China continues to face several emerging challenges in improving the management of its pelagic tuna fisheries

The pelagic tuna fishery (PTF) is a crucial component of China’s pelagic fisheries. Its rapid and efficient development can be attributed to its management framework, which not only provides support but also exercises supervision over the development of PTF by ratifying international instruments, participating in the tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), enacting a comprehensive set of domestic regulations and policies, and implementing various management measures.

A significant body of literature has explored the evolution of China’s PF management. However, these studies have not specifically concentrated on the management of China’s PTF, nor have they analyzed the emerging challenges faced by PTF management or offered corresponding recommendations.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Chu, X-L. 2025. Exploring the management of the pelagic tuna fisheries in China: Evolution, challenges and recommendations. Fisheries Research Volume 291, November 2025, 107550) – discusses a study that analyzed the current challenges associated with the management of pelagic tuna fisheries (PTF) in China by examining its evolution and provides recommendations for improvement.

The data and government documents utilized in this study were sourced from the official websites of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) in China, as well as from the China’s Fishery Statistical Yearbooks from 1986 to 2023, published by China Agriculture Publishing House, encompassing the years 1986–2023. The data pertaining to tuna catch and fishing vessels are widely acknowledged to possess inherent potential inaccuracies, as highlighted in prior research. Nonetheless, these datasets represent the most comprehensive temporal and spatial information available for the purposes of our study.

Pelagic tuna operations of China

In 1988, China’s PTF began operations by acquiring its first fishing vessel from Japan. Subsequently, additional second-hand PTF vessels were procured from Japan and South Korea, thereby facilitating the advancement of the sector during its early stages.

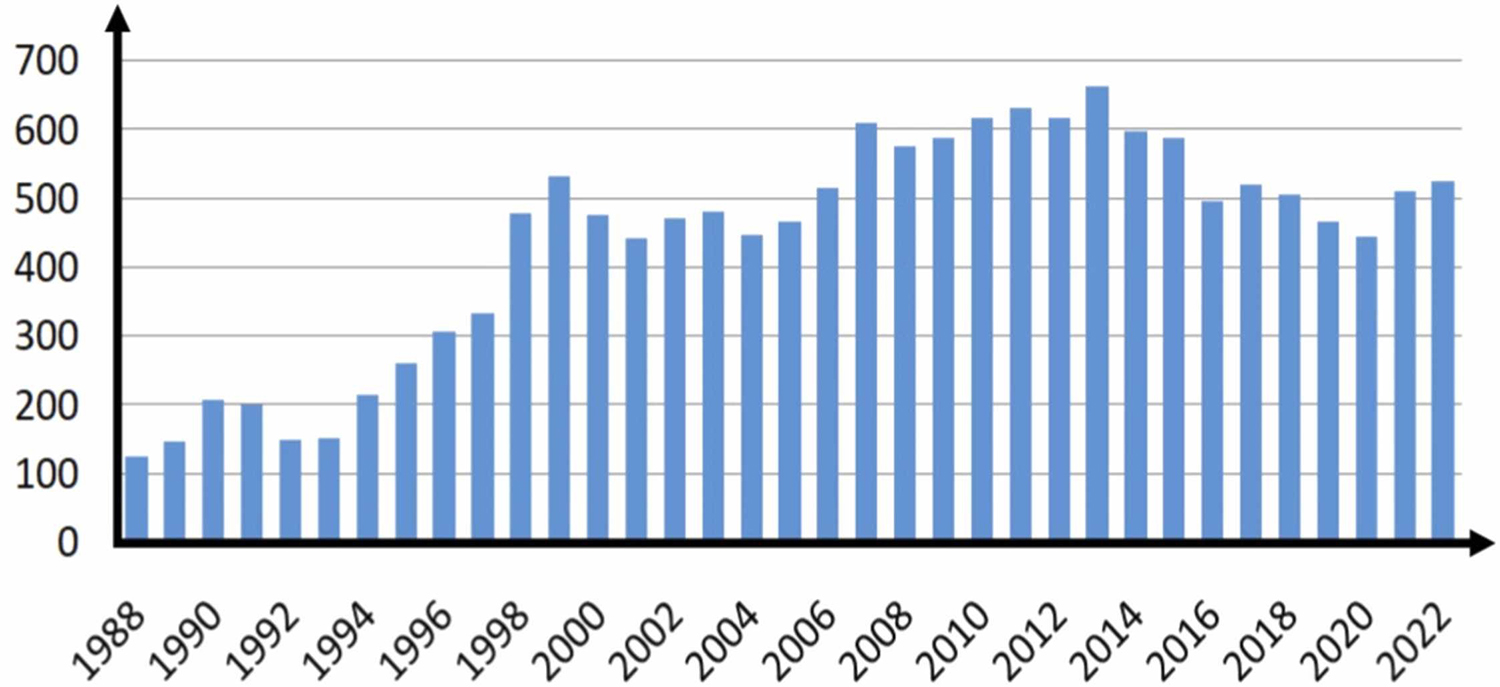

The Chinese Central Government prioritized the development of PTF by implementing a range of supportive policies, and in 2006, fuel subsidies were introduced to alleviate the substantial costs incurred during fishing operations. In the following years, these subsidies were significantly increased, spurring a construction boom in PTF vessels. Currently, the PTF operations are predominantly categorized into two main types: those conducted within the EEZs of other coastal states and those undertaken in the high seas. The former is contingent upon the establishment of bilateral fishing cooperation agreements, whereas the latter is governed by the tuna RFMOs.

The fishing methodologies employed by the PTF primarily encompass longline fishing and purse seine fishing. For tuna longline fishing, three distinct categories are identified regarding refrigeration of the fish caught: normal temperature, ice fresh and ultra-low refrigerated. For example, in the western and central Pacific Ocean, vessels utilizing ultra-low refrigerated long-line techniques predominantly operate in the high seas, primarily targeting big eye tuna. In contrast, normal temperature long-line fishing vessels typically operate either in the high seas or within the EEZs of island nations, targeting albacore tuna. Regarding tuna purse seine fishing, the majority of vessels from China are active in the high seas of Western and Central Pacific Ocean, as well as within the EEZs of island nations such as Micronesia and Papua New Guinea.

In 2023, the annual production of China’s PTF reached 395,000 tons, supported by 49 enterprises and 486 vessels. This output constituted 17 percent of the nation’s total production by pelagic fisheries. Between 1950 and 2019, China was ranked 19th globally, contributing a mere 1 percent to the total tuna catch worldwide. Additionally, in 2023 China’s exports of canned tuna reached 139,100 tons with a total value of U.S. $832 million. The export value not only contributed to the growth of the PTF industry but also positively impacted various related sectors, including fish processing equipment manufacturing, vessel maintenance, and shipbuilding. In 2023, these ancillary industries collectively generated an additional revenue of $232.1 billion and created thousands of job opportunities.

Shortage of crew members

Chinese pelagic tuna fishing enterprises face a severe crew shortage as coastal workers increasingly avoid the profession due to its harsh conditions and low pay. The average annual income for PTF crew members is only $6,944 to $8,333, roughly half that of coastal residents, prompting many to seek safer, better-paid jobs ashore.

To address the labor shortfall, PTF companies have turned to recruiting inland Chinese workers and foreign crews, mainly through intermediary agencies. Inland recruits often lack fishing skills and frequently breach contracts, disrupting operations. Foreign crew recruitment suffers from poor oversight, with workers typically transferred via third countries without required medical checks or training. Labor disputes, especially with foreign workers, are complicated by indirect communication through agencies and potential diplomatic sensitivities, while domestic inland worker disputes often involve non-standard contracts and weak management practices.

Impact of climate change and economic development on the catches of small pelagic fisheries

Inefficient industrial structure

Most Chinese PTF enterprises remain caught in the primary production stage, heavily dependent on government subsidies, with only a few having built complete industry chains. Fuel subsidies, introduced in 2006, grew nearly tenfold from $390 million to $3.722 billion by 2017. Even after the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) reformed the policy in 2021 to target only enterprises meeting international conservation standards, subsidies remain a major profit source due to weak industrial chains and low competitiveness. Long-term over-reliance on international markets, while neglecting domestic ones, has left Chinese-caught tuna prices highly vulnerable to external influences.

Based on the experiences of other fishery nations, it is evident that pelagic refrigerated transportation can enhance fish product value by 20–50 percent, while refined processing of the fish has the potential to double the product’s value, resulting in an increase of as much as 100 percent.

Ineffectiveness of the MCS system

The Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) system implemented for China’s PTF demonstrates limited efficacy and practicality. The ineffectiveness of the MCS framework can be primarily attributed to a shortage of enforcement personnel and the inadequacy of existing regulations. Specifically, the management of the PTF in China is under the jurisdiction of the Fishery Administration Bureau (FAB), a bureau-level agency within the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA). Unlike certain countries where a ministerial-level department oversees PTF management, the FAB functions at a subordinate hierarchical level and is limited by insufficient personnel resources.

As a result, this organizational structure has led to a reliance on passive oversight rather than proactive, real-time monitoring. In response to these challenges, the FAB established the China Overseas Fisheries Association (COFA) in 2012 to support PTF management. While this initiative has alleviated some of the management pressures faced by the FAB and has contributed to the improvement of self-regulation within the industry, it has not fundamentally resolved the underlying issues.

In relation to the inadequacy in current regulations, a significant example of this issue can be observed in administrative regulations and policies governing observers. The existing documentation lacks a clear delineation of the responsibilities and rights of observers, resulting in ambiguities regarding their duties and obstructing their access to obtain timely protection in cases of violations of rights.

Perspectives

China has implemented four aspects of management measures to supervise the PTF, which include regulating fishing capacity, collecting and reporting fishing data, implementing an MCS system, and enhancing by-catch management. Nonetheless, China continues to face several emerging challenges in improving its PTF management, including a significant shortage of crew members, an inefficient industrial structure, the ineffectiveness of the MCS system, and other issues. It is advisable to standardize the management of foreign crews, establish a comprehensive industry chain, intensify scientific research, and improve crew training, as well as to enhance the effectiveness of the MCS system in order to strengthen its future PTF management.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Xiao-lin Chu

Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China

[110,99,46,117,100,101,46,117,111,104,115,64,117,104,99,108,120]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

A review of bycatch in the Antarctic krill trawl fishery

Understanding the significance of bycatch is critical to managing Antarctic krill, a keystone species and the largest fishery in the Southern Ocean.

Health & Welfare

Achotines laboratory home to continuing studies of tuna early life history

The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission Achotines Laboratory in southern Panama is the world’s only facility with nearly year-round availability of tuna eggs and larvae. A study is comparing the reproductive biology, genetics and early life history of yellowfin and Pacific bluefin tuna.

Fisheries

‘A world down below’ – Deeper fishing insights lead to better tools for bycatch reduction

High-tech bycatch reduction devices – data analytics, cameras and sensors – are in play but SafetyNet Technologies says the secret is collaboration.

Fisheries

Can repurposing fish aggregating devices make MPAs more effective?

A new study suggests that fish aggregating devices could be repurposed to enhance marine protected areas (MPAs).