Study critically examines the biodiversity trade-offs of substituting animal protein from marine capture fisheries with terrestrial agricultural sources

Scientists from Australia, the UK, Sweden and the United States have reported that replacing all animal protein from marine fisheries could require roughly an additional 5 million square kilometers of land (more than area of intact rain forest in Brazil) if replaced by the current proportional combination of livestock and poultry.

What’s more, replacing all fish in aquafeeds would result in the need for more than 47,000 square kilometers of new land converted to agricultural production. Policy makers need to consider the implications of restricting the use of fishery resources on global biodiversity beyond measures intended to achieve sustainable use, the scientists argue.

Their study – authored by Duncan Leadbitter (University of Wollongong, Australia), Nicholas J. Aebischer (Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, UK), Neil A. Auchterlonie (University of Southampton, UK), Tim G. Benton (Royal Institute of International Affairs), Halley E. Froelich (University of California, USA), Stephen Hall (Avalerion UK Ltd., UK), Ulrika Palme (University of Technology, Sweden) and Ray Hilborn (University of Washington, USA) – discusses the potential environmental and biodiversity impacts of shifting global animal protein sources from marine capture fisheries to terrestrial agriculture, reporting that such a replacement, often promoted in discussions on sustainable food systems, could actually accelerate biodiversity loss due to agriculture’s more profound ecosystem disruptions compared to well-managed fisheries.

“Tradeoffs are increasingly important in food production decisions as nothing is perfect and making responsible tradeoffs requires good information. Protecting biodiversity is a key factor in responsible food production and simply shifting the impacts somewhere else is no longer a viable approach,” corresponding author Duncan Leadbitter told the Advocate. “Fortunately, well-managed fisheries have an advantage over agriculture in that they seek to work within natural ecosystem structures, not replace them. This doesn’t mean that there can, or should be, zero impacts but weighing up the consequences of decisions helps design ways of seeking a balanced approach.”

This research provides a critical examination of the biodiversity trade-offs of substituting marine capture fisheries-derived animal protein with terrestrial agricultural sources, and challenge prevailing narratives which portray fishing as highly destructive while advocating for land-based alternatives. Instead, the authors argue that such a shift, under current dietary and production patterns, would likely amplify biodiversity loss, as agriculture converts complex natural ecosystems into simplified human-dominated landscapes, whereas well-managed fisheries operate within existing ecosystem structures.

The authors contextualize sustainability debates in food systems, noting that global population growth and rising wealth elevate human trophic levels and drive land conversion for food production, noting that half of the planet’s habitable land is now used for agriculture, with 77 percent dedicated to animal production, including feed crops, and emphasizing biodiversity as a key metric, highlighting understudied comparative impacts between food sectors.

The key sections of this study compare mechanisms of biodiversity impact, with agriculture activities reportedly driving loss through habitat clearance, particularly in tropical forests where more than 80 percent of expansion since the 1970s has occurred, leading to homogenization and species decline. Conversely, fisheries primarily affect higher trophic levels via removals and bycatch but maintain foundational productivity like primary productivity through the phytoplankton. Destructive practices like bottom trawling have localized effects, often recoverable, unlike irreversible deforestation.

Using quantitative analyses can help quantify land demands: replacing the animal protein from ~80 million tons of annual marine capture fisheries with the current livestock mix would require an additional ~5 million square kilometers of land – larger than intact Brazilian rainforests. Alternatives like grains or soy would need ~481,390 square kilometers and ~230,230 square kilometers, respectively, still risking habitat conversion. For aquaculture, substituting fishmeal with terrestrial agricultural meals could demand over 47,453 square kilometers of new cropland. Extinction risks underscore this difference: data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) show agriculture threatens 22,728 Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable species – over 10 times the 2,143 species affected by fishing. And per million tons of protein, risks are 2.6 times higher for agriculture, with agriculture also indirectly impacting aquatic species via runoff and dams.

Overall, the conclusions of this research caution that restricting fisheries without trade-off analysis may worsen biodiversity outcomes, advocating improved tools like enhanced Life Cycle Assessments and sustainable fisheries management to rebuild stocks.

For the fisheries, aquaculture, agriculture, and marine ingredients sectors, the findings of this study are pivotal. For capture fisheries and organizations like The Marine Fisheries Organisation (IFFO), the evidence counters anti-fishing rhetoric, positioning well-managed wild-catch as biodiversity-favorable compared to land expansion. And they support advocacy for management enhancements that have enabled stock recoveries, potentially adding 16 million tons of sustainable catch.

Aquaculture stakeholders must address the more than 47,000 square kilometers land estimate for soy-based feed substitution, highlighting risks in reducing fishmeal reliance. This drives innovation in alternatives like microbial or insect proteins to grow without terrestrial trade-offs. And agriculture faces intensified scrutiny for dominating habitat loss, with expansion exacerbating tropical deforestation and regulatory pressures on several commodities, with the argument made that the sector should prioritize efficiency and regenerative practices to mitigate biodiversity risks.

Overall, the research encourages cross-industry collaboration for integrated food systems, balancing marine and land sources to meet demand while minimizing extinctions. The authors promote realistic strategies: change diets toward plants to reduce livestock impacts, influence sustainable fisheries to spare land, and develop transparent tools for localized comparisons – promoting and supporting resilience amid climate and population pressures.

“The ultimate drivers of the increasingly tough decisions about the future of the world’s species and habitats are related to the increasing numbers of people and their growing wealth, and importantly overconsumption by the wealthiest nations. Policymakers require information on the consequences of decisions to substitute one source of food for another in order to avoid a leap from the frying pan into the fire,” conclude the authors.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Darryl Jory, Ph.D.

Editor Emeritus

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,121,114,111,106,46,108,121,114,114,97,100]

Related Posts

Responsibility

A circular economy approach to transform the future of marine aquaculture

Marine microalgae-based aquaculture has the potential to provide greater than 100 percent of global protein demand by 2050.

Fisheries

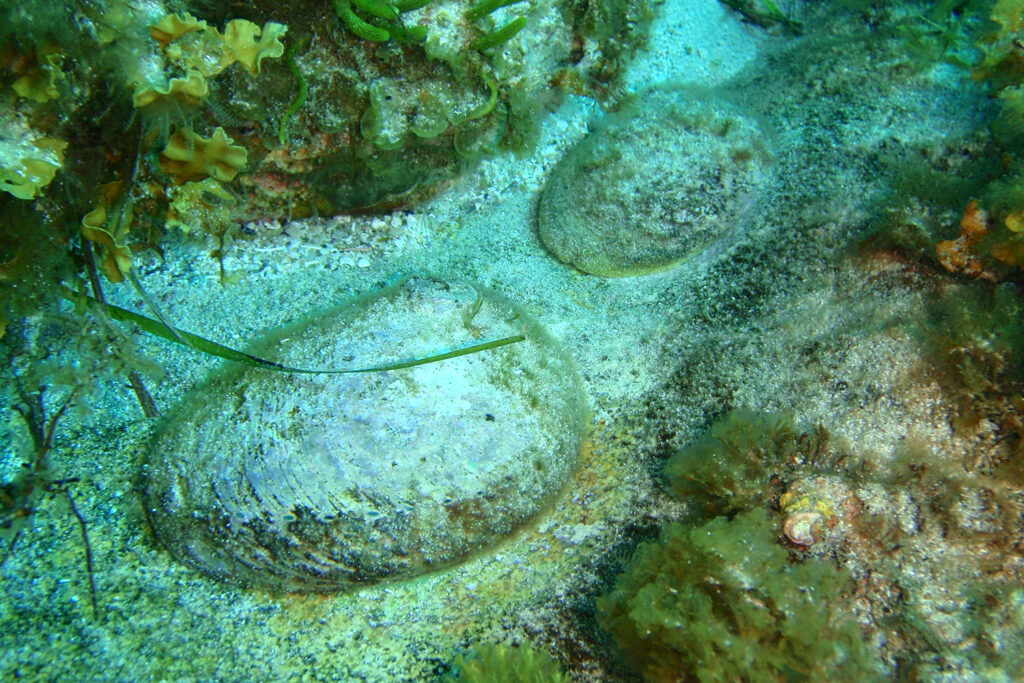

A global IUCN Red List assessment of abalones at risk in a changing climate

Abalone are vulnerable to climate stressors and require restoration aquaculture, reductions in fishing pressure, MPAs and other measures.

Intelligence

‘Through science, there’s no question’: How evidence-based transparency is changing seafood traceability

ORIVO, a science-based testing and certification service for the global feed and supplement industry, aims to change seafood traceability.

Fisheries

‘Who will win and who will lose?’ How climate change is shifting the ocean food chain – and potentially global fisheries

Climate change is shifting the foundation of the ocean food chain, potentially but not definitively causing a poleward migration of fisheries.

![Ad for [membership]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/membership_web2025_1050x125.gif)