The pollock fleet uses extensive tools to minimize salmon bycatch, yet declining salmon runs and rising scrutiny make issue increasingly complex

For Maverick Blake, captain of the Alaska pollock fishing vessel Progress, pulling up salmon in a trawl net is nothing short of devastating.

“My heart sinks when that happens,” he said. “In the wheelhouse, my face drops into my hands. All my guys are deflated and looking at their boots. Catching salmon is our worst nightmare.”

Like all pollock trawlers in the Bering Sea, the Progress uses a suite of bycatch prevention measures to keep numbers as low as possible. Its fishing gear includes salmon excluders – built-in devices or modifications to fishing nets that allow salmon to escape while retaining the targeted fish. Fleetwide data sharing helps fishermen avoid hotspots in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska where salmon are present. And 24/7 electronic monitoring or the presence human observers on board the vessels ensure crew accountability every step of the way.

Avoiding salmon comes at a price. For Blake and his crew, it often means travelling further offshore to reach what they call “clean” fishing grounds.

“On most catcher boats we pay our portion of the fuel. If an area we previously fished, say 80 miles from town, is inundated with salmon, we might have to travel 200 miles instead. And if there are no fish at 200 miles, we might have to go 400 miles,” he said. “Sometimes that means 5,000 gallons of fuel per trip, which eats into our profit margin.”

Fifteen years ago, a cap on Chinook (king salmon) bycatch was instituted. To keep the pollock fleet from blowing past that limit – and facing a shut down – the federally appointed North Pacific Fishery Management Council allowed the Bering Sea pollock industry to design its own management tools to stay under the cap. The industry developed Salmon Incentive Plan Agreements (IPAs) to help promote stronger conservation practices and reduce interactions with salmon.

Weekly bycatch closures are announced via Starlink, and more recently, the Bristol Bay Science & Research Institute launched a weekly genetics testing program on chum salmon bycatch. So far, the testing has focused solely on chum, but the results have been eye-opening: the majority of the chum bycatch originates from hatcheries in Russia or Japan – not fish from Alaska.

There’s a lot at stake when it comes to avoiding bycatch. The pollock industry is under fire in the wake of a severe crash in the number of Chinook and chum salmon on Alaska’s Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers. In 2024, Alaska state managers and First Nations in Canada signed a seven-year agreement that closed Chinook fishing on the mainstream Yukon River and Canadian tributaries.

For many Indigenous communities, the situation feels unjust: Their subsistence harvests have been halted while commercial fishing at sea continues, and many have pointed to the pollock fleet as a culprit of the decline.

“It’s an incredibly painful situation for subsistence users, because their way of life is being taken away from them,” said Caitlyn Yeager, VP, policy and engagement for the At Sea Processors Association. “This is not their economy, it’s how they live, and the salmon have cultural and nutritional importance to them.”

The causes behind the crash are complicated, she added, and with so many different fisheries operating in Alaska, it can be hard to get the facts on how each one is managed. “Among Alaska Natives, it’s led to the perception, ‘If we can’t fish, how come you can?’”

The pollock industry argues that the accusation, while understandable, is not supported by the evidence. Bycatch numbers have steadily improved, backed by data collected from onboard human or electronic monitoring. Chinook salmon returns to the rivers, however, have not shown the same rebound.

“According to scientists, the crash of Chinook and chum salmon on these rivers is driven by climate related changes,” said Julie Decker, president of the Pacific Seafood Processors Association. “Other studies are showing that permafrost melt in northern Alaska is exposing naturally occurring minerals to the rivers and changing the chemical composition of these northern rivers. It actually stains them orange. This chemical change has been linked to a lower survival of fish in these same rivers. But these are large, difficult problems to solve.”

She added that the Alaska pollock fishery is carefully managed, observed and monitored, and the IPAs are written contracts revisited each year with NOAA.

“In the Bering Sea, the Chinook cap is allocated all the way down to the individual vessel level. Each vessel has its own cap and is responsible for managing it,” said Decker. “If they don’t, they can get shut down.”

The industry’s bycatch rate of 2 percent is already considered very low, according to Yeager.

“The Alaska pollock industry has one of the lowest bycatch figures of any fishery – not just salmon, but all bycatch,” she noted. “We’re incredibly proud of fisheries management in the North Pacific. The IPAs allow us to provide public transparency with governmental oversight, which has led to huge reductions in salmon bycatch and other stocks of importance to Alaska. This is a complicated issue, and we continue to hold that the primary drivers behind declines in salmon are the ecosystem impacts we see from climate change. But we’re trying to drive down our numbers and use data to inform our movement on a constant basis.”

Back in the early 2000s, the pollock industry launched its rolling hotspot program. Fishermen tracked where they encountered the most salmon and closed those areas on a weekly basis. Those rolling closures, coupled with constant monitoring, are still the most effective ways to reduce bycatch, Yeager said.

“Fish have tails, and they move, so drawing boxes in the ocean as a static closure is a short-lived solution,” she said.

Yeager added that genetic testing has revealed an important nuance: only about 50 percent of the Chinook bycatch and just 17 percent of chum bycatch originate from western Alaska origin. Most of the chum, she said, comes from overseas hatcheries in Russia and Japan.

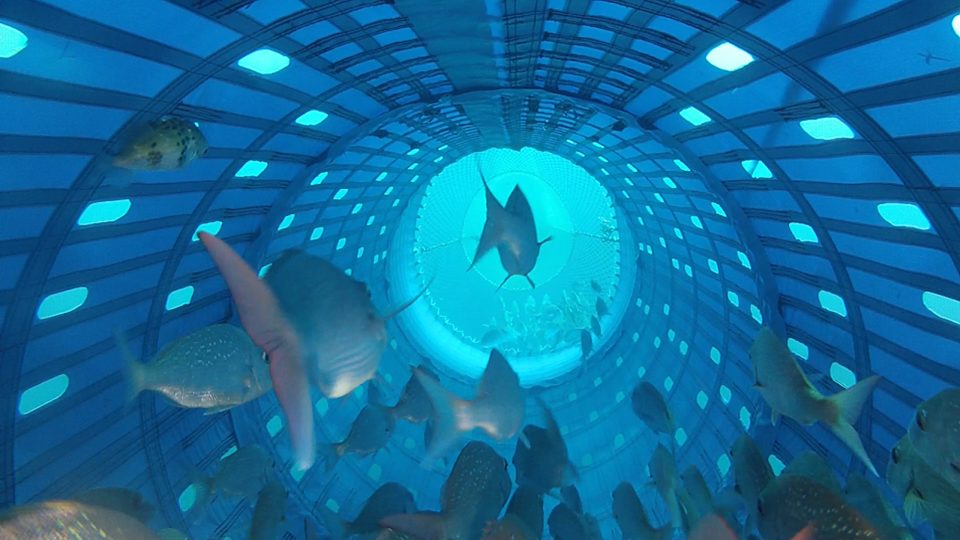

‘A world down below’ – Deeper fishing insights lead to better tools for bycatch reduction

“Teasing out those differences has helped us try to improve the stocks we’re really concerned about – like those in the Yukon and elsewhere,” she said. “The data told us we need to get better at learning what areas are inhabited by western Alaska chum. Getting genetic information on chum salmon bycatch on a weekly basis has been a complete gamechanger for our industry.”

For years, the pollock industry assumed its long-term efforts to reduce bycatch spoke for itself. But today, the megaphone of social media has amplified other voices.

“Across the globe, we’ve seen a cultural shift where people are getting their information from other sources,” Yaeger said. “Today, if you don’t tell your story, someone else will. The Alaska Pollock Fishery Alliance is a unified voice for our industry, trying to correct some of these narratives, but because our critics tend to take the worst parts of federal and state fisheries management and lump us all together, we need to get out there more often. Our work is really a marathon, and we need all the voices from the industry on this very charged subject.”

Fisherman Maverick Blake agrees: “This is a science-based fishery, which in my opinion is the most effective way to ensure the health of the marine environment. There’s no guesswork in what we do,” he said. “But instead of looking at ocean acidification or warming, or the movement of hatchery salmon, the pollock industry is a scapegoat here. A lot of the science is being ignored.”

“No one wants to catch these salmon,” he continued. “This is our livelihood, and we want to be good stewards of the ocean. That’s why we’re continually investing in research and technology to reduce our bycatch, year over year. Bycatch affects my career and how I feel about what I’m doing, and as a young, 33-year-old captain, I want to show I’m responsible, and fish clean and smart. It’s not that my family is more important than families that now cannot put salmon in their smokehouse. It just seems a little unfair to only look at this from your side of the sandbox.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lauren Kramer

Vancouver-based correspondent Lauren Kramer has written about the seafood industry for the past 15 years.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

‘We were just looking for a way to fish better’: How one partnership is reinventing commercial fishing nets to reduce bycatch and improve animal welfare

Precision Seafood Harvesting’s novel reimagining of commercial fishing nets provides innovative solutions to both bycatch and animal welfare issues.

Fisheries

A review of bycatch in the Antarctic krill trawl fishery

Understanding the significance of bycatch is critical to managing Antarctic krill, a keystone species and the largest fishery in the Southern Ocean.

Fisheries

‘Here to stay and evolving fast’: How GreenFish’s AI-powered fish-forecasting tech is modernizing commercial fisheries

GreenFish uses AI and datasets to predict fishing hotspots, helping commercial fisheries save fuel, time and maximize catch value.

Fisheries

FAO: 64.5% of global stocks are sustainably fished, but overfishing persists without management

FAO’s most detailed fishery review shows 64.5 percent of stocks are fished sustainably, but regional gaps and overfishing trends persist.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)