New research shows that more than 100,000 people die annually across the global fishing sector, more than previously estimated

When thinking of the world’s most dangerous jobs, professions like construction worker, police officer and firefighter may be the first to mind. But studies indicate that commercial fishing is high on the list, and has been for a while.

The safety of fishers has been an “enduring problem” for the wild-capture seafood industry for many years. In the past, research by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1999 and subsequently by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has estimated that annual fisher deaths ranged between 24,000 and 32,000 respectively, a rate equaling 65 to 87 deaths per day.

However, a recent study by the FISH Safety Foundation (FSF), commissioned by The Pew Charitable Trusts, suggests that the problem far exceeds those estimates. By reviewing publicly available data and by cross-referencing it with investigative journalism and news articles, social media and private communications with government officials and others, the study authors say their work provides the most complete picture to date of the number of fishing-related fatalities worldwide.

Their findings suggest that more than 100,000 fishing-related deaths occur each year – three to four times greater than previous estimates. That’s a rate of 300 fisher deaths each day, and remarkably, this could be an underestimate given that deaths often go officially unreported and unrecorded.

“It has been widely speculated that fisher mortality estimates have undercounted and hidden the danger of fishing,” said Eric Holliday, chief executive of FSF. “Our analysis is the first of its kind and conclusively shows that a lack of transparency in the fishing industry endangers lives by obscuring the full picture of what occurs on vessels or at fishing grounds, making it difficult for governments to set effective policies to improve safety.”

Aside from fisher mortality estimates, serious injuries and abuses, including child labor and decompression sickness (e.g., from workers being forced to make repeated deep dives to harvest lobster), are also well-documented across the sector.

But what exactly is driving the danger? And how can safer occupational environments be created so that the seafood industry can continue to grow and thrive?

Uncovering the root causes

When it comes to naming and blaming, the study points to “insufficient and unenforced safety regulations” as a key challenge, but also other overlapping factors that “lead individuals to risk their lives and die on the water.” These include:

- Geopolitical conflict

- Overfishing

- Climate change

- Scarcity of fish due to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (or IUU fishing)

- Desperation caused by poverty and food insecurity challenges driving fishers into IUU fishing practices

Regarding those most at risk, the study findings indicate that these deaths and injuries disproportionately affect impoverished people (including children) in low-income countries, which is a major reason they are not always officially reported and recorded.

According to FAO, more than 3 billion people rely on fish and other marine species as a significant source of protein – and experts predict that number to increase in the future. Without action, that could increase occupational risk.

“While fishing can be inherently risky, the harsh reality is that many of these deaths were and are avoidable,” said Peter Horn, a project director with Pew’s international fisheries project, which is focused on ending and preventing illegal fishing. “With 3 billion people reliant on seafood and the demand expected to rise, stronger policies are urgently needed to keep fishers safe, including ones that address the true drivers of these deaths.”

Can a data-sharing tool eliminate IUU fishing and make seafood supply chains more reliable?

IUU fishing ‘a significant driver’

The study identified IUU fishing as “a significant driver” of fishing hazards, particularly as the demand for fish protein increases globally. FAO reports that one-third of all fish stocks are overfished and that another nearly 60 percent cannot sustain any increases in fishing. Stocks can become depleted due to insufficient fishing management measures or lack of rules enforcement.

The scarcity of fish due to poor management or the effects of climate change can compel formerly independent fishers to work on illegal boats where the operators may engage in dangerous behavior, such as fishing without safety equipment or radio communications devices or no limits on how many hours someone can work without sleep. It can also force poorly equipped boats farther out to sea for longer periods.

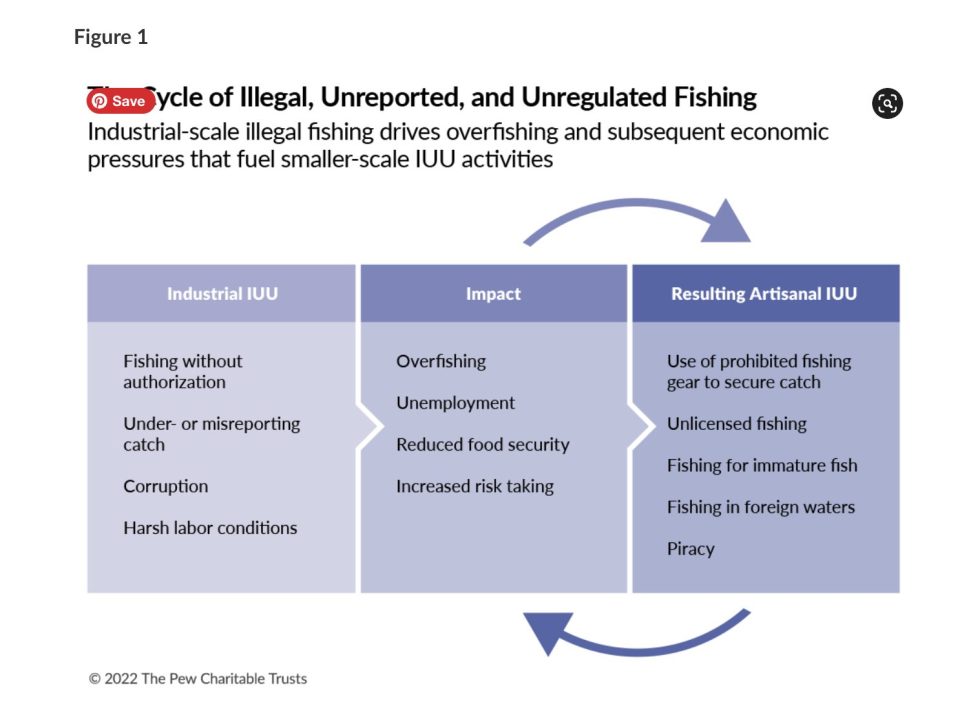

“Industrial illegal operators cut corners and ignore safety rules while contributing to the overexploitation of highly profitable catch,” The Pew Charitable Trusts stated in a press release. “This in turn drives what has been identified as ‘IUU by necessity,’ in which small-scale, artisanal fishers are driven to break rules or take part in unregulated, dangerous activities as it becomes more difficult to find fish. These conditions are exacerbated by climate change and the changing distribution of fish stocks.”

It’s a vicious cycle: Increased IUU fishing can lead to catch exceeding science-based catch limits, which can then result in further depletion of the stock.

“All these factors, in turn, increase human mortality rates, particularly for vulnerable people and communities,” wrote the organization. “The overfishing-IUU-fisher mortality cycle will continue until international and national authorities address IUU fishing at each level and set catch limits that prevent overfishing.”

‘A wake-up call’ to action

This complex conundrum cannot be solved with a single solution. For example, in its study, FSF pointed to three interrelated categories of IUU fishing that can contribute to fisher deaths:

- Organized industrial IUU fishing: Typically undertaken by distant fleets using larger vessels seeking to exploit highly profitable catch, such as tunas or sharks. Although various U.N. organizations and other maritime and fishery oversight bodies have rules that govern vessel safety in international waters, organized illegal operators disregard these measures, fishing in marginal conditions and putting crews at risk.

- Organized small-scale IUU fishing: Organized fisheries crime also occurs in small-scale and artisanal fisheries. In these cases, fishers often operate within larger networks of illegal traders, some with organized crime or piracy groups, or people knowingly transshipping catch from illegally operating industrial vessels or using bribery and other forms of corruption to siphon revenue from officials.

- IUU fishing by necessity: This category is one of the largest contributors to fisher mortality. In small-scale fisheries, millions of people rely on catch for food and livelihoods. And in all regions of the world, from southeast Asia to inland Africa, individuals engage in IUU fishing because they have no alternatives. Poverty, the need for nutrition, climate change, geopolitical conflicts and overfishing are the leading causes of these activities.

Because the drivers for each type of IUU fishing are so different, each needs a distinct solution. For example, addressing the factors behind artisanal IUU fishing will require a different approach than large-scale illegal fishing. For the former, governments and other fishery management bodies would need to develop equitable solutions, including localized financial support and capacity building for governments and artisanal fishers. On the flip side, industrial IUU fishing calls for more aggressive, large-scale solutions, such as regional or global policy and enforcement efforts.

In digesting the findings, The Pew Charitable Trusts has urged action on multiple fronts. The organization said that more action is needed domestically to implement fisher safety measures and address key drivers. Given the disproportionate levels of fatality in low-income communities, financial support and capacity building need to be ramped up.

However, there is one across-the-board measure that could lead to improved fisher safety: Better data collection. To improve accountability of their fishing fleets, the FSH and The Pew Charitable Trusts recommend that governments and regional fisheries management organizations improve recordkeeping and reporting of fisher deaths and injuries.

“The FAO, IMO and ILO have a role in protecting the sector’s workforce,” said the organization in an issue brief. “This oversight includes finally ensuring transparent reporting and information sharing on fisher deaths and injuries and establishing an accessible and universal repository for fisher safety data that all countries can contribute to equally. This effort would provide critical data necessary for governments to better target their policies and practices to protect people and communities.”

The FAO recently called for the creation of a mechanism to record and reduce fisher mortality, with support from the seafood industry and non-government organizations worldwide.

“While we may never be able to pinpoint an exact number of fisher deaths, this [study] should serve as a wake-up call to governments, telling them that in order to save lives, urgent action – informed by better reporting and sharing of mortality data – is needed,” said Holliday.

Read the case studies and full report.

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lisa Jackson

Associate Editor Lisa Jackson is a writer who lives on the lands of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations in Dish with One Spoon territory and covers a range of food and environmental issues. Her work has been featured in Al Jazeera News, The Globe & Mail and The Toronto Star.

Related Posts

Fisheries

Global fight against IUU fishing reaches a ‘new milestone’ with Port State Measures Agreement

One hundred States endorse FAO Agreement on Port State Measures, marking a new milestone in the global fight against IUU fishing.

Fisheries

Canadian government combats IUU fishing with Operation North Pacific Guard

Operation North Pacific Guard, an annual international law enforcement operation in the North Pacific, aims to detect and deter IUU fishing.

Fisheries

Global analysis of where fishing vessel tracking devices are disabled provides insights into IUU fishing

A new dataset of intentional disabling of identification devices by fishing vessels provides new insights into IUU fishing activities.

Intelligence

‘Through science, there’s no question’: How evidence-based transparency is changing seafood traceability

ORIVO, a science-based testing and certification service for the global feed and supplement industry, aims to change seafood traceability.