Tracking fishing fleet movements via VMS data can quickly reveal ecological impacts of marine heatwaves

A recent study has found that shifts in the movement of commercial fishing fleets can provide early warning of broader changes in marine ecosystems.

Using satellite-derived vessel monitoring system (VMS) data, researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz found that fleet movements closely tracked changes in tuna distribution, revealing the ecological impacts of marine heatwaves sooner than traditional indicators.

The researchers found that analyzing global VMS data was six times more effective at predicting shifts in tuna distribution than sea-surface temperature anomalies, a metric commonly used to assess environmental change.

“We have so much data on fishing vessel activity,” said Heather Welch, lead researcher and an associate specialist at the Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS). “These data are traditionally used for surveillance, and it is exciting that they may also be useful for understanding ecosystem health.”

The analysis centers on 2023, when unusually warm ocean temperatures dispersed albacore tuna across the North Pacific, making the fish more difficult and costly to target. Low harvests that year led state governors in 2024 to request a federal fisheries disaster declaration to support the albacore fishery.

In the study, researchers note that the request came more than a year after the fishing season ended. They found that near real-time VMS data showed fleets traveling farther in search of fish, a signal of changing marine conditions. The researchers identify this as the study’s central finding: that fishing fleets can act as ecosystem sentinels, revealing environmental shifts as they occur.

The concept of “ecosystem sentinels” – living sensors that reflect changing environmental conditions – has gained traction among researchers studying ecosystems that are difficult to observe directly. The approach has been applied to animals ranging from birds to whales.

Putting IUU fishing on the map: Global Fishing Watch intends to bring the invisible into view

“Animals have been forewarning risk going back to the canary in the coal mines,” said Elliott Hazen, adjunct professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “So when sentinels help us get out in front of ecosystem change, that both helps protect species and can save time and money.”

While marine apex predators have often been highlighted as effective sentinels, the researchers argue that fishing fleets may offer a comparable signal. Because fishermen closely track environmental conditions that affect catch success, their movements can reflect ecological change, particularly when those shifts affect economic outcomes.

“Fishermen can have wide-ranging movements allowing them to effectively sample large portions of the seascape,” stated the authors. “Importantly, fishermen are conspicuous and their activities are actively monitored via several near real-time, high-resolution data streams including vessel tracking systems, satellite mapping and shoreside landing receipts.”

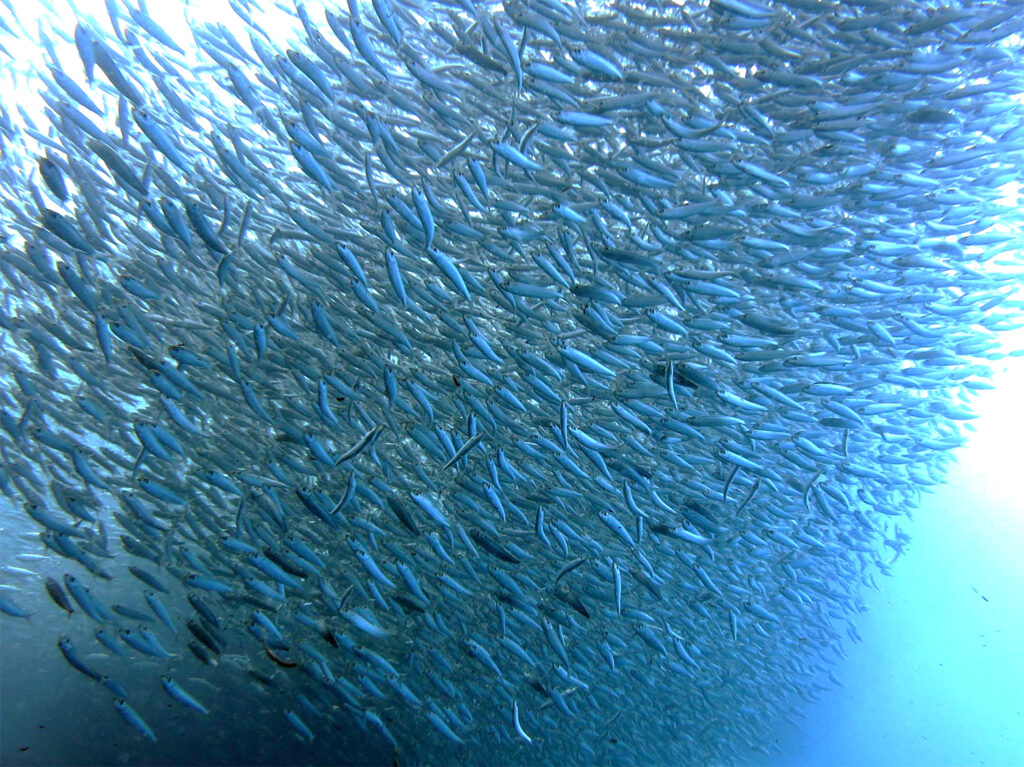

The study focuses on albacore and bluefin tuna, migratory species targeted by West Coast fisheries during summer and fall. Using VMS data, researchers found that both tuna and fleets shifted north during a 2014 to 2016 marine heatwave but remained closer to their typical ranges during heatwaves in 2019 and 2023.

According to co-author Allison Cluett, climate change is disrupting the relationship between environmental indices and ecosystem state, weakening the reliability of temperature-based indicators alone.

“As warming produces unexpected ecological responses to environmental variability, real-time observations of ecosystem health – such as those provided by fishing vessels – are increasingly important,” said Cluett, an assistant project scientist at IMS.

The researchers note that the approach has limitations. Fishery management actions, such as area closures or changes to catch quotas, can influence fleet behavior and complicate interpretation.

“Noise isn’t a reason to disregard this incredibly rich volume of data,” Welch said. “But it does mean we need to carefully review inferences from fishery sentinels to prevent noise from causing harm.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Responsible Seafood Advocate

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,114,111,116,105,100,101]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

The ocean is getting darker. What could that mean for global fisheries?

As a darkening ocean threatens to reshape marine ecosystems, scientists explore risks for fisheries and how rewilding with restorative aquaculture could help.

Fisheries

Tuna fisheries most at risk from climate change, new research suggests

A global study warns tuna and other migratory fisheries face the greatest climate risks as warming seas shift stocks and strain management.

Fisheries

‘Who will win and who will lose?’ How climate change is shifting the ocean food chain – and potentially global fisheries

Climate change is shifting the foundation of the ocean food chain, potentially but not definitively causing a poleward migration of fisheries.

Fisheries

Impact of climate change and economic development on the catches of small pelagic fisheries

An understanding of the impacts of climate change and economic expansion on small pelagic fisheries offers insights for scientific fishing strategies.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)