Research shows that aquaculture can contribute to mitigating carbon dioxide emissions

With the right practices in the right places, aquaculture has the potential to be one of the lowest impact forms of food production, generating fewer greenhouse gas emissions than fisheries or agriculture.

Seaweed and shellfish may prove valuable in the fight against climate change, but a new research model shows that fish farms, too, could provide climate solutions. According to Mojtaba Fakhraee, assistant professor at the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Connecticut, iron sulfide enhancement in fish farms could sequester hundreds of millions of tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) each year.

While aiming to capture CO2 on fish farms, Fakhraee and his team also want to address a particular problem that these farms create: the production of hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas that builds up when microbes in low-oxygen environments like sediment feast on organic matter, such as fish feces and excess feed from farms. High levels of hydrogen sulfide significantly impact the wider marine environment and fish yields, in some cases causing fish mortalities.

However, iron reacts with hydrogen sulfide to form iron sulfide, a mineral that can be sequestered in the sediment beneath a fish farm. Iron sulfide also raises the alkalinity of the surrounding water, resulting in more capacity for the water to sequester CO2.

Unlike iron fertilization, a geoengineering technique that can increase algal blooms, the model developed by Fakhraee and his team focuses on adding iron directly to sediment. It simulates carbon, iron and sulphur cycling in marine sediment under a range of conditions on farms in different countries. Results show that at least 100 million tons of CO2 could be sequestered each year in aquaculture-intensive countries such as China, Indonesia and India. China, in particular, could be an ideal location for the technique to work, due to its large iron industry and abundant fish farms.

“It may seem unlikely, but fish farms are actually good sites for capturing CO2,” Fakhraee told the Advocate. “Aquaculture is a growing sector and there is a strong interest in farmed fish as part of a healthy, sustainable diet. We need to think about other ways to remove carbon from the atmosphere, so why not use fish farms?”

One key aspect of this work is the involvement of farmers. Fakhraee and his team are planning field trials to obtain accurate measurements of hydrogen sulfide on farms and better understand the likely scenarios, consequences and challenges around iron enrichment. Data from farmers on how much hydrogen sulfide their farms produce and how fast this builds up will be used to estimate how much iron will be required. The team will also engage with key stakeholders on how applicable their model might be and want to encourage farmers to get in touch to participate.

“The idea is to help farmers reduce hydrogen sulfide on their farms while explaining the potential of this to mitigate climate change,” said Fakhraee. “So far, farmers in Indonesia have been open to the idea, while some startups have expressed interest.”

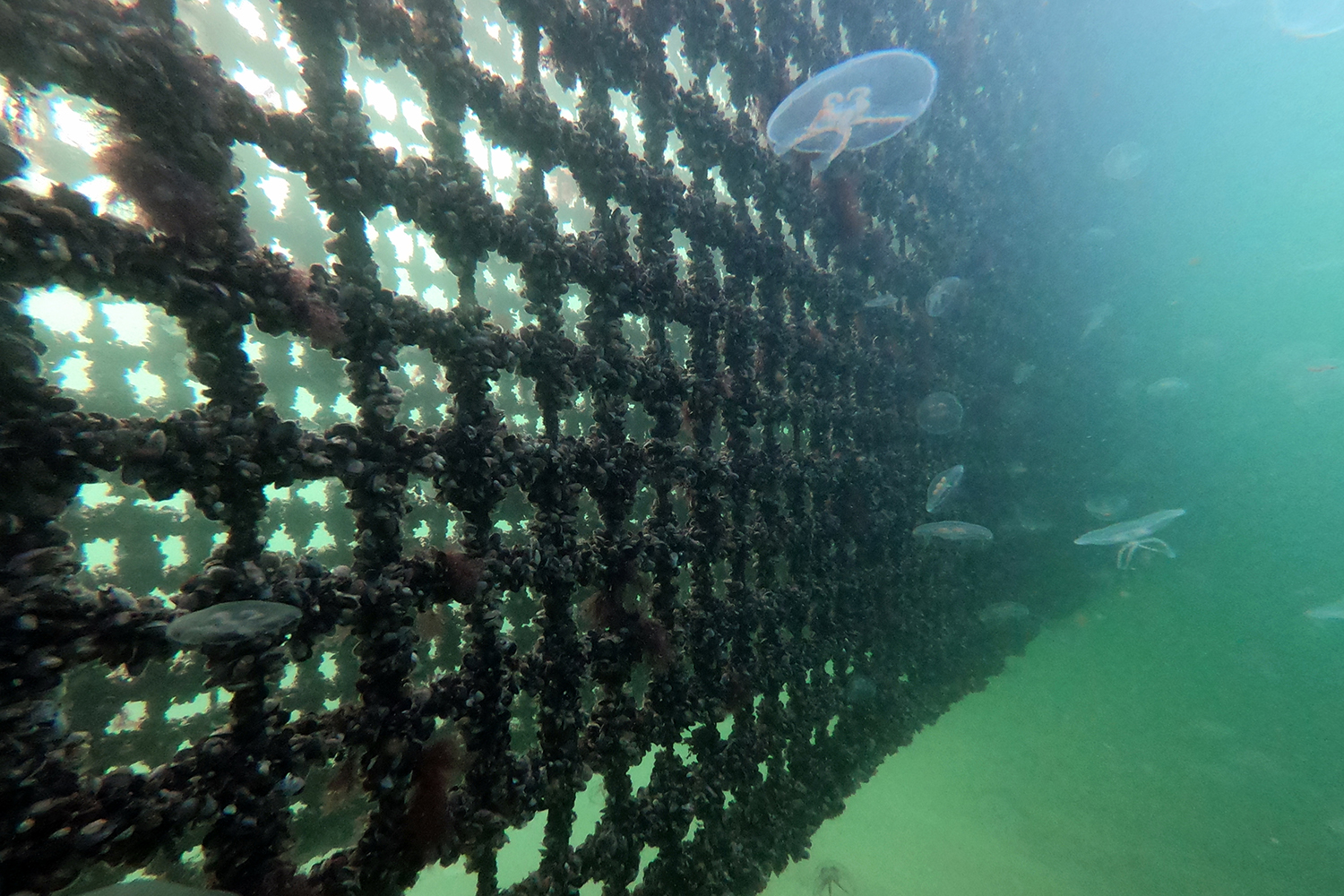

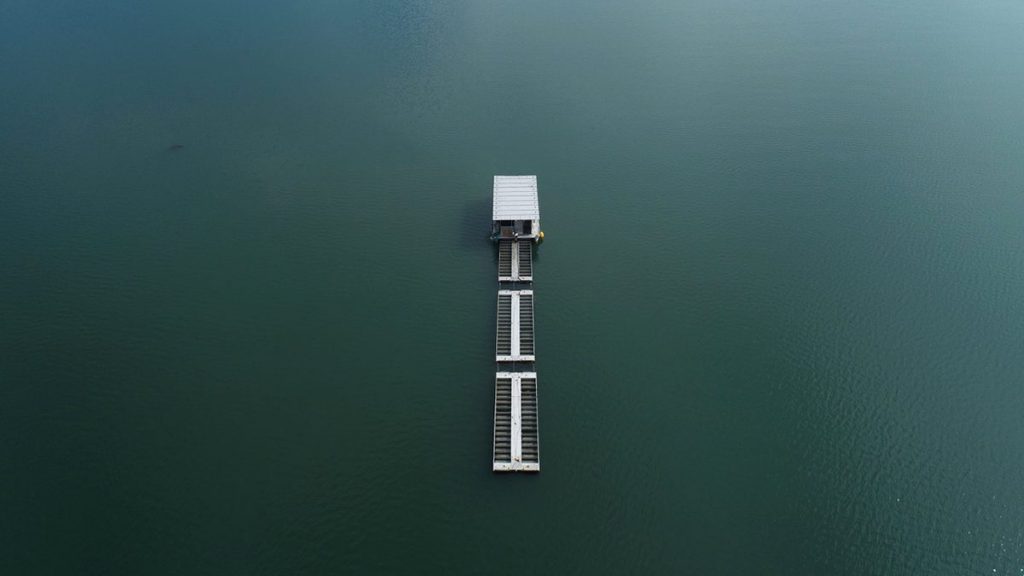

Meanwhile, researchers in Belgium and Estonia have been mapping the carbon capture of blue mussels in the Baltic Sea using a dynamic energy budget (DEB) model, which describes how organisms acquire and use energy and matter throughout their life cycle. It can predict the plausible fate of energy and matter in any organism, including mussels, under varying environmental conditions.

“Climate change is a huge problem in the Baltic Sea,” said Annaleena Vaher, marine ecology specialist at the Estonian Marine Institute at the University of Tartu in Tallinn, Estonia. “Heatwaves are lasting longer, and water temperature and salinity are changing. We wanted to find out if mussels in the Baltic Sea could mitigate the effects of climate change by sequestrating carbon inside their shells.”

“Our model can separately simulate the accumulation of biomass and carbon in both the mussel’s soft tissue (meat) and shell,” said Jonne Kotta, professor at the Estonian Marine Institute at the University of Tartu. “This separation is crucial because the shell, composed of calcium carbonate, represents a pathway for long-term carbon capture if it is removed from the ecosystem. By tracking these components individually, our model provides robust, process-based predictions of mussels’ potential to sequester carbon over time.”

The team found that in the western Baltic, where salinity levels are higher and conditions more favorable, mussels can grow more efficiently and capture a significantly large amount of carbon through shell formation. Regions with higher salinity consistently show higher carbon capture rates due to better mussel growth and shell formation, said Kotta, but local factors such as water temperature and food availability can also influence outcomes. In some cases, favorable local conditions can partially compensate for the limitations of low salinity. Careful selection of farming sites, based on a combination of environmental variables, can greatly improve the performance and carbon capture potential of mussel farms.

Are giant kelp forests carbon sinks? Environmental DNA technology offers clues

Vaher, Kotta and their team are also planning to engage farmers in their work.

“For many farmers, carbon capture may sound a bit theoretical or distant from their day-to-day operations,” said Kotta. “However, our model is currently being used to predict biomass yield and proving useful in supporting more informed, productive farming practices. Climate-related applications may take more time to gain traction, but as a mussel farmer myself, I am optimistic that farmers will come on board.”

Farmers can play a part by providing insights such as local conditions and farming practices that can determine opportunities for carbon capture technology, including the DEB model, said Vaher. Meanwhile, the team has established a community of practice in the Estonian western islands focused on sustainable solutions. The group consists of dedicated individuals who meet regularly to exchange new data, information and tools, and has proven highly effective for co-developing initiatives with farmers and industry representatives.

The team has also developed several web-based decision support tools, similar to Google Translate, that are designed to translate complex scientific analyses into formats that are easy to understand and act upon and tailored to different stakeholder groups. The aim is to deliver solutions that are simple but not simplistic, said Kotta, making cutting-edge science usable and useful for real-world decision-making.

Iron enrichment is also simple, and doesn’t require any complex engineering system. Farmers have been facing issues with hydrogen sulfide for a long time.

“Our model can be readily adapted to other regions and likely to other species,” said Kotta. “In future, we can apply the same framework to conduct similar analyses globally, including for other key aquaculture species, thereby supporting broader assessments of carbon dynamics in aquaculture.”

Fakhraee adds that farmers are likely to be interested in carbon capture if they know that there are low-cost, easy-to-implement mitigation strategies available and that these provide co-benefits.

“In the case of iron enrichment, the co-benefit is removing the build-up of hydrogen sulfide,” he said. “Iron enrichment is also simple, and doesn’t require any complex engineering system. Farmers have been facing issues with hydrogen sulfide for a long time. To know that there’s a way to address this problem, while sequestering carbon, is a way for them to become engaged.”

Kotta says that work such as his and Fakhraee’s are huge first steps in providing farmers with services that are grounded in cutting-edge theoretical frameworks. However, there is still much work ahead.

“The discussion around carbon capture in the shellfish farming sector, particularly mussels, remains highly controversial and filled with uncertainties,” he said. “It is crucial to recognize that the answers depend on the timescales considered and the specific processes influencing carbon dynamics. Continued work is needed on refining ecosystem-level models, integrating carbon dynamics and adapting models for different species and regions, all of which are essential to meet the growing demand for sustainable and climate-smart aquaculture solutions.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Bonnie Waycott

Correspondent Bonnie Waycott became interested in marine life after learning to snorkel on the Sea of Japan coast near her mother’s hometown. She specializes in aquaculture and fisheries with a particular focus on Japan, and has a keen interest in Tohoku’s aquaculture recovery following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Deep-ocean seaweed dumping for carbon sequestration called questionable, risky and not the best use of valuable biomass

Study: Without sound science on the impacts to fragile ecosystems, seaweed carbon sequestration distracts from more effective interventions.

Innovation & Investment

This Maine company thinks kelp buoys and oyster farming can save the ocean through carbon capture and sequestration

Maine-based Running Tide uses carbon-capture and oyster farming techniques – using both low and high technology – to restore ocean health.

Responsibility

Aquaculture ponds hold carbon

Although 16.6 million metric tons of carbon are annually buried in aquaculture ponds, estimated carbon emissions for culture species have approached several metric tons of carbon per metric ton of aquaculture product.

Responsibility

Can kelp farming fix the planet? Experts weigh in on promises and pitfalls

How can kelp farming help solve global challenges? A panel of seaweed experts discussed promises, pitfalls and knowledge gaps.