Study establishes a morphological description of each individual krill maturity stage to identify and parameterize what determines size selectivity

The Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) fishery is a small-mesh pelagic trawl fishery managed by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, which in 1991 established a fixed precautionary catch limit to 620,000 tons (termed the ‘trigger level’) for the Southwest Atlantic sector. The trigger level was established due to limited available knowledge about the krill biomass, their distribution and population dynamics, predator needs and a lack of general Southern Ocean ecosystem knowledge. This trigger level has continued unchanged for this area and represents combined maximum historic catches with no basis in any assessment of krill biomass. The fishery cannot exceed the trigger level until there is evidence for this still being sustainable and that a mechanism is developed to distribute catches such that potential negative localized or more broadly ecosystem impacts are avoided.

Knowledge about size selectivity in the gear used to harvest krill is also important for biomass estimates from acoustic surveys where krill body length data, an essential input variable in the biomass calculation algorithm, is collected with commercial fishing gear. It is not only essential for the management of the krill fishery to achieve precise knowledge about size selectivity from the variety of fishing gear and codend constructions used but also to improve economic profit of the industry. Such information can be used to develop effective and standardized equipment that reduce fishing effort, optimize catch quantity and can also be used to design harvesting technology that targets a certain part of the population and or reduce unwanted bycatch.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Krag, L.A. et al. 2025. Assessing trawls size selectivity in Antarctic krill: The role of sex and maturity stages. Regional Studies in Marine Science Volume 87, October 2025, 104223) – discusses the results of a study that examined the cross-sections along the krill body length for each sex and maturity stage to quantify the inter sex and maturity stage selectivity of krill for a range of mesh sizes.

Study setup

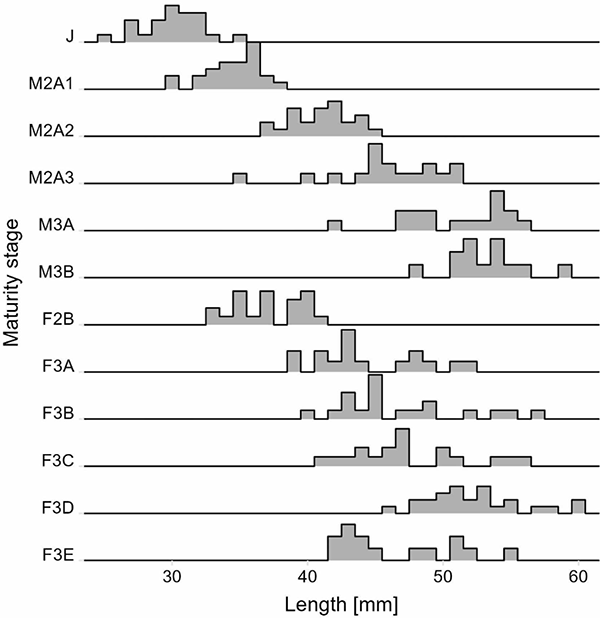

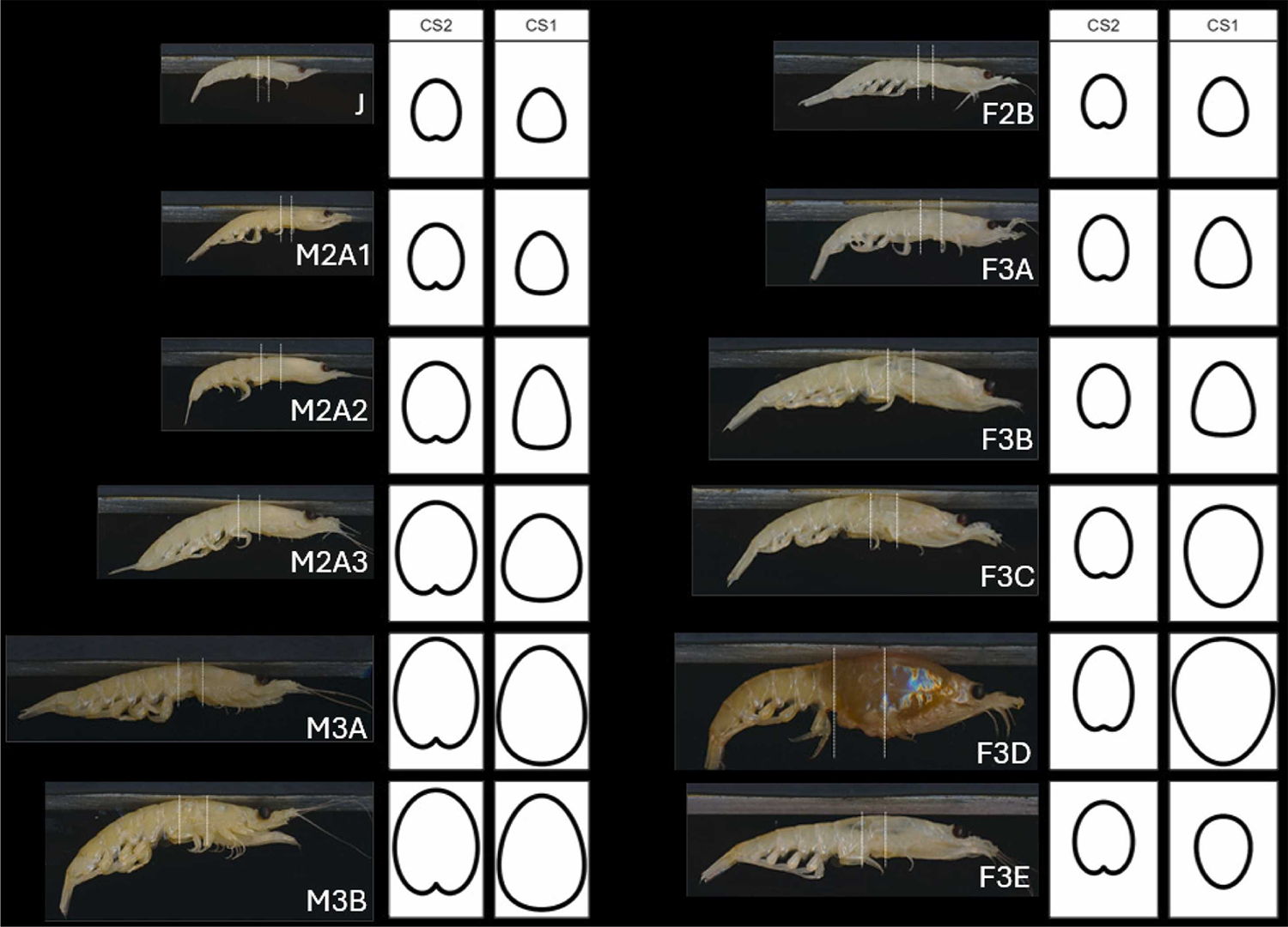

Krill samples were collected near the South Orkney Islands in conjunction with a synoptic survey run annually by the Institute of Marine Research, Norway. From the catch, detailed measurements were made of individuals to determine sex and maturity stages using established classification methods (refer to original publication for descriptions). Males were separated into three sub adult stages, namely M2A1, M2A2 and M2A3, and two adult stages, M3A and M3B. Females were separated into one sub adult stage, F2B, and five adult stages: F3A, F3B, F3C, F3D, and F3E. Juveniles, unlike all other stages, have no visible sexual characteristics. Total body length was measured (± 1 mm), and a total of 13–25 individuals were collected for each individual maturity stage.

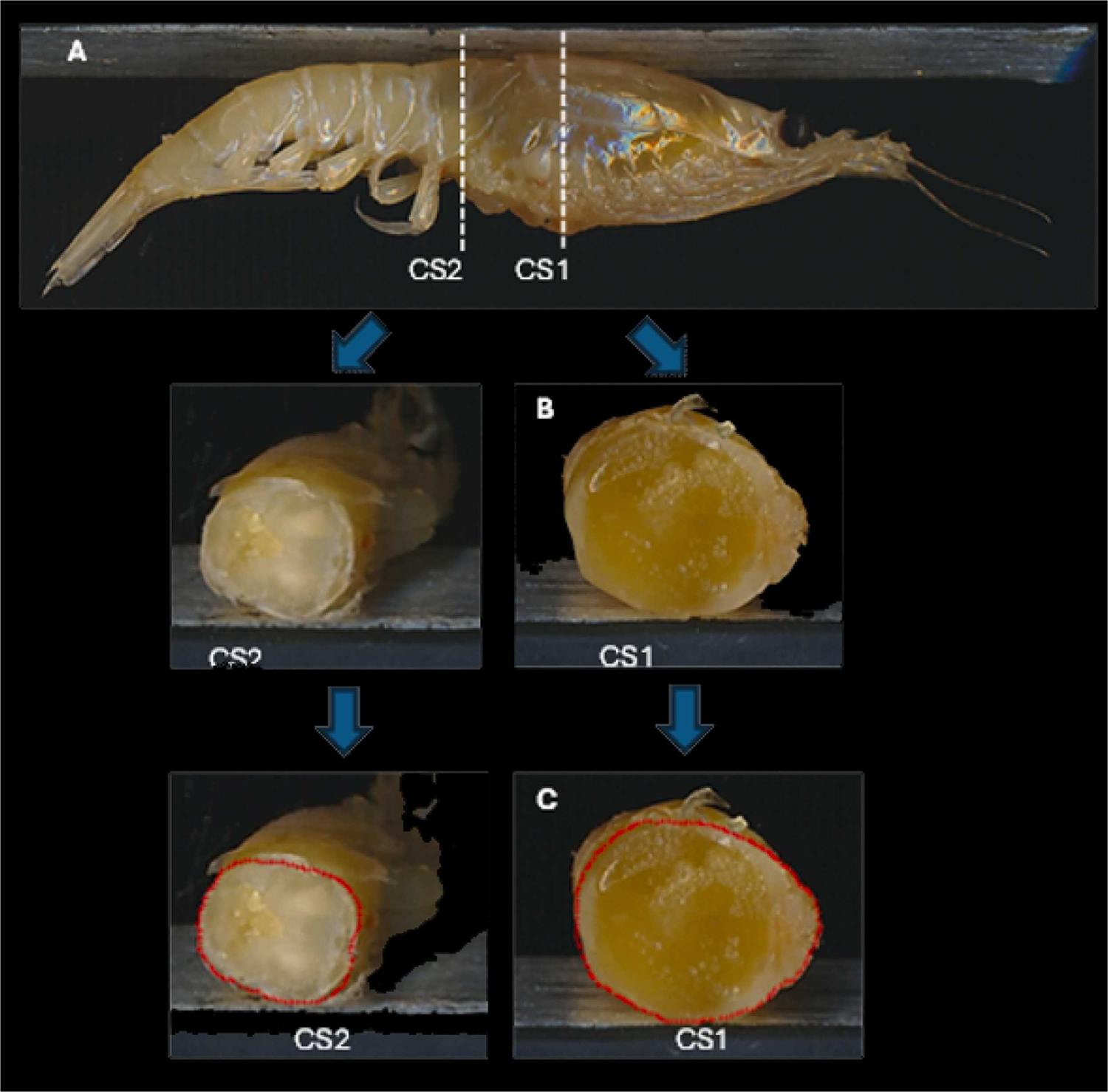

To assess potential orientations that a krill may encounter in a mesh opening, two cross-sections were measured along the longitudinal axis of a krill, CS1 and CS2, which contained the maximum height (h) and the maximum width (w). CS1 or CS2 were based on a population of individuals containing a mixture of the different maturity stages of krill. For each individual maturity stage, we started from the same position of CS1 and CS2 and examined whether it was necessary to adjust the position of CS1, CS2 or both to include maximum height and width for each maturity stage.

The morphological measurements were carried out separately for each maturity stage, one by one formalin preserved individual at the time. Each individual was placed stretched on a flatbed scanner for subsequent length measurement using the IMAGEJ software. Frozen individuals were first cut perpendicular to the length of the body at CS1 and CS2 using a scalpel, then they were placed on the flatbed scanner to acquire the images and the shape description of CS1 and CS2 (Fig. 1).

Refer to the original publication for detailed information on the experimental design, sample collection, measurements, and data analyses.

Results and discussion

Our results supplement and broaden the pooled population-based prediction of size selectivity in Krag et al. (2014) by providing a detailed sex- and maturity-stage-specific understanding of krill size selectivity in trawls. The predictions made are in good agreement with size selectivity estimates derived from experimental selectivity studies and estimations of catch patterns on commercial vessels by other researchers. These results can be used by managers to evaluate the size-selective consequences of applying different mesh sizes to different population structures, e.g., over different seasons.

The established results will further enable more accurate modeling of the fisheries’ harvest patterns and mortality on the different maturity stages in response to gear design and codend mesh sizes used. Such predictions about size selectivity can also guide the fishing industry in using mesh sizes that ensure optimal catch efficiency for a given population structure or season, thus avoiding the use of too small a mesh size that requires more energy (fuel) to tow through the water compared to a larger mesh size trawl construction.

The predicted size selectivity varies considerably across the different maturity stages. We predict L50 values (corresponding to the length at which 50 percent of the individuals in a population have gone through some transition) ranging from 34 mm (J) to 14 mm krill body length (M3A) for the mesh size and mesh opening angle range for which other researchers previously predicted an average L50 value of 32.72 mm for a pooled estimate across all maturity stages. The predicted size selectivity for the mature stages for females (F3C and F3D) is not well described by the pooled estimate by these researchers and underestimates the actual size selectivity for these more mature stages. This could indicate that mature females are underrepresented in the pooled population previously studied. Mature females obtain a larger girth than mature males at the same body length, which means that females have a higher retention probability and a lower L50 value than males for these specific maturity stages.

The morphology-based predictions of size selectivity made in this study apply for the austral summer but are expected to change over the year. The average L50 value for a population of krill containing all maturity stages is therefore expected to have a minimum during the austral summer and a maximum during the austral winter, where the maturity stage composition may be different. The noteworthy difference in the predicted size selectivity between the more mature and immature developing stages means that it is difficult to establish a universal description of size selectivity for krill across all seasons, as the proportion of particularly the more mature stages varies considerably over the year.

Knowledge of the spatial and temporal distribution and composition, e.g., data from the established fishery observer program during the fishery, can be used to establish expected average selectivity estimates for a given season and area. Quantifying the extent of this seasonal variation in size selectivity can be achieved by collecting representative population structures across seasons on major fishing grounds or management units. These structures can then be grouped into maturity stages and subjected to the maturity stage-specific size selectivity established in the current study.

Will krill fulfill its promise as an aquaculture feed ingredient?

Different trawl body and codend mesh sizes have been commercially used in the past, and the fleet still uses a range of mesh sizes in both the trawl body and the codend. The trawl body contributes to the total size selectivity process and the size selectivity of krill in commercial trawls is affected by both the trawl body and the codend. But it was recently demonstrated that krill during the fishing operation were concentrated in the vertical center of the trawl, suggesting that krill actively avoid trawl nettings, indicating that a major part of the size selectivity occurs in the codend, similar to most fish species.

If quotas for krill in the Southern Ocean change in the future based on systematic assessments and regular updates on the krill biomass and predator needs, size selectivity and possibly spatial and temporal regulation of access to harvesting of the spawning stock will become increasingly relevant. In such a scenario, managing the krill stock under more intense fishing pressure, information on the different maturity stage distribution in time and space and the size selectivity of these stages will be even more valuable.

Perspectives

Understanding the connection between maturity stages and morphology in relation to size selectivity in trawls is essential for assessing the impact of various fishing gear on the population structures of harvested species, their fishing mortality rates, and the efficiency of the gear used.

The Antarctic krill fishery is the largest in the Southern Ocean by volume, and there is increasing interest in expanding the industry. The krill fishery uses different trawl designs and is not currently subject to technical regulations specifying the types of fishing gear and mesh sizes that can legally be used. There is a need to establish a robust model predicting size selectivity that includes the morphological variation in the population of krill.

This study describes male and female Antarctic krill using 12 maturity stages, from juveniles to sexually mature adults, each with distinct morphological features. The results established a morphological description of each individual krill maturity stage to identify and parameterize what determines size selectivity using the FISHSELECT framework. This is used to predict size selectivity for each of the different stages in various mesh sizes and openings relevant to the krill fishery, in both actual and virtual populations. The results can be used to assess size selectivity for specific fishing gears and population structures, facilitating more accurate understanding and modeling of the fishery’s impact on the demographic composition of the krill stock.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Ludvig Ahm Krag

Corresponding author

Technical University of Denmark, DTU Aqua, Denmark

[107,100,46,117,116,100,46,97,117,113,97,64,107,97,108]

-

Jure Brčić

University of Split, Croatia

-

Bent Herrmann

Technical University of Denmark, DTU Aqua, Denmark

-

Marco Nalon

Technical University of Denmark, DTU Aqua, Denmark

-

Bjørn Arne Krafft

Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, Norway

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

A review of bycatch in the Antarctic krill trawl fishery

Understanding the significance of bycatch is critical to managing Antarctic krill, a keystone species and the largest fishery in the Southern Ocean.

Health & Welfare

Krill meal use reduces other costly ingredients in shrimp study diets

Due to its high protein and highly unsaturated fatty acids content, krill meal can be an effective ingredient in aquafeed.

Fisheries

Evaluating the catch efficiency for common sole with the mandatory trawl gear used in the Kattegat Sea

Regulation outside of gear specifications is needed for this common sole fishery with no additional selective device that will increase retention.

Fisheries

Developing a full-scale shaking codend to reduce the capture of small fish

A shaking codend could stimulate fish movement and increase contact probability, both of which could increase the escape chances for small redfish.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)