Global Fisheries Innovation Award finalist: The North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group

Three years ago, the Northeast Atlantic mackerel fishery lost its Marine Stewardship Council certification. The stunning news sent fishermen, tinners and buyers into a form of limbo, simultaneously fearing the stock was in serious decline while also hoping to continue buying and selling the popular fish. Leading retailers were left wondering how to satisfy consumer demand and their sustainable sourcing policies, many of which held MSC certification as their compass.

What happened a few months later was a real eye-opener. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) conducted another stock assessment, and instead of finding the expected drastic plunge, it found that the fishery’s biomass – Northeast Atlantic (NEA) mackerel is a highly migratory and frequently fluctuating population – had in fact not dropped below the trigger point that would signal the loss of the certificate.

Yet the MSC certification remained suspended because of poor management, according to Dr. Tom Pickerell, head of Tomolamoa Consulting and a longtime fisheries-management expert. The reasons the fishery was failing in the eyes of the standard-holders and many other observers, he told the Advocate, were purely political. Like any international governing body, the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission, the official NEA mackerel fishery manager, was only as effective as its member states wanted it to be.

And the coastal states with claims on the mackerel fishery – Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, the European Union and the United Kingdom – had fallen into a “decade of deadlock,” Pickerell said, as quotas were being unilaterally set and not in adherence with ICES recommendations. Last year, Norway’s unilaterally set quota was 55 percent higher than the previous year; the Faroe Islands quickly retaliated with a similar increase. Any corrective actions to reinstate MSC certification were far beyond the direct authority of the fishery clients – the onus of repair was squarely on governments.

“It was like horse trading, every year,” Pickerell said. “There was no long-term management plan, no allocation agreement, no method for dispute resolution. And there was nothing fishers needed to do, so long as they were fishing legally.”

Market forces then took a stand. A collective of retailers and seafood supply chain businesses came together (supported by Seafish) and hired the former Seafish technical director to find a way forward. He suggested a Fishery Improvement Project, but as Pickerell explained, the FIP he envisioned was unique from most others, as it would focus on a fishery falling short, but not in a biological sense. This one, he said, would be the first purely political FIP, aimed at holding coastal state governments’ feet to the fire if their promises were not kept. The North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group (NAPA), officially launched in April 2021, has three main goals. Getting MSC certification reinstated is not (necessarily) one of them.

“That’s not our stated aim,” said Pickerell, the NAPA project lead. “First, an allocation measure must be agreed upon – this is everyone’s share of the pie, and ideally it would have to be redone every three to five years to account for any stock migration. Second, the scientific advice must be followed – this is the size of the pie. And third, [we need] implementation in a management framework so we don’t have to do this every year. It’s a building block of fishery management. We’re not interested in whose slice of the pie is bigger.”

The North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group (NAPA), is one of three finalists for the Global Seafood Alliance’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award, as determined by GSA’s Standard Oversights Committee. NAPA’s efforts entail the management reform of three commercially important species: Northeast Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus); Atlanto-scandian (Norwegian spring spawning) herring (Clupea harengus L); and Northeast Atlantic blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou), which is primarily turned into fishmeal and fish oil.

The winner of the Global Fisheries Innovation Award will be determined at GSA’s GOAL conference next month. All this month, the Advocate will feature the six finalists from both the fisheries and aquaculture categories.

‘Consequences of inaction’

The NAPA FIP, enacted in 2021, is set to run for three years. After which the three fisheries – Atlanto-scandian herring and blue whiting were added to the project because their stocks were “on a similar trajectory” as mackerel, said Pickerell, although each target species has varying associated coastal states involved in its capture – will either be considered a collective success or the marketplace partners will make good on a commitment to reassess their buying positions. Some have vowed to walk away if the NAPA FIP fails due to government inaction or to limit their sourcing to those nations fishing responsibly.

NAPA members – leading global retailers, seafood suppliers and aquafeed companies from across the region – have put their commitments in ink. Labeyrie Fine Foods, for example, a France-based company with more than €1.1 billion ($1.1 billion U.S.) in annual turnover, sources both mackerel and herring and stated that if the fisheries don’t meet the requirements of its sourcing policies and if coastal states can’t agree on the control mechanisms laid out by NAPA, it will re-evaluate sourcing choices “with a view to only select Coastal States championing sustainability that actively support NAPA.”

In its sourcing statement supporting NAPA, Young’s Seafood, the largest seafood processor in the UK, said that if mackerel catches continue to exceed the advice of ICES, it would “cease sourcing from these fisheries.”

Because of anti-trust regulations, NAPA cannot speak commercially on behalf of its members; the sourcing statements must be individual. That Young’s, Morrisons, Cargill, Skretting, Asda, Tesco, Nor-Sea, Princes Ltd., Waitrose, Aldi Group, Biomar, Thai Union, Ahold Delhaize, Woolworths (South Africa) and dozens of others have joined the effort speaks to what’s at stake, said Pickerell.

“They have to speak up and say what they will do. They need a good reason to stay,” he said. “What I want to see is them contacting their fisheries ministers and putting constant pressure on them,” he continued, noting that the commercial leverage being employed here is a powerful tool atypical of FIPs.

“There was no collaborative position before. Each company was effectively one voice in the wilderness. Our strategy is more about the consequences of inaction. Everyone’s bought into it. They’re still purchasing, with the security of a FIP. But if the FIP fails, we have to do something. It cannot be the status quo,” he said. “[Coastal states] have a three-year period to make a change. This could happen in one meeting – just do what you’ve all signed up to do with the SDGs [United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals]!”

While some FIPs have been criticized for lacking time-bound commitments and triggers for meaningful action, Pickerell said the initiatives overall are an effective tool. Real consequences for failing to deliver on the objectives is what sets the good ones apart.

“There are some that are demonstrably productive, and some that are never-ending. It’s the whole spectrum,” he said.

We’ve gone from new on the block to maybe the most important and influential stakeholder.

Racking up the wins

NAPA members – 54 companies and five trade bodies (representing processing and retail interests), which collectively represent the markets for 100 percent of the herring, 50 percent of the blue whiting and 12 percent of the mackerel total allowable catches (TACs) and an €802 million share in NEA pelagic purchasing – don’t have to wait until the FIP expires in 2024 to deem it a success. Last year represented a huge step forward in that coastal states were finally recognizing that the time for action was upon them, said Pickerell.

“They agreed to meet in early January. That was a big win,” he said. What makes the NEA mackerel allocations especially sensitive is the fact that countries like Greenland and Iceland never targeted the species until the 2000s, because the fish was never traditionally present in their respective fishing grounds.

But the mackerel migrated west earlier this century. Iceland, which had never had any commercial mackerel fishery of note prior to 2002, took in an average of 99,120 metric tons from 2002 to 2020; the haul in Greenland, which never commercially harvested mackerel before 2007, has averaged 11,927 metric tons since then, and 41,627 metric tons from 2017 to 2020. The mackerel stock has migrated back east, though, prompting the question by some stakeholders of whether Iceland and Greenland should continue to claim any part of the overall allocation.

The current vibe is more cease-fire than peace treaty. Last October, delegates for all coastal states involved in the mackerel fishery agreed to a total allowable catch (TAC) in 2022 of 794,920 metric tons, in line with ICES advice and 7 percent lower than the TAC agreed upon for 2021, according to the European Commission. They also said this last year but Pickerell noted that the eventual mackerel TAC in 2021 was, however, 42 percent above ICES recommendations; herring and blue whiting TACs were 39 percent and 30 percent above ICES recommendations, respectively.

Halfway through the FIP, Pickerell is optimistic of its eventual success, or at least more optimistic than when the process began.

“When we first started, none of the coastal states replied to our letters,” he said. “A couple of months later, through collective action, we had established NAPA as the ‘market voice’ for sustainable pelagic seafood. We’ve gone from new on the block to maybe the most important and influential stakeholder.”

Pickerell said NAPA’s novel approach to FIPs is easily replicable and that fisheries worldwide, like Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna, can “absolutely” follow these footprints to improvement.

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

James Wright

Editorial Manager

Global Seafood Alliance

Portsmouth, NH, USA[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,116,104,103,105,114,119,46,115,101,109,97,106]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Aquaculture could enhance Mediterranean Sea urchin fishery

Although researchers in several countries are working to enhance sea urchin fisheries or commercial production, the development of a major commercial industry has been restrained by the lack of cost-effective production technology.

Fisheries

Ocean seeding and blue corridors: Can these approaches effectively safeguard fisheries?

Can seeding the ocean with iron spur phytoplankton growth? Will protecting migration routes save fish stocks? Exploring new ways to safeguard fisheries.

Responsibility

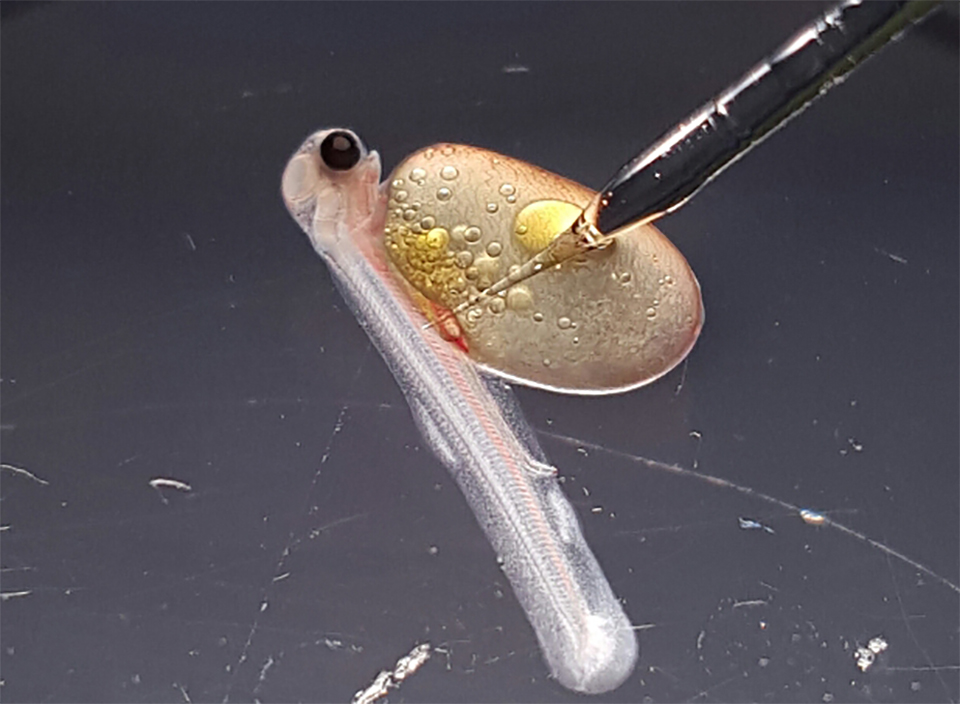

In Japan, aquaculture is deployed in the defense of endangered species

Tokyo University researchers have learned to spawn fish from germline stem cells in vitro, a method that can be deployed to help endangered species.

Intelligence

Seaspiracy film assails fishing and aquaculture sectors that seem ready for a good fight

Seaspiracy, a new Netflix documentary-style film, depicts the fishing and aquaculture in an ugly fashion but the industry response is swift.