New study finds seaweed species may have different capabilities to remove nutrients from surroundings

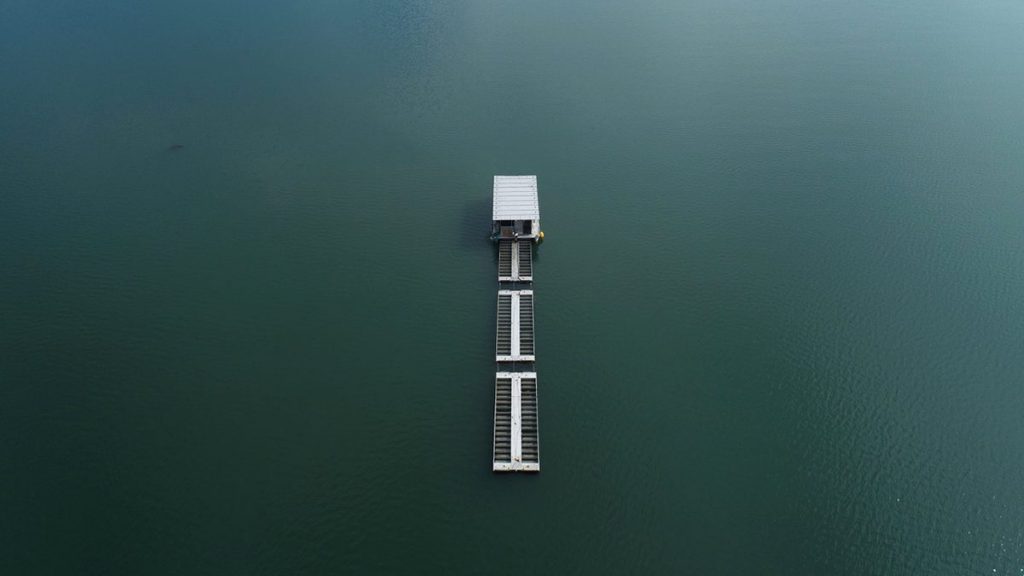

The water-filtering abilities of farmed kelp could help reduce marine pollution in coastal areas, according to a new study led by the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The paper, published in Aquaculture Journal, analyzed carbon and nitrogen levels at two mixed-species kelp farms in southcentral and southeast Alaska during the 2020-21 growing season. Tissue and seawater samples showed that seaweed species may have different capabilities to remove nutrients from their surroundings.

“Some seaweeds are literally like sponges – they suck and suck and never saturate,” said Schery Umanzor, an assistant professor at UAF’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences and the lead author of the study. “Although carbon and carbon sequestration by kelp received most of the attention, kelp is actually much better at mitigating excessive amounts of nitrogen than carbon.”

Nitrogen pollution is caused in coastal areas by factors such as urban sewage, domestic water runoff or fisheries waste disposal. It can lead to a variety of potential threats in marine environments, including toxic algae blooms, higher bacterial activity and depleted oxygen levels. Kelp grown in polluted waters shouldn’t be used for food but could still be a promising tool for cleaning such areas.

Kelp farming is an emerging industry in Alaska, touted to improve food security and create new job opportunities. It’s also been considered a global-scale method for storing carbon, which could be a way to reduce levels of atmospheric carbon that contribute to climate change.

Analysis of kelp tissue samples from the farms determined that ribbon kelp was more effective than sugar kelp at absorbing both nitrogen and carbon, although that difference was somewhat offset by the higher density of farmed sugar kelp forests.

Umanzor cautioned that the study was limited to two sites during a single growing season. She is currently processing a larger collection of samples collected from six Alaska kelp farms for the subsequent season.

“Maybe it’s a function of species, maybe it’s the site, maybe it’s the type of carbon and nitrogen out there,” Umanzor said. “There’s a lot to know in a follow-up study.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Responsible Seafood Advocate

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,114,111,116,105,100,101]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

This Maine company thinks kelp buoys and oyster farming can save the ocean through carbon capture and sequestration

Maine-based Running Tide uses carbon-capture and oyster farming techniques – using both low and high technology – to restore ocean health.

Intelligence

Digital tool aims to map kelp forest canopy and aid ecosystem restoration

U.S. scientists released KelpWatch.org – a digital map of kelp forest canopy that will be instrumental in ecosystem restoration.

Responsibility

Could cultivating kelp forests in salmon pens help ‘future-proof’ the sector?

KelpRing has received funding to explore the possible benefits of installing kelp forests within salmon pens to benefit cleaner fish.

Responsibility

Pilot project cultivating kelp on shellfish leases demonstrates ‘extraordinary’ first year growth

A pilot project led by the Aquaculture Association of Nova Scotia has shown first-year success for cultivating kelp on shellfish leases in Nova Scotia.