Examining the sources, toxic impacts and mitigation paths for microplastics pollution

Microplastics present several major long-term threats to ocean ecosystems and marine life. Microplastics can harm fish or other species that ingest the materials and can carry toxic chemicals that can biomagnify up the ocean food web and into seafood products consumed by humans.

A study by Xuexia Zhu and co-workers reviews the pervasive impacts of microplastics (<5 mm in size) and nanoplastics (<1 µm in size) on fish embryos, larvae and juveniles, emphasizing their vulnerability due to immature systems, rapid growth and limited defenses.

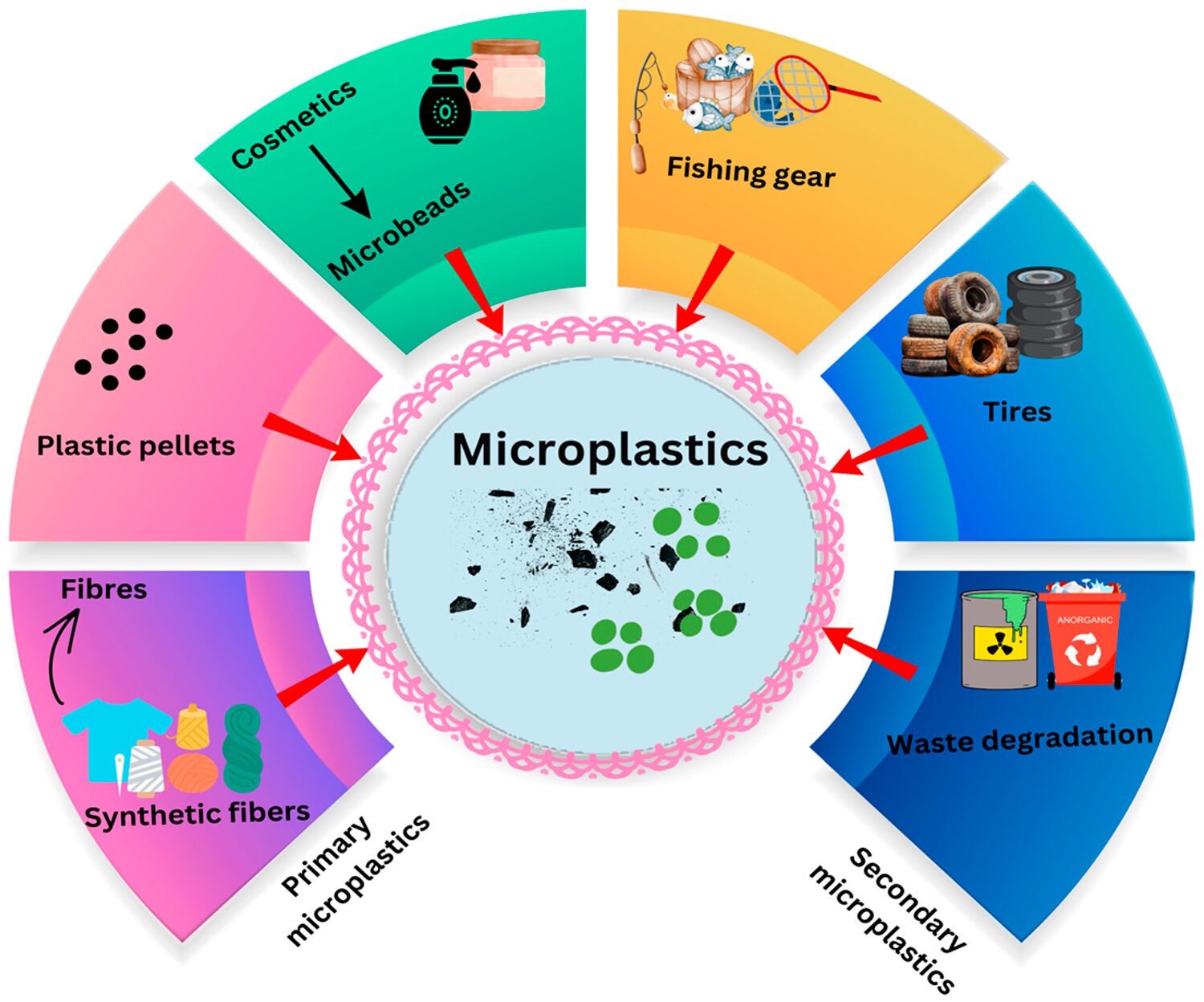

Sources are classified as primary (manufactured particles from cosmetics, textiles, detergents, paints, agriculture, and industrial pellets) and secondary (degraded from larger plastics via UV, abrasion and biological processes, mainly from packaging, construction and automotive waste).

Global plastic production exceeded 400 million tons in 2022, with 4.8–12.7 million tons entering oceans annually; land-based sources (80 percent) include urban runoff, wastewater and tire wear, while sea-based sources (20 percent) involve fishing gear.

Exposure pathways for early fish stages include ingestion (mistaking microplastics for prey, leading to gut blockages and malnutrition), surface adhesion (to eggs/chorions, blocking oxygen and development), gill uptake, tissue translocation and maternal transfer. Smaller particles increase bioavailability, penetrating barriers and accumulating in guts, gills, liver, kidneys and muscles. Toxicity mechanisms encompass physical harm (abrasions, organ defects like cardiac arrhythmia in zebrafish), chemical leaching (additives like phthalates and others causing endocrine disruption), adsorbed pollutants (heavy metals, oxidative stress simplifiers, lipid peroxidation and inflammation markers) and behavioral changes (erratic swimming, reduced predator avoidance).

Ecological consequences are severe for the fish affected: reduced hatchability, growth retardation, higher mortality, weakened immunity, neurotoxicity, metabolic dysfunction and reproductive impairments. Bioaccumulation is highest in gastrointestinal tracts, with trophic transfer magnifying levels (3–11x in mysids-to-fish chains) and potential biomagnification in food webs (e.g., mackerel to seals), though variable and often diluted. Carnivorous/omnivorous fish show higher ingestion (6.09 vs. 1.88 MPs in herbivores), with sublethal effects reducing animal fitness, fecundity,and population stability, disrupting ecosystems and fisheries.

The mitigation strategies discussed advocate uniform detection methods, long-term exposure studies, pollution controls (waste reduction, wastewater filtration), regulations (microbead bans), bioremediation and natural diets to minimize ingestion. Overall, the authors highlight the need for integrative research on co-pollutants, biomarkers and ecosystem monitoring to safeguard biodiversity.

Relevance of research findings to the industry

These findings are crucial for fisheries and aquaculture, where early life stages are bottlenecks for stock replenishment. High vulnerability in nurseries (estuaries, coastal zones) informs site selection and habitat protection, reducing exposure from hotspots like urban runoff.

The aquaculture industry can adopt microplastics-free feeds, advanced filtration in hatcheries and monitoring protocols to boost survival rates and yield. And for the commercial fishing industry, understanding trophic transfer aids sustainable practices, like targeting less contaminated species or advocating gear alternatives to cut sea-based sources.

Environmental industries benefit from standardized detection (e.g., gas chromatography–mass spectrometry techniques) for compliance, while plastic manufacturers face pressure for eco-friendly alternatives and waste management. Overall, authors strongly support policy-driven reductions in plastic pollution, enhancing economic resilience in a U.S. $400 billion global fisheries sector threatened by biodiversity loss.

Perspectives

Looking ahead, the authors underscore the need for urgent, multifaceted action to curb microplastics pollution, given its irreversible potential if unaddressed. Future research should prioritize nanoplastics, sublethal chronic effects and synergistic interactions with other stressors like climate change, using advanced biomarkers and long-term field studies to bridge lab-to-ecosystem gaps.

Policy perspectives emphasize global cooperation, such as expanding microbead bans and enforcing FAO/UN guidelines for marine litter reduction. Technological innovations in biodegradable polymers and AI-driven monitoring could transform mitigation, while public awareness campaigns foster behavioral changes in plastic use.

Optimistically, evidence of resilience in some species (e.g., no growth impact in medaka at certain doses) suggests adaptive potential, but without intervention, escalating microplastics levels risk cascading ecosystem collapses, emphasizing the need for a circular economy to protect aquatic life, fisheries and human health.

Could a rise in pink salmon populations drive Atlantic salmon declines?

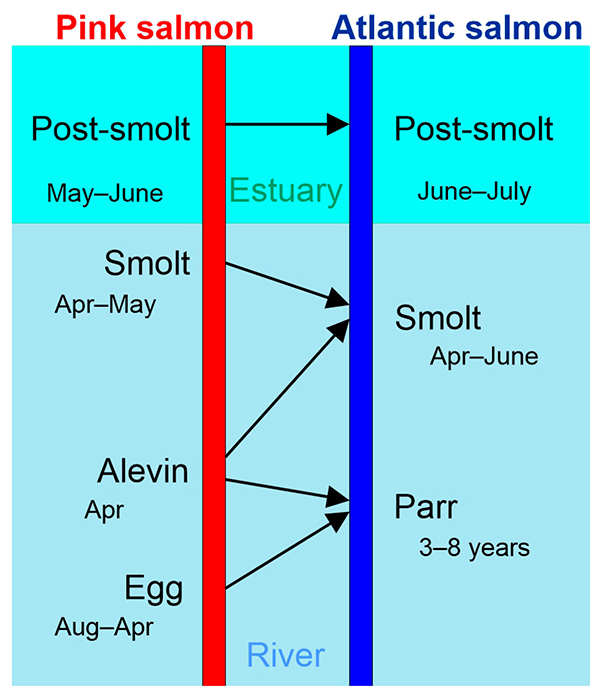

This review by Marja Keinänen and Pekka J. Vuorinen examines how exploding pink salmon populations could drive Atlantic salmon declines in northern European rivers like the River Teno (Tana, on the Finland-Norway border). Pink salmon, introduced to the Kola Peninsula in the 1950s–1990s, now form self-sustaining invasions with biennial booms in odd-numbered years.

In the Teno, pink ascents rose from ~5,000 in 2017 to 150,000 in 2023, depositing ~116 million eggs versus Atlantic salmon’s ~43 million. Concurrently, Atlantic salmon populations have crashed: one-sea-winter returns fell to 11 percent of 2014–2018 levels by 2024, while parr densities dropped from 12.6–16.3 to 7.3 – 10.3 per 100 square meters post-2018, and fishing bans were imposed since 2021.

“Pink salmon indirectly harm Atlantic salmon via nutritional imbalances across life stages,” was the central hypothesis

evaluated in this study. In rivers, Atlantic parr and smolts prey on lipid-rich pink eggs (11–21 percent dry weight lipid, 10–11 kJ/g energy) and alevins (emerging March–May), shifting from low-lipid invertebrates (3–5 kJ/g, <6 percent lipid) to high omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs, especially DHA). This elevates lipid peroxidation – the oxidation of unsaturated fats producing toxins – thus depleting thiamine (vitamin B1) – essential for energy metabolism and as an antioxidant. Thiamine demand rises (≥0.36 nmol/kJ for growth, higher against peroxidation), while suboptimal protein-to-lipid ratios (<1.88) hinder muscle development and smoltification.

In estuaries and seas, abundant pink post-smolts (30–91 million vs. 1–2 million Atlantic smolts) become prey, exacerbating high-lipid, omega-3 PUFA intake. Parallels are drawn to Baltic Sea M74 syndrome, where fatty sprat/herring diets cause thiamine deficiency, low survival and poor returns. Additional factors include invertebrate competition (pink alevins displace parr) and nutrient enrichment from carcasses (boosting productivity but risking hypoxia). It is worth noting that preventing pink ascents (e.g., dams, targeted removals) has aided partial recoveries of Atlantic salmon.

Relevance of research findings to the industry

The findings are highly relevant to commercial and recreational salmon fisheries, aquaculture, and conservation management in northern Europe. Atlantic salmon supports valuable economies (e.g., tourism, angling on the Teno before bans), but declines threaten jobs and revenue. The invasive pink salmon link highlights urgent needs for control measures – such as the successful 2023 barriers/removals which correlated with better Atlantic returns – potentially allowing sustainable harvests.

Perspectives

Authors suggest considering targeted studies, such as comparing Atlantic salmon physiology (thiamine, stress marker levels, growth) in high- vs. low-pink years; conducting feeding trials to quantify peroxidation thresholds; and modeling food-web impacts under climate warming, which may favor pink expansion. Ecologically, pink salmon could reshape Arctic rivers as “regime shifters,” affecting nutrient cycles, predators (birds and bears) and biodiversity.

Management perspectives emphasize proactive biosecurity: international cooperation, community reporting and ethical debates on eradication vs. coexistence. If validated, study findings could guide adaptive policies for healthier stocks amid invasives and climate pressures, mirroring global cases like lionfish.

Production of juvenile sardines in ecological culture systems could provide opportunities for fisheries

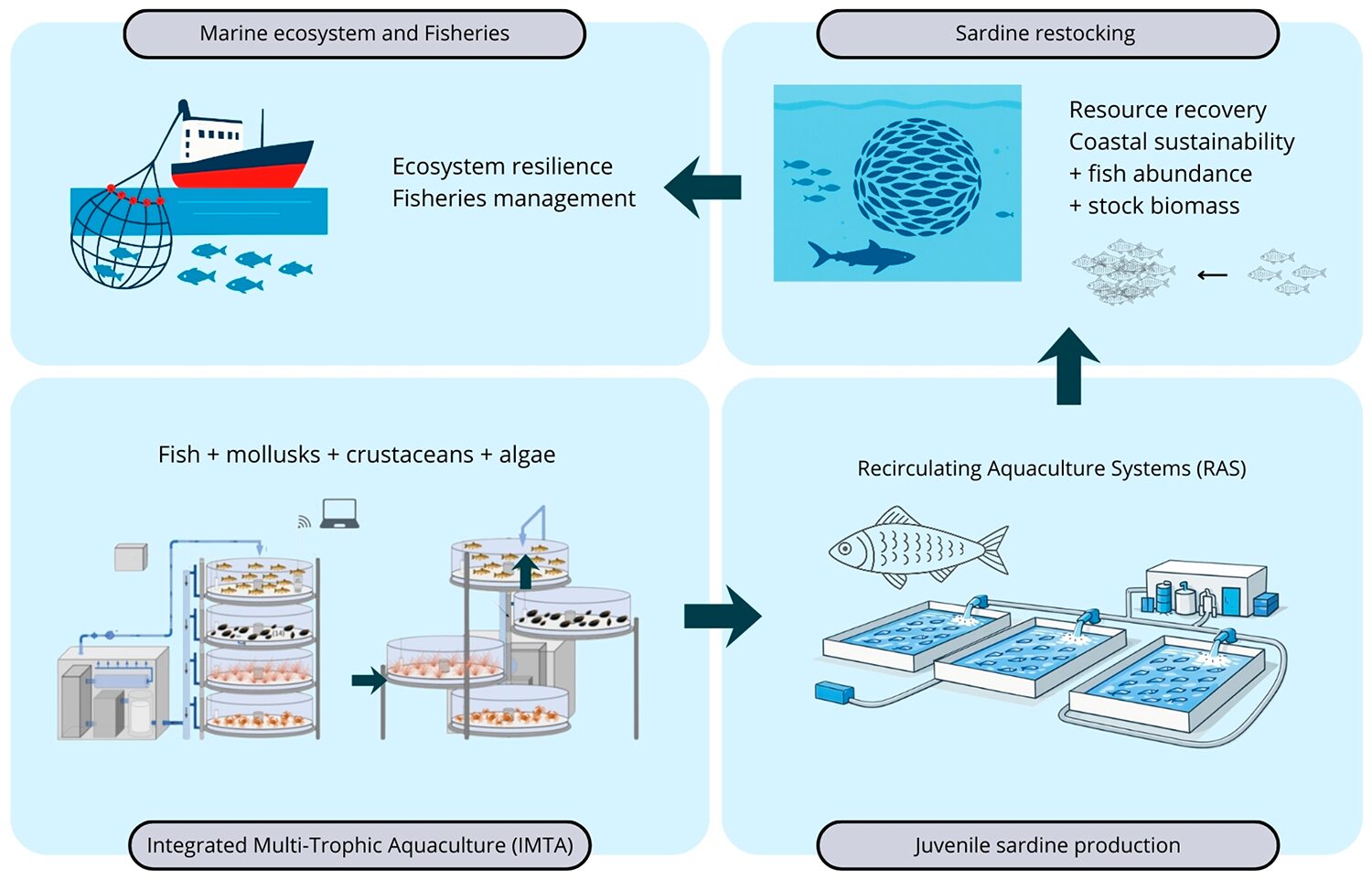

This article by Angel Urzúa and co-workers presents a perspective on the potential for producing juvenile common sardines (Strangomera bentincki) in land-based Ecological Aquaculture (EA) systems as a strategy to address overexploitation and environmental pressures on wild stocks. The study synthesizes existing literature from 82 references on fisheries dynamics, climate impacts, and aquaculture technologies, and integrates ecological insights with biotechnological advancements to propose sustainable alternatives for restocking and coastal ecosystem resilience.

The authors emphasize the global significance of small pelagic fishes like sardines, which are crucial for fisheries, aquaculture feeds, and marine food webs. Specifically, S. bentincki, endemic to the Humboldt Current System off Chile’s coast, supports industrial and artisanal fisheries with projected annual landings of 300,000 tons by 2025, primarily for fishmeal production.

As a keystone species, it occupies an intermediate trophic level, feeding on plankton and serving as prey for predators like fish, cephalopods, marine mammals, and seabirds. However, overfishing and climate-induced variability – such as marine heatwaves – threaten sardine populations by disrupting the early-life stages (eggs, larvae, juveniles) through mismatches in predator-prey timing and reduced plankton availability, as per Cushing’s match-mismatch theory.

Authors describe in detail the life cycle of S. bentincki from eggs to yolk-sac larvae, first-feeding larvae, juveniles, and adults, with winter spawning and recruitment 4-5 months later. The species exhibits rapid growth, early maturity (130-150 mm within the first year), and a partial capital-breeding strategy with two spawning periods tied to seasonal upwelling. Climate change exacerbates vulnerabilities, potentially altering phenology, nutritional quality, and reproductive success, and the study argues for diversifying aquaculture beyond monocultures like salmonids, advocating for native species cultivation to bolster resilience.

The study’s main discussion is centered on the use of EA systems, including Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) and Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). RAS provides controlled environments with biofilters, UV sterilization, and precise management of temperature, feeding, and water quality, ideal for studying larval survival, growth, and physiological responses. IMTA, by contrast, mimics natural ecosystems through multi-species integration across trophic levels, enabling nutrient recycling and minimizing environmental impacts like eutrophication.

These systems facilitate year-round production, reduce reliance on wild catches, and support investigations into fatty acid metabolism, particularly highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). These lipids are vital for somatic growth, reproduction, thermal tolerance, and the adaptation of membranes’ fluidity to temperature fluctuations.

Authors also highlight how ocean warming may diminish HUFA availability in food webs, affecting sardine quality and aquaculture feeds, and discuss challenges in sardine culture, such as cannibalism, high larval mortality, and specific nutritional needs; and propose standardized protocols to bridge knowledge gaps in husbandry (e.g., temperature thresholds, nutrient densities, growth rates).

Relevance of research findings to the industry

The findings of this study could have important significance for the fisheries and aquaculture industries, particularly in regions like Chile where S. bentincki drives economic activity. Juvenile production of sardines and similar species in EA systems for restocking offers a pathway to alleviate overexploitation, with global small pelagic catches exceeding millions of tons annually and many stocks declining.

For the fishmeal industry, which relies heavily on sardines for aquaculture feeds, controlled production could ensure stable supply chains, reducing dependency on volatile wild harvests influenced by environmental variability. Globally, this model could be adapted for other sardine species (e.g., in Peru or Europe), fostering innovation in ecological engineering and contributing to food security.

Perspectives

Looking forward, the authors believe that EA systems could be transformative for sardine management under escalating climate pressures. Future research should prioritize empirical trials to validate protocols, such as optimizing thermal regimes (e.g., 15-20 degrees-C for larvae) and HUFA-enriched diets to boost survival rates above 50 percent.

Broader perspectives also discussed include policy integration, urging governments to incentivize restocking programs through subsidies or regulations, similar to Japan’s successful sardine enhancements. Challenges remain, like high initial costs for RAS setups, but long-term benefits in resilience and sustainability outweigh them. Ultimately, this interdisciplinary framework could support strategies to promote and enhance sardine fisheries within current global changes.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Darryl Jory, Ph.D.

Editor Emeritus

[103,114,111,46,100,111,111,102,97,101,115,108,97,98,111,108,103,64,121,114,111,106,46,108,121,114,114,97,100]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Aquafeeds

Fortifying shellfish with novel microencapsulated feeds could help address human nutrient deficiencies

Evaluating a novel microencapsulated feed supplied during the depuration stage to fortify oysters with micronutrients beneficial to human health.

Aquafeeds

‘We will very likely find it’: Microplastics warning sounded for aquafeeds

The warning about microplastics pollution is finding its way to aquaculture, as a new study finds contaminated samples of fishmeal, a prominent aquafeeds ingredient.

Responsibility

California shellfish farmers need greater support to face effects of climate change, OSU study finds

A new study found California shellfish farmers need improved access to data and stronger connections to adapt to the effects of climate change.

Health & Welfare

‘The right thing to do’: How aquaculture is innovating to reduce fish stress and improve animal welfare

With research showing that stress can damage meat quality, fish and shrimp farmers are weighing the latest animal welfare solutions.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)