Study synthesizes more than 100 billion GPS positions from 200,000 vessels to reveal patterns about vessel activity

A study led by Global Fishing Watch provides new insights into the global scope of potential IUU fishing (illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing) and could enable authorities to improve fisheries management and oversight.

The study, which was published in Science Advances, combines a decade’s worth of satellite vessel tracking data with identification information from more than 40 public registries to determine where and when vessels responsible for most of the world’s industrial fishing change their country of registration – a practice known as “reflagging.” The study also identified hotspots of potential unauthorized fishing and activity of foreign-owned vessels.

Using big data processing and a compilation of global datasets, researchers from Global Fishing Watch, the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab from Duke University and Stockholm Resilience Centre tracked and analyzed 35,000 commercial fishing and support vessels to reveal their changing identities and enable the reconstruction of vessel histories to demonstrate reflagging patterns.

The study found that close to 20 percent of high seas fishing is carried out by vessels that are either internationally unregulated or not publicly authorized, with large concentrations of these ships operating in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean and the western Indian Ocean.

“Until now, we’ve had limited information linking together the identity and activity of specific vessels,” said Jaeyoon Park, senior data scientist at Global Fishing Watch and lead author of the study. “When a vessel’s identity is changed, it makes tracking them all the more difficult, allowing bad actors the opportunity to take advantage of information gaps and avoid oversight. We need to close that loophole.”

Of the 116 States involved in reflagging, the study found that one-fifth of them were responsible for about 80 percent of this practice over the past decade, with most reflagging occurring in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Pacific Islands. The study found that reflagging takes place in just a few ports – Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Busan, Zhoushan and Kaohsiung have the highest activity. Vessels are often reflagged to States that are unrelated to the ports in which they are changing their registrations. This means that a vessel can change its flag from one country to another without ever having to enter port in either of those countries.

While there are legitimate reasons for a vessel to change its identity, abusive reflagging (or “flag hopping”) is one way that operators avoid oversight. The study found that fleets with prevalent reflagging are over five times more likely to be composed of vessels under foreign ownership, which are often registered to “flags of convenience” – countries that offer foreign shipowners the ability to register, or fly the flag, of their own State.

On the dark side: How technology helps to expose potential IUU fishing on the deep sea

While reflagging and foreign ownership are lawful, when not properly regulated and monitored, they can indicate a risk of IUU fishing.

“Knowing the identities of vessels fishing the high seas is critical for uncovering the connection between the potential IUU fishing behavior and vessels that repeatedly change their name, flag State or registered owner,” said Gabrielle Carmine, co-author and a doctoral candidate at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment. “This analysis could be used to help monitor fisheries more effectively and for accountability in the use and protection of marine biodiversity.”

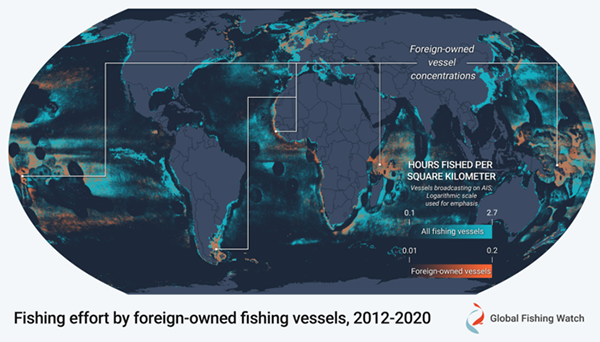

The study also identified concentrations of fishing activity by foreign-owned vessels, which are focused in parts of the high seas and certain national waters, including the southwest Pacific, the northwest Indian Ocean, Argentina and the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and West Africa, where vessels are typically owned by China, Chinese Taipei and Spain. The hotspots in this study correspond to the areas in which multiple non-governmental organizations have called for better governance systems.

“By synthesizing more than 100 billion GPS positions with consolidated identity information from 200,000 vessels, we were able to reveal patterns about vessel activity from the past decade,” added Park. “This study represents a major step forward in our ability to enhance monitoring efforts and help authorities direct enforcement resources.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Responsible Seafood Advocate

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,114,111,116,105,100,101]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

On the dark side: How technology helps to expose potential IUU fishing on the deep sea

To better monitor IUU fishing, watchdogs are turning to tracking devices, satellites and even artificial intelligence.

Fisheries

Study indicates that IUU fishing makes fishers’ jobs even more dangerous

Commercial fishing has long been one of the most dangerous jobs, and a new study suggests IUU fishing, overfishing and climate change are making it worse.

Fisheries

Global fight against IUU fishing reaches a ‘new milestone’ with Port State Measures Agreement

One hundred States endorse FAO Agreement on Port State Measures, marking a new milestone in the global fight against IUU fishing.

Fisheries

Global analysis of where fishing vessel tracking devices are disabled provides insights into IUU fishing

A new dataset of intentional disabling of identification devices by fishing vessels provides new insights into IUU fishing activities.