University of Plymouth researcher sees fish populations migrating, costs rising and a greater need for rewilding through regenerative aquaculture

Seven months after global leaders gathered in Nice, France, to rally behind ocean protection, most of the promises remain on paper – yet the ocean’s future is still murky. The 2025 UN Ocean Conference produced bold pledges to protect biodiversity, regulate the high seas and funnel billions into ocean conservation and science. But momentum on stage has yet to reach the water. Less than 3 percent of the ocean is fully protected. Enforcement is inconsistent and funding remains short.

Meanwhile, the ocean is changing, with scientists warning that marine ecosystems may soon become “unrecognizable.” A study published last May, around the time of the UN summit, underscores that concern: It found that more than 21 percent of the global ocean, including vast coastal and open ocean regions, has become darker in the past two decades.

“There has been research showing how the surface of the ocean has changed color over the last 20 years, potentially as a result of changes in plankton communities,” said Dr. Thomas Davies, the study’s co-author and associate professor of marine conservation at the University of Plymouth. “But our results provide evidence that such changes cause widespread darkening that reduces the amount of ocean available for animals that rely on the sun and the moon for their survival and reproduction.”

That’s not just bad news for biodiversity. As this vital zone shrinks, it could disrupt fish behavior, shift plankton dynamics and destabilize food chains. For the seafood industry, it’s more than an ecological red flag – it’s a looming business risk.

‘Stuff in the sea’

It’s not just plastic pollution or oil spills that destabilize the ocean. Sometimes, the problem is light.

“Ocean darkening is basically changes in the optical properties of the water – or stuff in the sea,” Davies said. “When you make a cup of tea, you pour in hot water and stir the tea bag. You’ll see the tea gradually darken. It’s the same in the ocean.”

Those particles scatter light, while dissolved organic compounds – like the tannins that tint your tea – change the water’s color. Add in nutrients that supercharge plankton blooms, which absorb even more light, and you get a recipe for dimming seas.

“All this stuff – physical, chemical, biological – is increasing,” Davies said. “And as a consequence, light is not penetrating as far into the oceans as it was 20 years ago.”

What causes oceans to get darker, Davies speculated, is complicated but likely connected to what happens on land.

“Increased rainfall and melting glaciers as a result of climate change mean there’s more stuff being washed down,” he said. “We’re also seeing changes in land use, such as deforestation. And with intensified agriculture, there’s the application of stuff to the land, like fertilizers, which then washes off and stimulates plankton growth.”

Beyond that, other forces are at work. Changes in ocean temperatures and circulation appear to be altering plankton dynamics in ways scientists are only beginning to understand.

“What we think is happening is that changes in ocean circulation patterns are causing regions of the ocean where deep water upwelling occurs to increase, intensify or shift,” Davies said. “That’s stimulating plankton growth at the surface, and on net, we’re seeing more darkening.”

‘Alarm is necessary’

When scientists talk about a “darkening ocean,” they’re describing more than a color change. It’s also a physical transformation. At the center of that shift is the photic zone – the light-filled layer of the ocean where about 90 percent of marine life lives – which has grown shallower.

“It’s the bit of the ocean that sustains all our fisheries and everything else,” Davies said. “If that zone – the thickness of that zone, its depth – is reducing, then that’s a major form of habitat loss. It implies there’s less space for things to happen.”

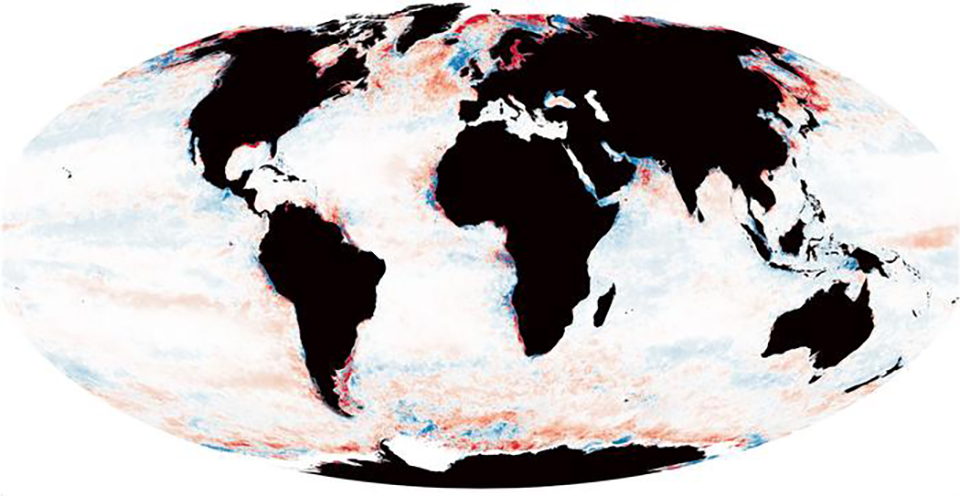

To understand the scale of that loss, the research team turned to satellites. Using NASA’s Ocean Color Web, which divides the global ocean into 9-kilometer pixels, scientists tracked annual changes in the depth of photic zones around the world. Combined with solar and lunar light models, the data revealed a stark pattern.

Roughly 9 percent of the global ocean – an area about the size of Africa – has seen its photic zone shrink by 50 meters or more over the past two decades. That’s a massive volume of water where biologically useful light no longer reaches.

“We rely on the ocean and its photic zones for the air we breathe, the fish we eat, our ability to fight climate change and for the general health and well-being of the planet,” said Davies. “Taking all of that into account, our findings represent genuine cause for concern.”

Not all parts of the ocean are getting darker. About 10 percent of the ocean has actually lightened over the same period – more than 37 million square kilometers. Clearer waters have been observed off the west coast of the United Kingdom, stretching out from Northern Ireland. But move farther north toward Iceland and into the open Atlantic and the picture changes. Vast areas are growing darker.

“It depends where you look,” Davies said. “It’s quite a spatially dynamic picture.”

Still, the ocean is losing light, and the scale of change is alarming.

“I struggled with these results when they first appeared on my computer,” said Davies. “On the one hand, the numbers are frightening. On the other, reporting them seemed a bit ‘hand wavy.’ But I concluded that at this scale of change, alarm is necessary.”

‘Where have all the fish gone?’

From a biological perspective, ocean darkening functions much like habitat loss. As light-dependent space shrinks, marine life is compressed into a thinner layer of water. That compression has consequences for how ecosystems function.

“If you have less light penetrating as far, stuff in the ocean is less able to live out its life,” Davies said, adding that in a murkier environment, organisms must expend more energy to find food, locate mates and avoid predators. “If I’m driving on a very foggy day, I have to slow down, put my fog lights on and concentrate. The same is true when you create a murkier, more opaque and darker marine environment.”

Many species partition the water column by depth, responding closely to light. Zooplankton, for example, migrate downward during the day to avoid predators and rise to the surface at night to feed. As light penetrates less deeply, those migrations compress upward, increasing exposure and competition – a process Davies calls a “pelagic squeeze.”

“The volume of water for biological processes to happen is getting more and more reduced, and that is the habitat loss element,” he said. “That creates more competition for space and resources, and it increases vulnerability to predation.”

What that ultimately means for global fisheries remains uncertain. Davies is careful not to overstate the evidence.

“In terms of fisheries, I think it certainly has the capacity to limit harvests,” he said. “But we need more empirical evidence of that.”

What is already known, however, is that fish are likely to move.

“It’s very clear from the maps that the oceans are changing,” Davies said. “And where stuff goes is also going to change.”

Even if overall biomass remains stable, shifting distributions could reshape fishing patterns, fuel use and long-term planning.

“It would certainly impact where fishermen would need to go to access those resources,” Davies said. “There’s also just not knowing, ‘Where have all the fish gone?’ Well, they’ve gone over there. But you don’t know it.”

In coastal waters, darker conditions often coincide with lower biodiversity, particularly near human development. Even where productivity increases, those gains may be offset if marine life struggles to feed and function efficiently in low-light environments.

“I think there’s a very good chance that it will have quite a profound impact on marine biodiversity at a local level,” Davies said.

The impacts, Davies acknowledged, are “several leaps of logic” that go beyond what has been empirically proven. More research is needed, and some will happen through a new Joint Action on Changing Marine Lightscapes initiative that kicked off last July.

“There’s good, sound ecological reasoning that underpins these ideas,” he said. “But no empirical evaluation yet. That all needs to be done.”

All clams on deck: How restorative aquaculture can repair Florida estuaries

A path forward – and a role for restorative aquaculture

For all the uncertainty surrounding ocean darkening, one thing is evident: Many of the most effective solutions start close to shore. Unlike the open ocean, where change is driven largely by climate forces beyond direct control, coastal waters sit at the intersection of land, sea and management – and are far more responsive to intervention.

“I think there are lots of things that we can do with regards to the coastal part of the problem,” he said. “A lot of this comes down to the way that we manage land.”

Reducing runoff through reforestation, shifting away from fertilizer-intensive agriculture, improving wastewater treatment and restoring wetlands can all reduce the flow of sediments and nutrients into coastal waters.

But some of the most promising solutions are already in the water. “There are nature restoration approaches which involve restoring habitats that once acted as natural filters,” Davies said. “That includes large-scale habitats made up of filter feeders.”

He points to oyster restoration projects in the North Sea as a powerful example. “Many centuries ago, we used to have extensive oyster beds,” he said. “That was all fished out. Now the North Sea is brown and murky. If you reintroduce those beds, they act as natural water purifiers.”

That combination – environmental restoration paired with production – is what makes restorative aquaculture especially compelling. “I think restorative aquaculture is a massive part of the solution,” Davies said. “Especially in our coastal zones, where oyster beds and mussel beds are gone.”

When paired with reduced seabed disturbance, the benefits can compound. Closures of scallop dredging near the U.K.’s Lyme Bay, Davies noted, have demonstrated how quickly bottom ecosystems can recover.

“A combination of reducing mechanical damage and restoring native aquaculture species could be really valuable,” he said. “For improving environmental quality and generating economic revenue.”

Scaling those efforts remains an upward battle. While government funding is often available, many restoration projects struggle to become commercially viable. “The problem is a lot of these ventures are not self-sustaining profitable ventures,” Davies said. “But they’re worth subsidizing.”

‘Hope on the horizon’

For Davies, the challenge isn’t a lack of solutions. It’s a lack of coordination.

“You cannot manage coastal marine ecosystems if you are not managing processes on land,” he said. “What you do on land impacts the sea.”

Too often, he said, decisions made upstream – from land-use change to large-scale industrial development – are assessed in isolation, without accounting for downstream consequences. Rivers, coasts and the industries that depend on healthy marine ecosystems are treated as separate systems when in reality they are tightly linked.

“That kind of joined-up thinking doesn’t really exist,” Davies said. “And it’s what’s needed.”

Davies remains optimistic, choosing to believe there’s “hope on the horizon.” Marine ecosystems, he added, are more resilient than they’re often given credit for – particularly in coastal zones where intervention is still possible.

“Marine ecosystems are very dynamic and very resilient,” Davies said. “These trends are certainly very reversible in our coastal zones, which is where it’s most important to reverse them.”

He often ends conversations with his students using the same ray of light.

“I always say to my students that I’ve spent most of my career documenting how mankind is damaging marine ecosystems,” said Davies. “But I hope that you spend most of your career documenting how mankind has helped them recover.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lisa Jackson

Lisa Jackson is a writer based in Hamilton, Canada, who covers a range of food, finance, and environmental issues. Her work has been featured in Al Jazeera News, The Globe & Mail and The Toronto Star.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Eye in the sky: Europe employs satellites to advance aquaculture

Copernicus – the European Space Agency’s €4.3 billion Earth Observation System – holds potential benefits for fisheries and aquaculture. The SAFI project is approaching the aquaculture sector about harnessing, and montetizing, this unique service from up above.

Responsibility

How restorative aquaculture is lending a helping hand to declining fish species

Researchers explore how effectively restorative aquaculture can enhance declining fisheries and safeguard native fish populations.

Innovation & Investment

‘We have 15 years to fix this planet’: Blue Food Innovation Summit explores potential of restorative aquaculture – and the challenges to scaling

At the Blue Food Innovation Summit, discussions centered on restorative aquaculture’s potential and financing the ocean’s capabilities.

Responsibility

The Nature Conservancy defines restorative aquaculture in new study

The Nature Conservancy's latest study sets out a standard definition of and global principles for restorative aquaculture.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)