Marine mammal ‘pingers’ and seabird-sparing fishing hooks are just two ways in which commercial fishing is addressing a longstanding issue

Every year, global fisheries are responsible for millions of pounds of bycatch, the term that refers to the discarded catch of any living marine resource – dead, alive or injured – due to a direct encounter with fishing gear. According to the World Wildlife Foundation, bycatch constitutes 40 percent of fish catch worldwide – some 38 million metric tons (MT) of sea creatures. Among that bycatch every year is 300,000 small whales and dolphins, 250,000 endangered turtles and 300,000 seabirds.

In its 2005 National Bycatch Report, NOAA estimated fish bycatch in the United States alone to be in the region of 1.2 billion pounds. In the Southeast alone, the bycatch number was three times larger than actual fish landings, totaling 682,000 pounds.

Recognizing the scale of this problem, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) established a National Bycatch Reduction Strategy in 2016, an implementation plan for that strategy for 2020 to 2024 and various marine mammal take-reduction plans. The organization works with partners including fishery management councils, marine mammal take-reduction teams, environmental organizations and fishing industry groups to reduce bycatch.

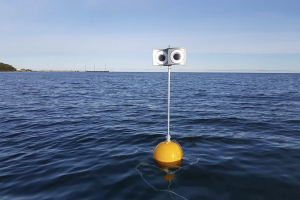

Private companies like Fishtek Marine and Hookpod have also developed innovative technologies to address the problem. Based in Devon, England, Fishtek Marine has been developing solutions for bycatch for the past five years, including anti-depredation pingers, looming-eye buoys, deterrent pingers and more.

Its dolphin anti-depredation pinger is an acoustic device designed to scare dolphins from poaching fish, while the banana pinger has variations to alert whales, dolphins and porpoises. The looming eye buoy is designed to prevent birds from diving into gillnets while the netlight illuminates gillnets to deter sea turtles, small cetaceans and seabirds. The SharkGuard, still a prototype, emits an electrical pulse around longline hooks that is sufficiently powerful to deter sharks from taking baited hooks and that could reduce shark bycatch by 91 percent.

Rob Enever, head of science and uptake at Fishtek, said there are three main incentives for fishermen to use the company’s products: top-down legislation from government, bottom-up incentives (where fishermen recognize the bycatch problem and want to resolve it) and pressure from retailers.

“In the next decade retailers are going to require their supply chains to be more environmentally responsible, and that’s the driver that we believe will change most over the coming years,” he said.

The seafood technology we didn’t know we needed: a sea urchin vacuum

Fishtek Marine is beginning to collaborate with supermarket retailers and inform them how the fisheries they buy from could improve their practices.

“This is a way more effective way of incentivizing fishermen to use these bycatch deterrent devices,” he said. “With top-down legislation, if fishermen don’t comply they can often still get away with it. But if retailers stop buying their fish – that’s a powerful incentive to change practices.”

Becky Ingham, CEO of Devon, UK-based Hookpod, agrees: “If you can get retailers to question their source fisheries about their bycatch issues, you’d have pressure on fisheries to improve practices,” she said.

Hookpod has two products, both designed to reduce seabird bycatch in longline fishing. The products are attached to baited hooks until those hooks reach depths of 20 meters below the surface, at which point the Hookpods unclip, exposing the hook.

Ingham cited statistics from Birdlife International, which estimates that of the 300,000 seabirds killed by longline fisheries each year, 100,000 of them are albatrosses. Some 15 species of albatross are threatened, and their main threat is longline fishing.

Hookpod could offer a solution. Several peer-reviewed studies have been conducted on the efficacy of Hookpod’s products, with one 2017 study published in Animal Conservation demonstrating that the Hookpod is “highly effective” at reducing seabird bycatch without negatively impacting target catch rates and has potential for reducing bycatch rates on other threatened species (e.g., marine turtles). Renowned nature enthusiast and activist Sir David Attenborough wrote a testimonial for the product, saying albatrosses are “magnificent ocean wanderers.”

Ingham met with the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership and a roundtable of tuna suppliers in 2019 and recently collaborated with Aldi International, which agreed to purchase 3,000 Hookpods to use on two of their tuna fisheries’ vessels.

“This way, those vessel captains will be able to compare seabird bycatch with Hookpods, to bycatch without, and they’ll have the assurance that the new tech doesn’t interfere with the catch,” she said. “We need to have fishermen on our side, so we need to demonstrate that there won’t be an impact on their target catch.”

Currently, Hookpod has been fielding inquiries from Publix and Walmart and Ingham is optimistic about the future.

“By next year this time, I think we’ll have three-to-four of these projects up and running,” she said. “These projects will demonstrate that pressure from the retail supply chain and from consumers can have an impact on fisheries and on the environment.”

The cost of the Hookpods is minimal in the larger context, she added, with the Hookpod Mini costing (U.S.) $6 each. So a boat with 1,000 hooks would involve a $6,000 investment, but Ingham said the longer-term benefits of the product could cancel out the start-up cost.

“Our products last at least three years, so that’s $2,000 per year,” she said. “But if you eliminate the bycatch of just one bird that prevents you from catching a tuna, you’ve made that money back already. If you catch 10 seabirds, that’s 10 lost opportunities to catch fish. If you take into account staffing, licenses, quota and the scale of operations we’re talking about, the price of Hookpods shouldn’t be a dealbreaker.”

Overall, getting the Hookpods to fishermen has been an uphill struggle, she added. “Fishery is not an easy industry in which to effect change, but fishermen who use our product like it. This isn’t an expensive piece of gear and there’s lots of money in conservation for funding for those who need it.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lauren Kramer

Vancouver-based correspondent Lauren Kramer has written about the seafood industry for the past 15 years.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

Can handheld DNA testing technology stand up to seafood fraud?

The MasSpec Pen, developed to diagnose tumors, can identify fish species by touching the tip to a sample. But the species database is lacking.

Aquafeeds

IFFO, GAA urge Asian trawl fisheries to improve stocks, product quality

Fisheries improvements projects (FIPs) are an important mechanism for bettering South East Asian fisheries that supply into the aquafeed industry, a new report finds.

Intelligence

Off the Knife with Barton Seaver

In the second Off the Knife interview with chefs and foodservice professionals, Barton Seaver tells the Advocate that while restaurant employees shouldn’t have to recite sustainability science at tables, they can personalize their knowledge and effectively communicate the method behind the menu.

Intelligence

Seaspiracy film assails fishing and aquaculture sectors that seem ready for a good fight

Seaspiracy, a new Netflix documentary-style film, depicts the fishing and aquaculture in an ugly fashion but the industry response is swift.