Planet Tracker’s new seafood database aims to improve transparency and steer the seafood sector to adopt greener practices

When it comes to behaving in an environmentally friendly way, not all companies are inclined to do the right thing. But what if you could provide data about their vulnerability to risk and use it to influence investors’ decisions? That’s the idea behind a new seafood database created by Planet Tracker – a nonprofit financial think tank that produces analytics and reports “to align capital markets with planetary boundaries.”

In December 2022, the UK-based organization released the seafood database, in which anyone can identify to what extent seafood companies are exposed to overfishing, illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing, and many other ocean sustainability risks, and compare a company’s environmental health with their financial health.

Planet Tracker’s goal is twofold: to avoid ecological collapse and to show how environmental data can be used to drive positive financial outcomes within the seafood industry.

“We actively want change, but our strategy is to engage in providing constructive data as opposed to judgment,” said Francois Mosnier, head of the oceans program. “Our role is almost an advisory one because we suggest to companies, ‘Here’s a different, better way of conducting your business that is also more profitable.’”

When Planet Tracker was founded in 2018, Mosnier and his team heard that seafood investors wanted to assess which seafood companies were operating in a responsible manner. However, the challenge was the dearth of sufficient data provided by those companies.

“We found that only a minority of companies disclose enough data publicly to allow for a sustainability assessment to be made,” he said. “For example, only eight out of 100 companies would tell us which exact species they catch, process or farm. Their answers can be very vague, making it impossible for an investor to understand the hidden risk.”

On a quest for greater transparency in the industry, Planet Tracker launched its Seafood Database with an analysis of 100 companies, the supply chains in which they’re involved and their respective species of focus. This data is overlaid with environmental considerations associated with those species and those regions, based on third-party data, and offers a risk or assessment score. By 2024, the database will include an analysis of up to 300 seafood companies.

Fish stock health is a prime example. Planet Tracker obtained data on fish stock health from Fish Source and overlaid that data with each company’s exposure to those fisheries.

Our goal is to provide that transparency so investors can form an opinion on a company’s impact on nature, and attribute capital accordingly.

“The score we provided allows the user to get an idea which companies are at most risk of overfishing, and which are dependent on stocks that are getting depleted,” he said.

Mosnier and his team were intent on learning about the financial materiality of overfishing and specifically if retailers were making more money selling overfished fish. They partnered with French retailer Carrefour to obtain a list of all the seafood Carrefour sold in France and examined the list for the sustainability of those species and how it compared with the margins made on those species.

“We found Carrefour made less money on overfished species than on species in good health,” he said. “So, our key message was that they needed to stop selling overfished seafood, because it’s not environmentally or economically viable. We want to change the idea that overfishing is profitable. If Carrefour stops selling an overfished species, it cuts all the suppliers selling those fish, and we reduce overfishing that way.”

Planet Tracker’s main audience is investors, but its research is available to anyone free of charge. According to Mosnier, anywhere from hundreds to thousands of investors have perused the material.

“The scientific research can be quite dry for an average reader, but we turn it into data on earnings risk that investors and chief financial officers would understand,” Mosnier said. “We know companies and investors are having conversations as a result of our reports and we have many examples of investors coming back to us and thanking us for making the data available.”

Illegal fishing is a tough challenge because it is unreported, but Planet Tracker wondered if it could at least help reduce the funding that goes to companies engaged in IUU fishing. It identified the key “red flags” that suggest which companies are potentially at high risk of engaging in IUU fishing and built an interactive tool that allows investors to conduct due diligence on the company.

“We have a list of simple questions that generates a risk score, and we’ve had 1,200 people using that tool,” he said. “While we don’t know what decisions investors have made as a result of that tool, if they spent the time to compute the score on a company, it’s likely that score at least partially influences their investment decision.”

The Seafood Database also encompasses wild fishing and aquaculture. Planet Tracker investigates the environmental issues for aquaculture companies and tries to see how they could be resolved using investors.

“We asked, what changes could investors ask companies to make? With our data, we’re encouraging investors to redirect capital outside of unsustainable aquaculture and into sustainable aquaculture that is not plagued by environmental issues,” he said. “For example, regenerative aquaculture like the culture of some seaweed and bivalves that can help restore habitat.”

If Planet Tracker’s Seafood Database has one central message, it’s that there’s value in providing transparency: “A seafood company might be doing all the right things, but simply not communicating about what they’re doing,” Mosnier said. “Our goal is to provide that transparency so investors can form an opinion on a company’s impact on nature, and attribute capital accordingly.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lauren Kramer

Vancouver-based correspondent Lauren Kramer has written about the seafood industry for nearly two decades.

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Through the tubes: Using pneumatic tubes to transport fish, this company’s fish passage is in demand

Whooshh Innovations uses pneumatic tubes to transport fish in wild and farmed environments, greatly reducing stress and improving product quality.

Health & Welfare

‘The right thing to do’: How aquaculture is innovating to reduce fish stress and improve animal welfare

With research showing that stress can damage meat quality, fish and shrimp farmers are weighing the latest animal welfare solutions.

Innovation & Investment

‘Plug-and-play’ shrimp farm inventor out to prove that Shrimpbox is more than just a neat idea

Is Atarraya’s AI-enabled, biofloc-based Shrimpbox, one of TIME Magazine’s top inventions of 2022, a game-changer for urban shrimp aquaculture?

Fisheries

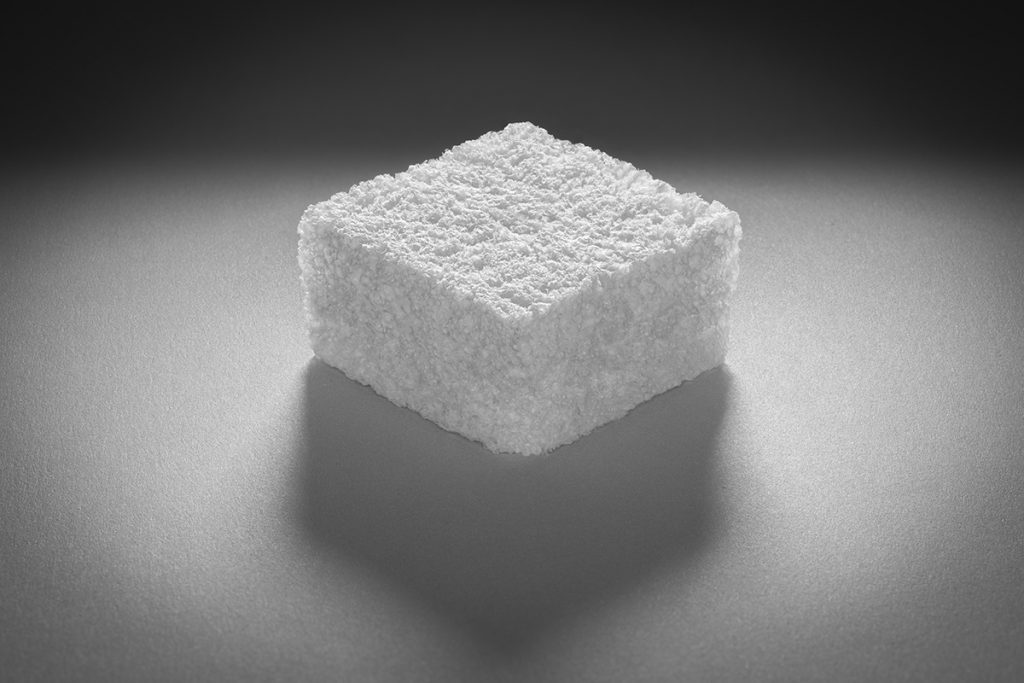

‘Regulation is pushing toward greenifying materials’: How one innovator is upcycling seafood waste into biodegradable packaging foam

GOAL 22: Cruz Foam’s biodegradable packaging foam made with shrimp shells is a finalist for GSA’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award.