A coalition of First Nations in British Columbia say the government’s decision to cancel salmon farm licenses violates UNDRIP and Indigenous rights that are protected under the Constitution

Salmon farming in British Columbia has always been met with opposition from various special interest groups concerned about the farms’ impact on wild salmon. Despite nine peer-reviewed studies showing that the province’s salmon farms pose a minimal risk to wild salmon, the opposition remains strong. In fact, the Canadian government has committed to phasing out all open net pen aquaculture in British Columbia by 2025, although that plan is on pause after the Federal Court recently ordered to set aside its decision.

To date, there are now 79 more farms at risk of being shut down. The federal government is currently deciding whether to re-issue salmon farming licenses, many of which are set to expire at the end of this month.

While the final call is up in the air, open net-pen salmon farming remains a hotly debated matter on Canada’s West Coast – including amongst Indigenous communities. Some First Nations leadership are opposed to the salmon farms and applaud the Minister’s decision, while others support it as an important source of economic opportunity that can benefit Indigenous nations.

Although the case is still before the courts, some First Nations members aren’t sitting still. A coalition comprised of members of the 17 First Nations that have agreements with the industry has been formed to advocate for the re-issuing of salmon farming licenses in the region.

Moreover, two First Nations in British Columbia have announced plans to create an “Aquaculture Zone” in their traditional territories. Specifically, they’ll administer their own licensing programs for salmon and shellfish farms, regardless of what the Canadian government has to say about it. It’s a bold move, but the First Nations argue that’s rooted in Indigenous rights protected by the Canadian Constitution. If the Canadian government succeeds at closing down open-net fish farming, could this strategy offer a way forward for Indigenous-owned and -operated aquaculture operations at risk of closure?

No consensus among First Nations

There are diverse perspectives on the issue of open net-pen salmon farming, and that extends to within and between Indigenous communities. In the Federal Court’s 66-page ruling, the First Nations Fisheries Council of British Columbia, the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations (BCAFN), the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and the First Nations Summit are all listed as interveners in the consolidated applications for judicial review, standing alongside the David Suzuki Foundation and other prominent Canadian environmental advocacy groups in opposing open-net fishing farming.

“Some of the First Nations express fear that the presence of farmed salmon in the waters of the Fraser River presents a risk to wild salmon population, particularly the risk of disease,” wrote Justice Elizabeth Heneghan in the Federal Court ruling. “Submissions were made about sea lice and the piscine orthoreovirus (PRV).”

Most recently, the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations spoke out against the recent Federal Court ruling and denounced the applications of Mowi Canada West, Inc., Cermaq Canada Ltd. and Grieg Seafood BC Ltd. (“the Applicants”) to overturn the Discovery Islands decision.

“The First Nations Leadership Council calls for the decision to be upheld,” wrote the BCAFN in a statement on their website. “It is clear that the majority of First Nations in B.C. oppose open net pen fish farming due to the detrimental effects it has on wild salmon: the 102 First Nations that support the removal of fish farms from the ocean are supportive of Minister Jordan’s decision.”

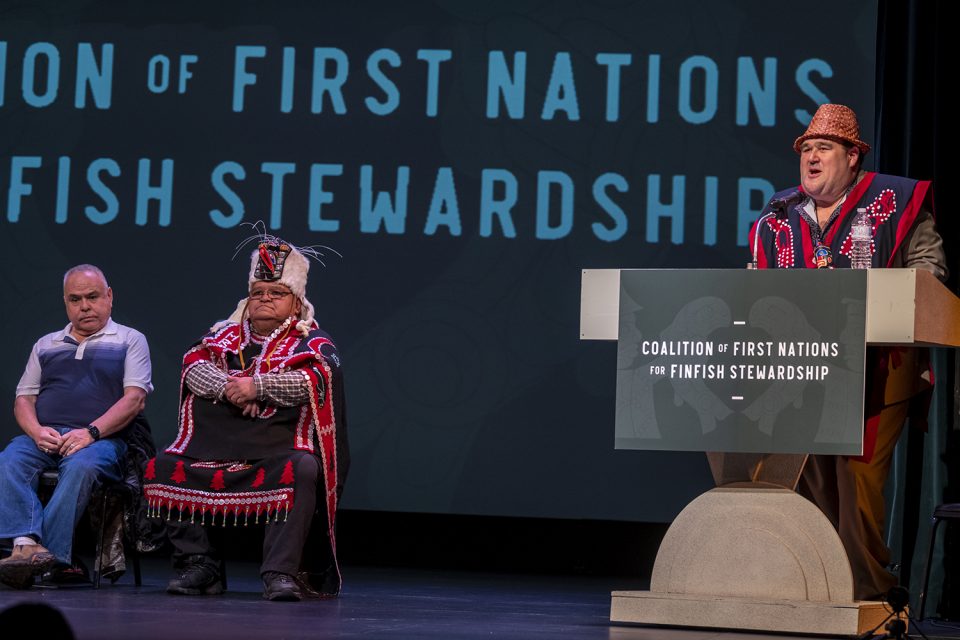

However, other First Nations claim that community consensus has not been reached on the issue. After the closures were announced in December 2020, a coalition of First Nations came together to demand that the federal government immediately re-issue salmon farming licenses in their territories. First Nations for Finfish Stewardship asserts that the closures of salmon farms in their territories represent a violation of Indigenous rights and have joined forces to assert their inherent right to self-governance.

The Advocate spoke to Dallas Smith, the spokesperson for the First Nations for Finfish Stewardship and a member of the Tlowitsis First Nations, who said that the coalition came together after seeing what happened in the Discovery Islands. There are 14 nations in the coalition, led by the Tlowitsis, Wei Wai Kum, Ahousaht and Kitasoo Xai’xais Nations.

“During the Discovery Islands process, the First Nations communities who have rights and titles in the Discovery Islands tried to get an exemption to finish the growth cycle, which would have gone six months beyond the closures,” said Smith. “Minister Jordan turned it down because of ‘social acceptability.’ All of us then started to wonder, ‘What’s at stake for us here if they decide to close the rest?’”

Although 17 nations currently have formal agreements with salmon farming companies, only 14 are members of the coalition, with Smith saying that First Nations have not reached a consensus on how salmon farming should be handled. Rather, their agreement is that as sovereign nations, it’s their right to be able to decide for themselves.

“This coalition is a group of autonomous nations trying to figure out how salmon farming can fit into their territories,” Smith said. “Everyone has autonomous visions on what the regulations should be, like revenue sharing, stewardship, etc.”

For himself and his territory, Smith said salmon farming represents an opportunity for training and education of future generations and increased support of small businesses, which is vital in remote areas, but the uncertainty has him worried about the consequences of a potential closure on his community.

“The jobs that are at stake right now, they’re not simply absorbable,” he said. “New jobs don’t simply exist in these communities because of the remote factors of them. The impacts would be devastating.”

The court document speaks to that reality, including an affidavit from James Walkus – a contractor for Mowi and a First Nation commercial fisherman who primarily employs Indigenous people. His company, the James Walkus Fishing Company, transports fish from the farms to processing plants, which comprises approximately 30 percent of his company’s business.

In his affidavit, Mr. Walkus described the implications of the government’s decision on his business, his family and the community. Moreover, he said that his First Nation and other affected communities were not included in the Minister’s consultations – an alleged oversight that could arguably be in violation of Canada’s legal duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous groups on matters that may “adversely impact potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights.”

Likewise, Smith said the government decision-makers behind the license renewals have not properly engaged with the affected First Nations communities. The Minister did meet with the coalition in March 2022, but she has yet to visit one of the salmon farms herself.

Leading scientists defend Canada’s peer-reviewed science advisory process on salmon farming

The scapegoat

Where other regions of the world have embraced aquaculture expansion, the Pacific coast of Canada seems to be one place where the industry’s presence has stirred debate since the beginning. Smith speculated that the reason for the polarization in British Columbia is the power of special interest groups who see salmon farming as the sole driver of wild salmon population declines.

“There are so many stressors on wild salmon, but salmon farming is an easy smoking gun. To support it publicly comes with personal attacks and lateral violence,” Smith said, explaining why it’s been difficult to accurately tell the salmon farming story in B.C. and show the public which communities are in support of renewing the licenses. “The activists have been able to create so much social division. It’s dangerous.”

There is also a divide between and amongst nations when it comes to salmon farming. Although the coalition is made up of some of the 17 nations who currently have agreements with the salmon farming industry, not all are members and of those who are, many do not want their support to be made public.

On the division between nations, Smith said: “First Nations in our coalition have united over a concern that our rights to make economic decisions for our territories are being ignored when it comes to the salmon farming sector. While we respect the decision made by some Nations to remove farms from their territories, we expect the same in return for those Nations who would like to keep working with the sector. This is how we acknowledge genuine self-governance and economic self-determination as Rightsholders.”

When asked about the possible impacts of the decision on Indigenous communities, the Honorable Joyce Murray, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and Canadian Coast Guard, reiterated the government’s commitment to achieving reconciliation with Indigenous communities.

“As part of Canada’s commitment to reconciliation, continued and close collaboration with Indigenous communities, the Province of British Columbia, industry, scientists and other stakeholders will be key to developing a responsible plan and successful transition process, ” wrote Murray’s office in an email. “DFO is in consultation with the license holders and a decision will be made in due course. The transition will provide a vision to create economic opportunities for communities that rely on fish farming.”

However, some First Nations say they don’t need the stamp of approval from the federal government to proceed.

There have already been public commitments by Nations administering their own fisheries and aquaculture licensing regimes in an attempt to re-assert their authority over their territories, including how fish farming and fisheries will be managed.

The Gwa’sala-Nakwaxda’xw First Nation located in Port Hardy has issued the following statement about their plans to administer their own licensing regime if the government fails to renew their salmon farming licenses: “The Nation is planning to administer its own fisheries and aquaculture licensing regime after a failure of the Canadian government to: a) conserve their fish stocks through permitting of overfishing and b) adequately mitigate impacts from resource development. For the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw, implementing local First Nations management practice is the only pathway to recovering fish stocks and supporting their local community economy at the same time.”

Smith said that if the licenses are not renewed, individual nations will each take their own course of action, and he did not rule out the possibility of more nations pursuing their own licensing regimes.

The jobs that are at stake right now, they’re not simply absorbable. New jobs don’t simply exist in these communities because of the remote factors of them. The impacts would be devastating.

‘We want to be leaders in the blue economy’

Despite the recent federal court ruling that rejects the proposed closures, the minister remains committed to upholding the government’s promise to close the salmon farms.

“Minister Murray is committed to transitioning away from open-net pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters,” wrote Claire Teichman, Press Secretary to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, on behalf of the minister. “Last spring an extensive set of engagements on a plan to phase out open-net pen fish farms was conducted, and the views of multiple stakeholders recorded. The ‘What We Heard’ report was published and posted online in July 2021, and DFO officials are in the process of building on this work.

In the long term, Smith said the government and First Nation communities need to work together to find a better ongoing oversight process so these decisions are more transparent. Despite the continued uncertainty, he remains hopeful that aquaculture has a place in his community: “We want to be leaders in the blue economy and we think that the aquaculture sector really fits and complements that.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Emily De Sousa

Emily is a fisheries scientist and a social media influencer based in Niagara, Ontario, Canada. She is the founder of Seaside with Emily, an online travel and seafood blog. She works in the Coastal Routes lab, where her research focuses on alternative seafood networks in North America.

(Instagram: @seasidewithemily, Twitter: @emilyseaside, Linkedin: Emily De Sousa)

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

British Columbia salmon farmers wary of Liberal government’s aquaculture plans

The Canadian Liberal Government’s announcement of Aquaculture Act left the industry feeling anxious while some stakeholders say they were completely left out of the process.

Responsibility

Aquaculture Exchange: Corey Peet

Shrimp farming expert Corey Peet discusses the work of convening multiple stakeholders in Southeast Asia, the role of certification and the dynamics of sustainability challenges confronting marketplace demands.

Intelligence

Canadians largely support ocean-based salmon farming, yet farms are being shut down

Amid a dizzying landscape of passions and politics, a recent survey showed the confusing messages Canadians are getting about salmon farming.

Innovation & Investment

Competitiveness comes at scale for RAS operations

Total RAS salmon production worldwide is less than half of 1 percent of total production. Many of the investors flocking to the sector now are new to fish farming, and confident in its potential.