, Education and Recreation, and University of Miami is working to adapt the latest aquaculture technology available worldwide to local conditions and create opportunities for farming new commercial species in Colombia.