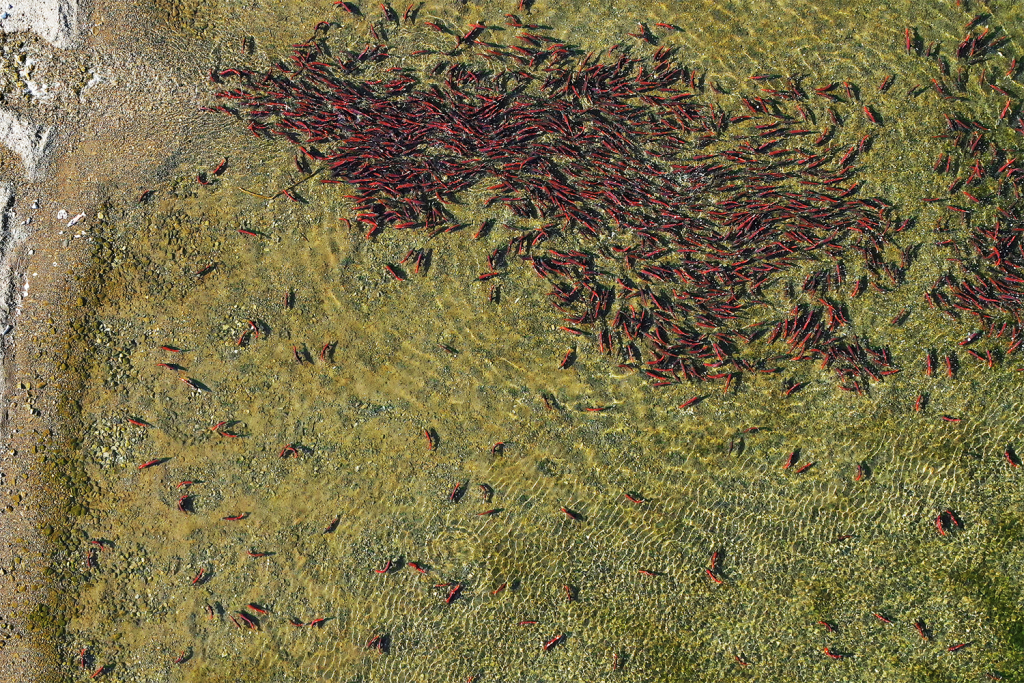

Habitat protection, restoration action and reforms to fisheries management needed, scientists say

New research holds new insights for fisheries managers looking to address wide-ranging declines among Chinook salmon stocks.

The Wild Salmon Center (WSC) with a team of leading salmon researchers from NOAA Fisheries, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Simon Fraser University, analyzed abundance trends for more than 80 Chinook salmon populations extending from California’s Sacramento River north to the Fraser River in British Columbia, Canada.

Analyzing time series data, the team found that more than 70 percent (57 of 81) of studied populations have experienced declining abundance in the last 50 years. But these trends also varied across the region: a signal that the species’ diverse strategies for migration and spawning – also known as life histories – are aiding their success in some rivers.

Taking a close look at these strategies, the team found a strong link between Chinook abundance trends and time spent in relatively cold freshwater and marine habitats. The life histories of Chinook stocks can vary widely even within the same river system. A key example of intraspecies diversity is run timing: whether a population returns to freshwater in spring, summer, or fall.

“While most populations declined, some increased in abundance,” said Dr. Will Atlas, research project lead and a watershed scientist at WSC. “Chinook populations are stable and even recovering in certain systems. Our research indicates that Chinook life history diversity has been key to the ability of some runs to thrive in the face of climate change.”

Particularly notable declines occurred in California Chinook populations – including most Sacramento and Klamath river stocks analyzed by the team – as well as interior spring Chinook returning to the Fraser, Columbia and Snake River watersheds. Southern and interior stocks have been heavily impacted by climate disturbances in recent years, suffering through both lower, hotter flows in their natal river systems as well as warmer conditions in areas of the North Pacific where they spend the ocean portion of their life cycle.

However, the team also found that in recent decades, some fall and summer Chinook populations, including those in the Fraser and Columbia, have increased in abundance. These fall and summer stocks travel north along the continental shelf to areas west of northern British Columbia and Southeast Alaska where marine waters have been slower to warm.

Some spring Chinook populations also remain strong in watersheds where cold water is reliably accessible – as well as in other systems where habitat restoration, dam removal and fish passage improvements are protecting and enhancing access to intact habitats.

“This study strongly supports the case for maintaining a diverse portfolio of wild Chinook runs across the region,” said Dr. Matt Sloat, WSC science director and a co-author of the paper. “As environmental conditions get tougher, it’s increasingly important that we understand and maintain the different survival strategies that Chinook have honed over millions of years.”

According to the scientists, a range of habitat protection and restoration actions are needed to improve habitat and flow protections for salmon, as well as reforms to fisheries management. Mixed-stock ocean fisheries pose conservation risks to weak stocks, and low abundance of some populations can close entire fishing regions, limiting opportunities for fishers to catch more abundant overlapping stocks.

According to Dr. Atlas, one responsive move would be a shift toward terminal and selective fisheries, which harvest salmon from known populations, minimizing impacts on non-target populations and species. With terminal and selective fisheries, he said, management regimes can more nimbly adjust fishing opportunities to target healthy stocks, while reducing impacts on at-risk or endangered populations.

“That’s one example of the climate-smart paradigm that we must begin to move into,” Dr. Atlas said. “When combined with the trends evidenced in our study, the recent closures show that the current system isn’t the resilient approach we need – both for fishing communities and for long-term maintenance of salmon biodiversity.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Responsible Seafood Advocate

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,114,111,116,105,100,101]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

Study: Effective fisheries management reduces extinction risk of sharks and rays

The extinction risk of sharks and rays can be significantly reduced with effective fisheries management and policies, says a Virginia Tech study.

Fisheries

Study outlines ‘impactful steps’ to improve climate resilience of U.S. fisheries

A new study has identified “actionable recommendations” to help U.S. fisheries adapt to climate change and improve climate resilience.

Fisheries

As Yukon Chinook salmon populations decline, researchers turn to technology for answers

Using drones, researchers seek to better understand where, along an almost 2,000-mile migratory route, things go wrong for Chinook salmon.

Fisheries

Study: Hatchery and fisheries management changes could help stabilize California’s Chinook salmon

NOAA-UC Santa Cruz: Changes at hatcheries and in fishery management could help restore the age structure of the state's Chinook salmon population.