With increasing smoke, worsening water quality and fire-retardant drops, the effects of wildfires on the environment – and efforts to fight them – may cause harm to life under water

Wildfires are increasing in frequency and intensity due to global warming, with Climate Reality Project noting upticks in California, Brazil, Indonesia, Siberia and Australia. According to the U.S. National Interagency Fire Center, wildfires have burned more than 10 million acres twice in the last five years. That happened only once in the previous 33 years, in 2015.

Beyond the statistics, another indication that things have changed is that the term “fire season” has been replaced, according to Michelle Burnett, a spokesperson for the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service.

“We no longer talk about a ‘fire season’; we talk about a ‘fire year,’” she said. “Overgrown forests, a warming climate and a growing wildland-urban interface, after more than a century of rigorous fire suppression, has created a full-blown wildfire crisis.”

From an explosion of algae in oceans to mass fish die-offs, research and reports are emerging about how the effects of wildfires on the environment can alter marine ecosystems. With this reality, there’s growing concern that aquaculture and fisheries could be impacted, particularly through the effects of smoke, water quality changes or the retardants used to combat wildfires.

Where there’s smoke, there could be a fish kill

Wildfires lead to a massive amount of smoke, creating health problems for people hundreds of miles away. Wildfire smoke is a complex mix of particles, gases and pollutants that can burn eyes, irritate throats, cause headaches and harm lungs.

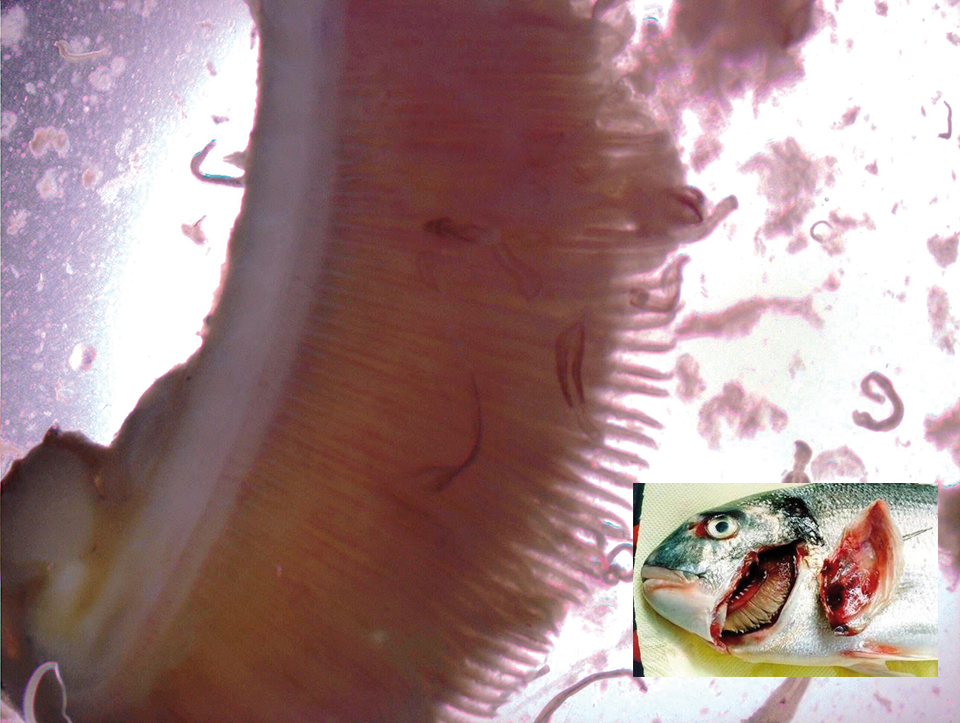

Fish do not breathe air but wildfire smoke can still make them collateral damage.

“One of the things we often see with a fire is a fish kill,” noted Mike Young, a research fisheries biologist with the U.S. Forest Service.

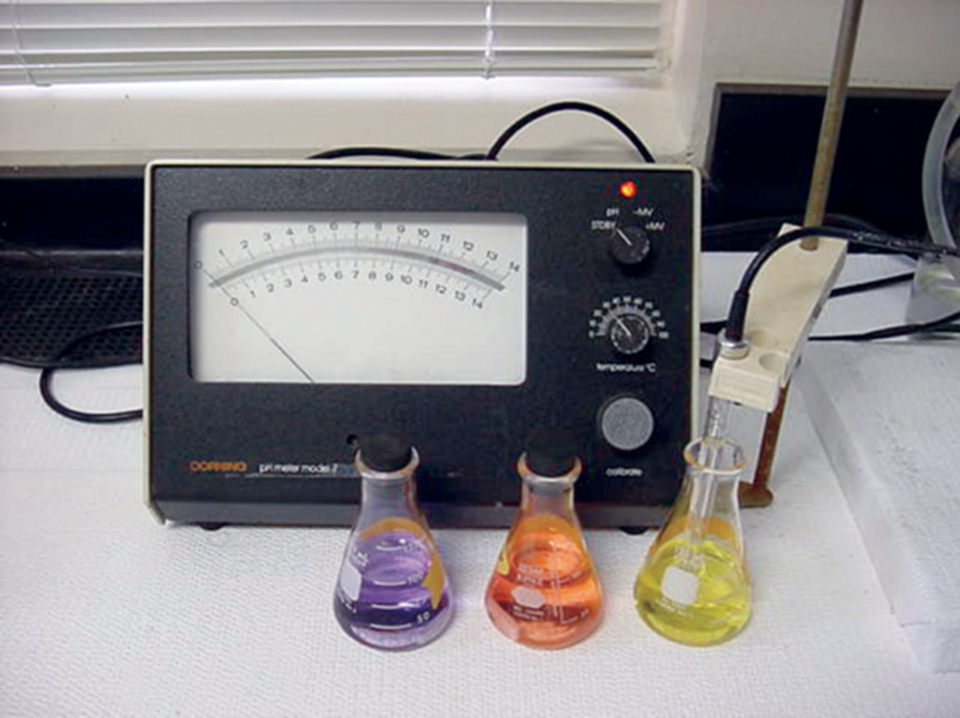

A common assumption is that the water gets too hot, but without evidence of temperature spikes as a result of wildfires, the leading theory now points to ash. Wildfire ash, Young explained, has an extremely high pH. When these very alkaline particles hit water, they tend to cause ammonia to appear.

“If you’ve got a fish tank, you know that ammonia is deadly. And it doesn’t matter what species they are,” said Young. “But it’s a really ephemeral effect. It has to happen under just the right circumstances.”

Researchers demonstrated this effect only once, as far as Young knows. But it is so short-lived that scientists making measurements on a body of water even a day later would find no signs of it. The water would seem normal, but the fish would be dead.

The smoke would have to be so thick that visibility would be zero, Young said. However, less dense smoke might stress fish without killing them. Regarding the long-term effects on fish, Young said that these vary by species, with some benefiting and others suffering.

Aquatic impacts can also show up at a distance. A 2020 study found that wildfire in Australia deposited nutrients in the ocean thousands of miles away, causing large algae blooms.

There’s something in the water

A second area of aquatic impact from a wildfire is in water quality. After a wildfire, vegetation is gone and there may be many downed trees and other debris. Later rains on the burn scar wash the debris away, impacting downstream surface water quality and any activity that depends on that water.

In California, for example, flash flooding after a wildfire caused a massive debris flow. In 2022, Biologists blamed the debris for thousands of dead fish downstream.

Putting out one fire, lighting up another?

A third issue to consider is how wildfire mitigation efforts can potentially affect aquaculture. For example, when not diluted by enough water, studies have shown that some fire retardants can be toxic to fish, a consequence of the ammonia within them. Even less than lethal concentrations can cause problems later.

For instance, a 2014 NOAA study found that a 96-hour exposure to various concentrations of widely used Phos-Chek fire retardants increased mortality when surviving salmon smolts entered seawater. The mortality hit disappeared if the fish had 34 or more days to recover. The study’s authors concluded that accidental airdrops during salmon outmigration would have adverse impacts that extend beyond the fish that die in the retardant drop and dilution area.

Asked about the use of fire-fighting chemicals, Burnett noted that the U.S. Forest Service is always seeking ways to make fire retardant as environmentally friendly as possible. She said the Forest Service tests all types of wildland fire chemicals for toxicity, finding that all fall into the Environmental Protection Agency’s “practically non-toxic” category for mammals, including people and aquatic species.

Retardant use varies by year, but Forest Service usage exceeded 50 million gallons in 2020 and 2021, up from the 30 million gallons used annually the previous decade. The agency is in the second year of evaluating a magnesium-chloride-based retardant, a formulation claimed by proponents to be more environmentally friendly than the ammonium-phosphate-based Phos-Chek.

The Forest Service keeps retardant aerial drops 300 or more feet away from waterways or avoidance areas mapped for threatened or sensitive species. Accidents do happen, though, and wildfires that put more lives and property in danger will cause choices that overrule these guidelines.

As Burnett said, “The only exception that allows aerial delivery of fire retardant into waterways and avoidance areas is when human life or public safety is threatened, and the use of aerially delivered fire retardant can reasonably be expected to alleviate that threat.”

With wildfires growing in severity, the chances increase for retardants entering waterways either accidentally or deliberately. Along with that possibility comes the proven adverse impact on water quality from debris flows and on marine life health from smoke. Combined, that’s a recipe that could prove a threat to aquaculture.

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Hank Hogan

Hank Hogan is a freelance writer based in California who covers science and technology. His work has appeared in publications ranging from Boy’s Life to New Scientist.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Chemical fertilizers in pond aquaculture

Chemical fertilizers are frequently used in pond aquaculture to stimulate phytoplankton productivity and enhance the availability of natural food organisms.

Aquafeeds

Microminerals are important feed components

Microminerals participate in a variety of biochemical processes and must be supplied in prepared diets to support optimal growth and production efficiency.

Responsibility

Pond bottom soil analyses

Limit pond soil analyses to soil particle size for use in pond construction decisions, initial analysis of total sulfur, occasional analyses of total nitrogen, and routine analyses of pH and soil organic carbon.

Responsibility

Correct liming improves pond water, bottom quality

Shrimp and fish farmers frequently apply liming materials to ponds to increase the pH of bottom soils, elevate alkalinity and water hardness and improve conditions for microbial activity and benthic animals.