Oysters and other shellfish can help complement land-based nutrient management practices, say UNH researchers

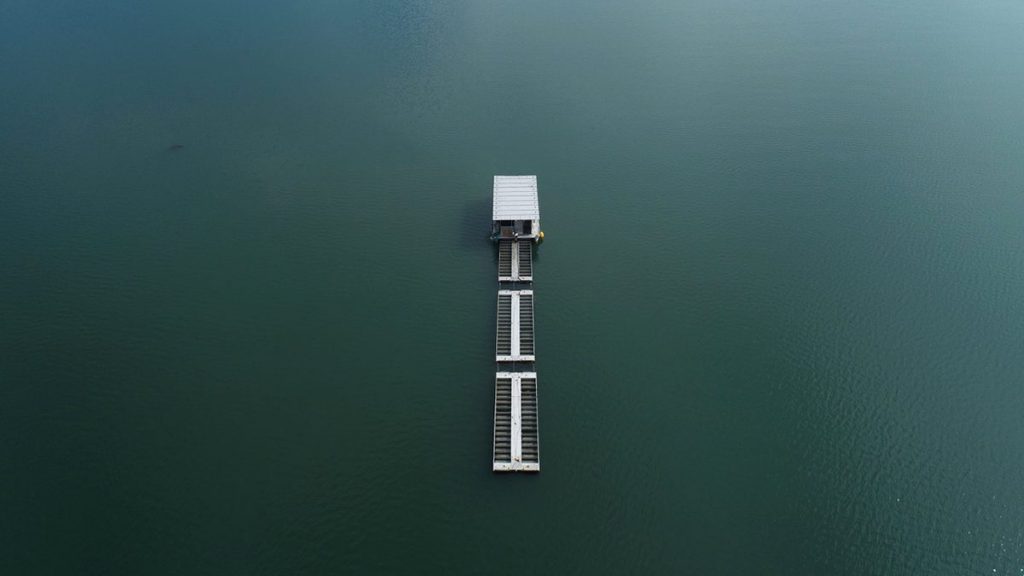

Researchers with the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station are exploring whether oysters can play a role in improving water quality in the Great Bay estuary.

More than 1,000 acres of wild oyster reefs once populated New Hampshire’s Great Bay Piscataqua River. However, 90 percent of those reefs have been lost over the past five decades due to pollution, overharvesting and disease.

The 2020 Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Great Bay Total Nitrogen General Permit was established to reduce excess nutrients, such as nitrogen, from flowing into the bay and causing eutrophication and algal blooms, as well as to support restoration efforts occurring throughout the estuary. The research team said that oysters could offer a “win-win” for nitrogen extraction.

“Whether the oysters are farmed or grow on wild reefs and then are harvested, they’re going through the same process of taking in organic nitrogen from particles in the water and sequestering that nitrogen in their shells and tissue,” said Ray Grizzle, a station scientist and research professor with University of New Hampshire’s biological sciences department. “In our 2016 paper, we determined that each oyster removes about two-tenths of a gram of nitrogen, and that they remove carbon from the system as well, once they’re harvested.”

In a 2020 study published in Estuaries and Coasts, scientists showed that oysters and other shellfish can help complement land-based nutrient management practices, such as upgrades to wastewater treatment plants around the Great Bay estuary to reduce nitrogen output. The research also found that while wild oysters cycle small amounts of that nitrogen back into the environment, farmed oysters, once harvested from the estuary, directly remove the nitrogen from the aquatic ecosystem. Such a combination of oyster farming and reef restoration efforts can maximize nitrogen reduction.

Ocean acidification isn’t just a carbon story – it’s also about nitrogen

Suzanne Bricker, the principal investigator of the 2020 study and the lead scientist for oyster ecosystem services with NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, estimates that nitrogen removal by existing Great Bay estuary oyster farms and reefs is 0.61 metric tons per year – and could be as high as 2.35 metric tons per year if aquaculture areas were expanded to the maximum suitable areas. An economic analysis conducted as part of the study estimates the value of the nitrogen removed by oysters was $105,000 per year and could be as much as $405,000 per year at current and expanded aquaculture levels.

“Bioextractive removal of nutrients by oyster aquaculture and reef restoration is an additional tool in our nutrient management toolbox that will contribute to the restoration of water quality in estuaries that support oyster populations,” said Bricker. “The results of this study by a multi-national team of ecologists, modelers, industry specialists and economists are very optimistic, confirming that oyster removal of nutrients is a win-win-win for needed domestic seafood production and jobs in rural areas, in addition to water quality improvement.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Responsible Seafood Advocate

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,114,111,116,105,100,101]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

This Maine company thinks kelp buoys and oyster farming can save the ocean through carbon capture and sequestration

Maine-based Running Tide uses carbon-capture and oyster farming techniques – using both low and high technology – to restore ocean health.

Responsibility

Climate change mitigation needs mariculture, new research concludes

NGO-academic collaborative study finds that mariculture “done right” can aid climate change mitigation by cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

Responsibility

As ocean acidification threatens the shellfish industry, this California oyster farm is raising oysters resistant to climate change

Despite the dangers to shellfish posed by ocean acidification, a forward-thinking California oyster farm is producing oysters resistant to climate change.

Responsibility

The Nature Conservancy defines restorative aquaculture in new study

The Nature Conservancy's latest study sets out a standard definition of and global principles for restorative aquaculture.