Opercule’s facilities are the first in Quebec to put water recirculation principles into practice

Located in an industrial basement is a two-person aquaculture operation that the Canadian province of Quebec hasn’t seen before. Opercule, an urban fish farm operating in northwest Montreal, has plans to produce around 30,000 kilograms of Arctic char per year, which it will sell and deliver directly to Montreal restaurant owners by electric bike.

Founded by Nicolas Paquin and David Dupaul-Chicoine, the two friends met at the École des Pêches et de l’Aquaculture du Québec before partnering to raise Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) that reuses 99.5 percent of its water. As the first recirculating urban fish farm in Quebec, it’s quickly making waves in Canada’s French-speaking province where the fish farming industry has had a harder time taking off.

“[The province is] really trying to push food sovereignty [… but] in Quebec, we produce 7 percent of the rainbow trout we consume,” said Dr. Grant Vandenberg, a professor at Quebec City’s Université Laval who specializes in aquaculture and fish nutrition. “It’s crazy.”

This low rate is in large part due to the aquaculture industry getting a bad name in the early 2000s, when a poorly maintained fish farm leaked phosphorus into a lake near Gatineau, Quebec, causing eutrophication.

Today, some 145 companies specialize in freshwater aquaculture in Quebec, mostly in the regions of Estrie, Chaudière-Appalaches, Bas-Saint-Laurent and the Laurentians, according to the Quebec Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food’s website. Marine aquaculture mainly consists of mollusk farming, with industry made up of about 20 active companies.

But for the aquaculture industry to move forward in Quebec, Vandenberg said that the provincial Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food needs to sit down with the Ministry of Environment to set the record straight about technologies and practices that have evolved safely in the last 20 years.

According to Vandenberg, for the aquaculture industry to move forward in Quebec, the provincial Ministry of Agriculture needs to sit down with the Ministry of Environment to set the record straight about technologies and practices that have evolved safely in the last 20 years.

“If you look at the profile of production in Quebec, through the 1980s and 1990s, it was going gangbusters and then, unfortunately, a couple of sites […] caused problems. Those places shut down, and new sites were essentially not approved or there was no increase in production,” said Vandenberg.

The Opercule team confirms that the thick red tape they encountered from both the provincial and municipal governments kept some of their ambitions in check.

“The permits were the main issue because it took so long, and we had to have this space [too]. You need to have the place where you’re going to do it, then ask for your permit,” said Paquin, explaining how the slightly backward legal process challenges both patience and finances. But with a high priority on green practices and a circular economy, the advent of Opercule could signal changing times. Could this urban fish farm help revolutionize the aquaculture industry in Quebec?

“Certainly, any effort to be able to break this cycle, which has been essentially a stalled industry development for the last 20 years, is a good thing,” said Vandenberg, who is currently working on a project to produce low-phosphorus fish feeds as he tries to move the industry forward.

The Opercule team sees how past mistakes in the industry continue to cast a shadow on evolved practices too: “The law has changed a lot, with the environment especially. At that time, I think effluents were just going directly into a lake, and that makes no sense because it just creates eutrophication,” said Dupaul-Chicoine, before Paquin illustrated how their urban location circumvents a lot of the issues that have stuck in the minds of legislators, adding “We use the city water and the city sewer as well.”

“There have been efforts to try and improve the [practice’s] environmental sustainability in Quebec farms, and they’ve done really good work, but the Ministry of Environment has done very little in terms of recognizing that and allowing for increased production in Quebec,” stated Vandenberg. In 2020, the province imported $550 million (U.S. $425 million) worth of fish and seafood, primarily from China, Chile, Vietnam and the United States. Among the provinces for which data is available, Quebec has the lowest aquaculture production in the country by a long shot, producing nearly four times less than Ontario, and 58 times less than British Columbia, meaning there’s a long way to go to attain self-sufficiency at our dinner tables.

Shaking up the Francophone fish scene

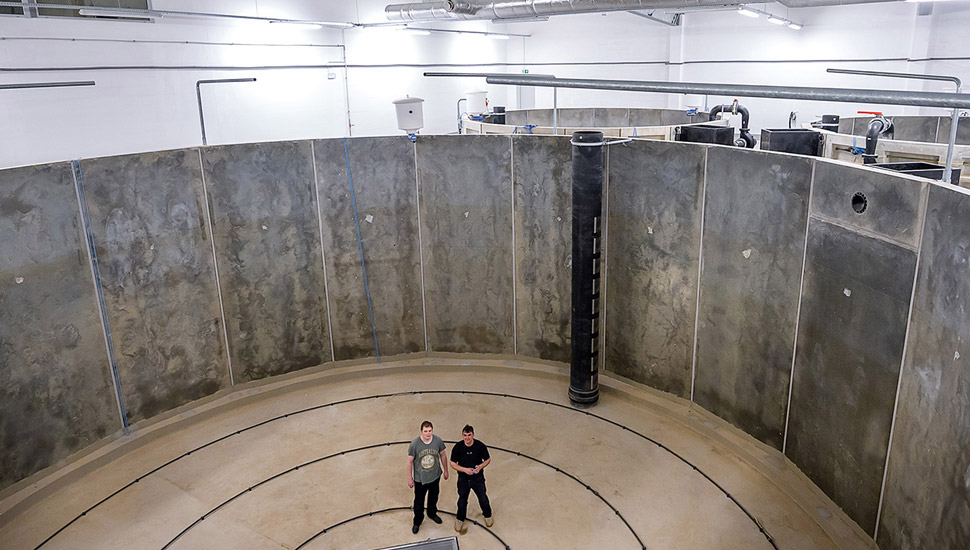

Opercule’s practices are an example of how aquaculture is changing in Quebec. Aside from the unique urban setup, the small farm’s facilities are the first in the province to put water recirculation principles into practice.

Paquin compares their system to a big aquarium: After being used in one of the farm’s seven tanks, the water goes through a mechanical filter that removes particles before being pushed through a biological filter that changes the ammonia into a less toxic version of this compound, called nitrite. Then comes a pass in a degasser to remove all the carbon dioxide (CO2), followed by a UV filter that sterilizes the water before running it through the ozone generator that neutralizes pathogens, at which point the water can be fed back into the loop.

RAS filtration also means it’s easier to use fish waste for fertilizer since it solidifies the material to make it easier to extract from the water. Dupaul-Chicoine had a longstanding personal interest in aquaponics, experimenting with the growing process at home in the past, and the duo is striving to make every step of their production as green as possible: from eggs to delivery. In the future, they hope that this method of production will eventually allow them to partner with another company and turn the waste from their fish cohorts into liquid fertilizer, destined for use at nearby urban vegetable farms.

Raising Arctic char in the approximately 35,000-fish operation was also a conscious decision. This species handles high density very well, and according to Dupaul-Chicoine, it’s with high numbers that they start acting like a school of fish. Otherwise, Arctic char can be territorial and aggressive towards each other.

With tanks clocking in at approximately 27 metric tons (MT), their basement location is a question of weight-related necessity. The spot does have its downsides to contend with: Though some natural light filters into the basement, lighting at the farm currently needs to be on around the clock until they can devise a dimmer system to mimic end-of-day sunset. Apparently, the fish become agitated when lights go out with the flip of a switch.

However, the advantages of an indoor, urban aquaculture farm are clear: Since Opercule has proximity to its eventual clients, the fish effluent can go straight into municipal sewers after being filtered so there’s no risk of contaminating other bodies of water. But RAS cuts their water usage dramatically when compared to traditional flow-through systems.

Vandenberg pointed out how this technology is a good match for the province’s hydroelectricity-centric power grid: “The advantage we have is we have the water, and we have relatively cheap electricity.”

Fish on wheels

On the economic front, given the small scale of their production, Opercule also opted for a fish species that would be lucrative and in step with the taste of Montreal’s restaurant industry, which is its main market. Arctic char is in high demand with local pillars of fine dining establishments, like Candide and Bouillon Bilk – two esteemed Montreal restaurants tested the farm’s products during the pilot project. Now, Opercule has a list of establishments waiting for the first cohort to reach the one to two pounds at which the fish is typically sold. The owners expect the cohort to hit this weight sometime around December 2022. At that point, their goal will be to provide an all-in-one service.

“We want to do delivery with electric bikes, [we can] prepare the fish and just deliver it, so it’s a real catch of the day,” said Paquin.

In prioritizing circular-economy principles, Opercule is also rethinking standards when it comes to what gets sold and what gets tossed in an ongoing effort to minimize waste. The company will be selling Arctic char that doesn’t meet standard weights as something they’ve come to call “chardines”: Little specimens that, with a little chef-fuelled creativity, can be eaten whole.

“The restaurant Candide made escabeche with them, using a vinegar-based broth. You can eat them as an appetizer, similar to smelt,” says Dupaul-Chicoine.

The company’s small scale, delivery methods and space mean they won’t be expanding beyond the city any time soon, though they are interested in having their products available at fish markets, and potentially selling direct to consumers via CSA baskets from members of the cooperative. Financed mainly through the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, and loans from the Canadian federal government and the Financière Agricole du Québec, they have a lot riding on this initial cohort – and it shows based on the level of care the team invests into the aquaculture operation.

“All the pumps are controlled automatically. We have cameras so we can watch them at home,” says Dupaul-Chicoine, sounding like a first-time parent. “Sometimes, I wake up at night to check on them.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Caitlin Stall-Paquet

Caitlin Stall-Paquet is a Montreal-based writer, editor, translator and occasional forest dweller. Her work has appeared in The Walrus, The Narwhal, the CBC, the Globe and Mail, Elle Canada, Canadian Geographic and enRoute.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Connecticut ‘urban fish farm’ leans on RAS to produce branzino

The Ideal Fish “urban fish farm” in Connecticut is producing branzino, or European sea bass, using RAS technology. Learn about this project from the company that designed and supported it: Pentair Aquatic Eco-Systems.

Intelligence

City fish-farm prototype set to prove itself in Minnesota

The Urban Organics model of farming leafy greens in conjunction with fish can work in any city environment, the company says. The first step is destroying East St. Paul’s image as a food desert.

Innovation & Investment

Polish RAS salmon farm mixes modern technology with ancient water

Jurassic Salmon, established in Poland just two years ago, is using 150-million-year-old geothermal saline waters from the “Lower Jura” era. Armed with certifications, the company is navigating an awkward growth stage.

Intelligence

Can aquaculture gain steam from geothermal energy?

China, Iceland and the United States are only just tapping into what could be a growing resource for seafood production: geothermal energy.