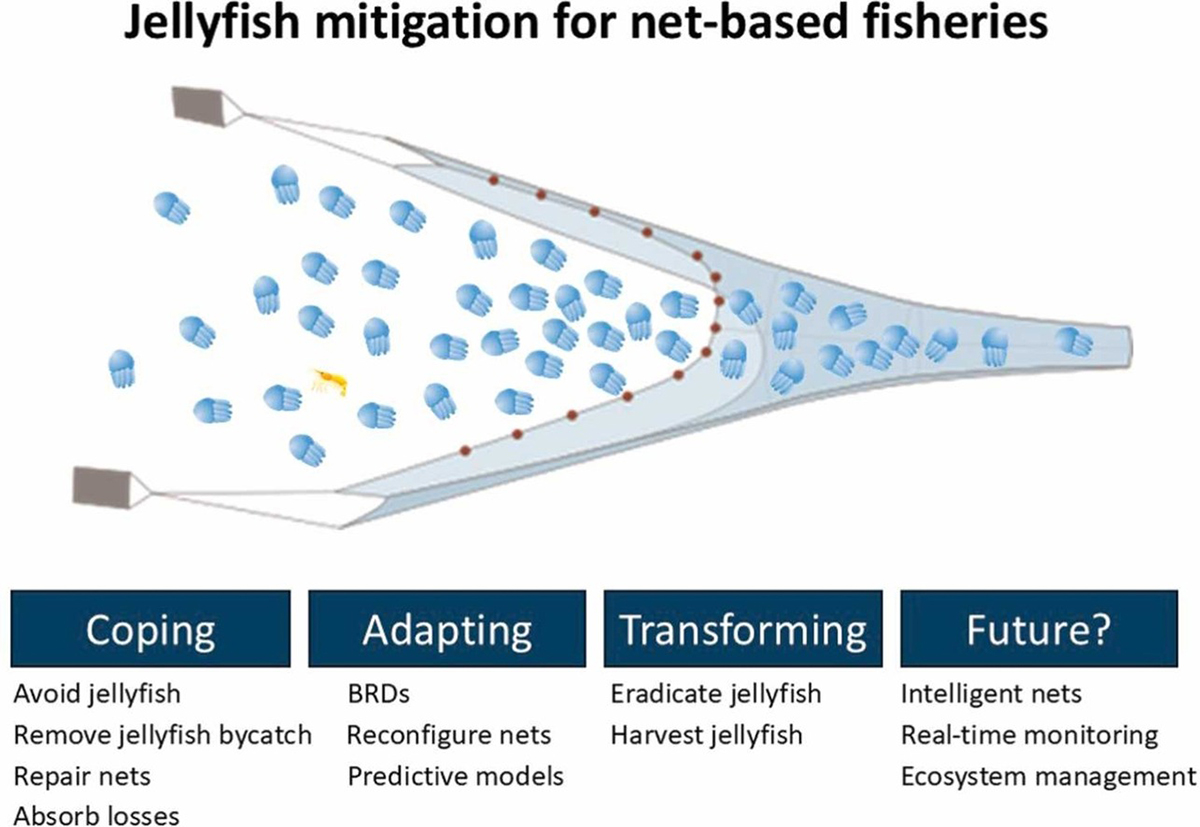

Net-based fisheries use multi-faceted approaches, including coping, adapting and transforming strategies to mitigate jellyfish but the methods used have remained largely unchanged for decades

Jellyfish are a natural and essential component of healthy marine ecosystems and provide important ecosystem services, including prey and providing a refuge and habitat for juvenile fish and invertebrates, including some commercially important species. Jellyfish populations are renowned for forming spectacular blooms that can be hazardous and costly for coastal industries, including net-based fisheries.

When caught in large numbers, the sheer weight of the jellyfish bycatch places enormous stress on fishing gear and occasionally trawlers have capsized after their nets have snagged large blooms of jellyfish. Jellyfish trapped alongside fish in the net, may sting or injure the fish. Injured fish are less appealing to consumers and attract lower prices or may be discarded. The stings of jellyfish also increase mortality of discard from trawls, seines and gillnets, and pose health risks to fishers.

The economic losses caused by jellyfish can be devastating for the commercial fishers directly affected, and the supply chain that supports the fishing industry. For example, processing plants may work at reduced capacity or be left idle, and wholesalers and retailers may be unable to access fish to sell. Estimates of the economic costs of jellyfish on commercial fisheries are scarce but fisheries in Japan and Korea have reported annual losses of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Most jellyfish blooms are transient events that pose short-term challenges to fishers. However, in some regions, some jellyfish species form more persistent and expansive blooms, and introductions of non-native jellyfish species and range expansions may pose new challenges to fishers. In these situations, fishers need to adapt or transform their industries to remain viable.

The impacts of jellyfish on commercial fisheries have been recently reviewed but there remains a critical gap in the literature about the practical, evidence-based strategies available to commercial fishers to manage interactions with jellyfish. Moreover, there has been no comprehensive assessment of how emerging technologies, such as computer vision and drones, and ecosystem-based management approaches could be leveraged to reduce jellyfish-fishery interactions. Addressing this gap is essential to equip stakeholders with the tools and knowledge needed to build resilience in fisheries that face frequent and severe jellyfish disruptions.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Pitt, K.A. et al. 2025. Jellyfish mitigation for net-based fisheries: A qualitative systematic review. Fisheries Research Volume 291, November 2025, 107535) – reports on a study that reviewed existing strategies and proposes novel methods for mitigating jellyfish for net-based fisheries.

First, we systematically searched the scientific and grey literature to identify studies focusing on jellyfish mitigation for fisheries. We then applied knowledge of jellyfish ecology and explored technological innovations to propose novel methods that could be trialed or implemented by net-based fisheries to mitigate jellyfish.

Existing methods used by fishers to mitigate jellyfish

Our systematic search of the literature identified 35 papers that discussed methods net-based fishers use to mitigate jellyfish. Of these, ten papers referred to coping strategies, twenty-two referred to adaptive strategies, and six discussed transformative strategies (some papers referred to more than one category).

Coping strategies

When jellyfish occur in relatively small numbers or when blooms are short-lived, fishers implement a variety of strategies to cope with the immediate problems posed by jellyfish. Coping strategies include relocating vessels to avoid jellyfish, manually removing jellyfish bycatch from nets, repairing nets and fishing gear damaged by jellyfish, reducing the duration of trawls or, if permits allow, temporarily using different fishing gear (such as anchored gillnets and drift nets) that are less impacted by jellyfish.

All these coping strategies incur costs that are absorbed by the fishers and reduce their income. Relocating vessels to avoid jellyfish may use more fuel and reduce the time available for fishing, and catches may be reduced if jellyfish prevent fishers from operating in prime fishing grounds. Some fishers reported fishing for longer to compensate for lost fishing time. Coping strategies have also been implemented by the supply chain, including fish processing plants, but catches contaminated with jellyfish are more difficult for factories to process and generate additional waste.

Adapting strategies

When jellyfish blooms occur regularly, persist for longer, or are widespread, coping strategies are inadequate and fishing industries adapt to the regular presence of jellyfish to ensure their on-going viability. Of the twenty-two papers that referred to adaptation strategies, sixteen discussed bycatch reduction devices (BRDs), two discussed reconfiguring nets, one referred to adding a cutting device to nets, two discussed using predictive models to provide advanced warning of jellyfish blooms and one focused on real-time monitoring.

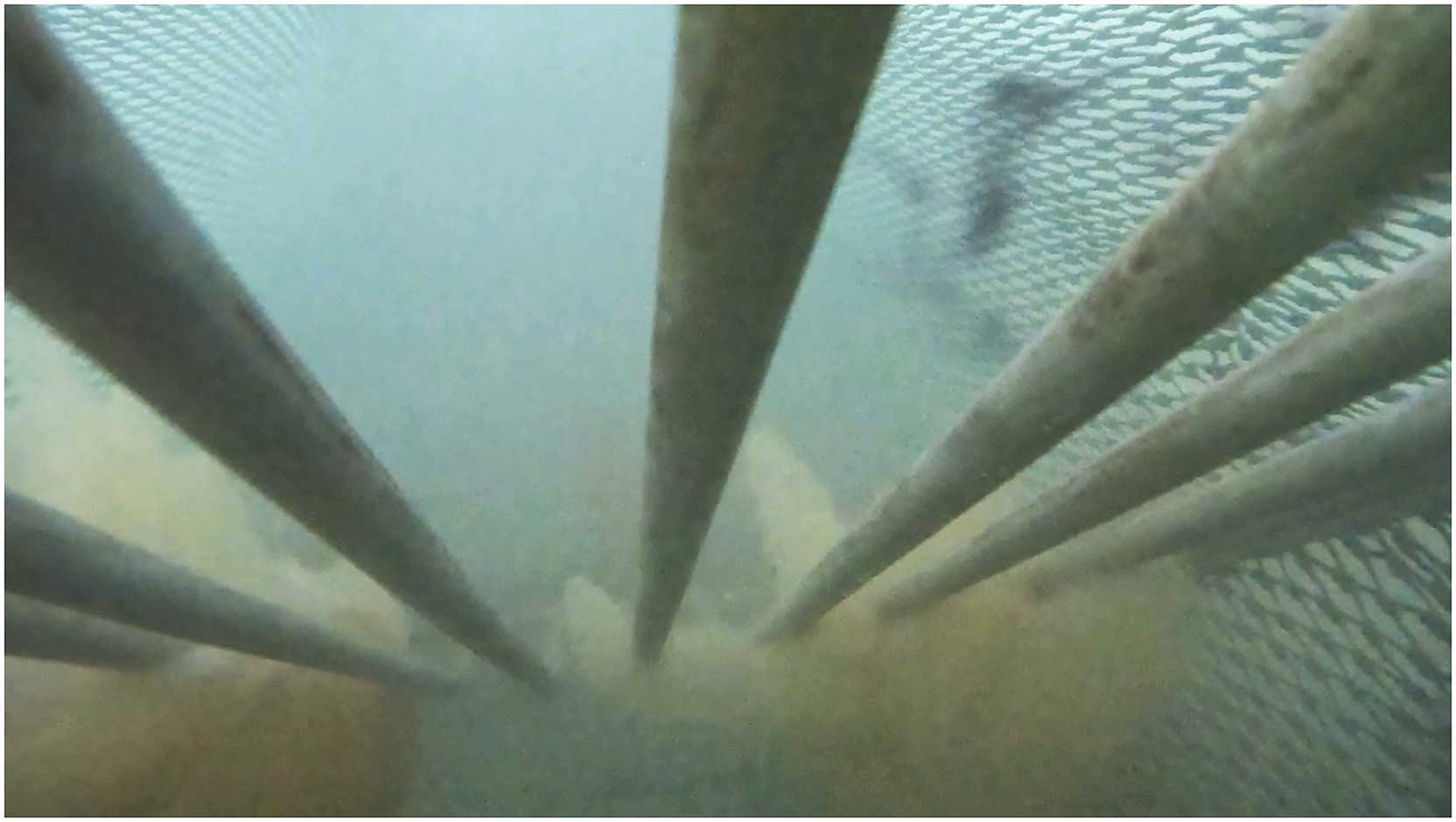

BRDs are the main tool used by trawl fisheries to reduce bycatch of jellyfish. BRDs for jellyfish consist of mesh panels or funnels, or rigid grids inserted into the net, in front of the cod-end. Commercially targeted species, that are smaller than the BRD’s mesh size or grid spacing, pass through the BRD while jellyfish, which are larger, are deflected out of an opening in the net. Although numerous studies have optimized the efficiency of BRDs by altering the grid/mesh size and angle of placement, BRD technology to address jellyfish bycatch for trawls has not fundamentally changed in many decades.

Changes to the configuration of the trawls may also reduce jellyfish bycatches. In Brazil, fishers reported catching fewer jellyfish after they reduced the vertical opening of their nets, by either removing floats from the top panel, or tying the top and bottom panels together. Similar reductions in jellyfish bycatch were achieved in Australia where trawls targeting penaeid prawns usually have headline ropes and foot ropes of similar length. Jellyfish can also impact purse seine and fixed net fisheries.

Transforming strategies

Transforming strategies involve long-term, fundamental changes to the industry or environment, to ensure the viability of the socio-ecological system. At its most extreme, transforming involves fishers leaving the industry or the fishery closing altogether, but transformations also include reducing jellyfish populations and the fishing industry pivoting to harvesting jellyfish. Of the six papers identified that specifically referred to transformation strategies for fisheries, three referred to removing medusae using trawls or robots, one discussed eradicating polyps, and two referred to harvesting jellyfish. No literature discussed fishers leaving the industry or a fishery closing, although such incidents may not have been reported in the scientific or grey literature located by our search.

Relatively few attempts have been made to mitigate jellyfish by actively removing them from the environment, and no information about the success of these attempts to remove jellyfish is available but presumably the costs of using trawlers are high. Automated robots that shred jellyfish have also been trialed as a tool for removing jellyfish in South Korea. Jellyfish removal programs create large amounts of waste that can be problematic to dispose of.

Some jellyfish have been harvested for food and traditional medicine in China for over 1700 years. Growing demand for jellyfish as food, as sources of collagen and novel compounds with possible biotechnological and biomedical applications has seen fisheries for jellyfish expand into the Americas, Mediterranean, India and other countries. Although it has been suggested that fisheries severely impacted by jellyfish might pivot towards harvesting jellyfish, there is limited evidence that this has occurred, potentially because only a sub-set of jellyfish species are commercially valuable.

Guide shows commercial tuna fishers how to build net-free, biodegradable fish aggregating devices

Possible technological and ecosystem-based approaches to mitigating jellyfishes

Our review of the literature highlighted that, with the recent exception of numerical models to predict jellyfish blooms, commercial fishers mostly rely on mitigation methods (e.g. BRDs) that have remained largely unchanged for decades. Although some innovations, such as jellyfish shredding robots, have been trialed, they have not been adopted by the fishing industry, presumably because they are not feasible for large-scale removal of jellyfish. Rapid innovations in technology, sensors, modeling and improved understanding of jellyfish ecology, may offer some new ways to mitigate jellyfish.

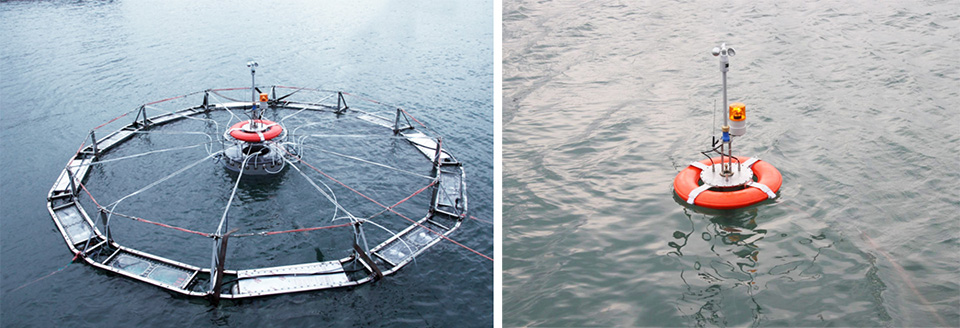

Computer vision is emerging as an important tool for monitoring the marine environment and could be used to reduce bycatch in trawl fisheries. Several research institutes are developing “intelligent nets” that use computer vision to monitor and manage bycatch. Computer vision models are being built to automatically detect target and non-target species and to close the codend when the number of unwanted species exceeds a threshold, and these computer vision models could be easily trained to detect jellyfish. While prototypes of intelligent nets have been tested, this emerging technology may only be suitable for use on large trawlers and afforded by wealthy fishing companies. As the technology is refined and adopted more widely, it may become affordable for small to medium sized fishing enterprises and the broader fishing community.

Technological advancements increase our ability to monitor jellyfish in real-time and could be used by fishers to avoid deploying nets in areas where jellyfish are abundant. Many jellyfish species are readily observed by drones, which could be flown ahead of a trawler at a distance that would provide sufficient lead-time to retrieve the net if jellyfish are observed. Drones are inexpensive and easily operated but only observe jellyfish near the surface and so may only be useful in shallow systems, such as coastal lagoons and when the water is relatively clear.

Jellyfish are also detectable by acoustic sounders, despite their bodies being a similar density to seawater and lacking swim bladders that reflect sound in fish. Sounders can detect jellyfish occurring throughout the water column, however, as they are mounted on the vessel, they are unlikely to provide sufficient lead-time to retrieve trawls when jellyfish are detected. Acoustics could be used prior to deploying nets, however, to determine whether jellyfish are present along the planned trawl path or in the general vicinity before nets are deployed. Since sounders are already used by most fishing vessels, they require no additional investment by the fisher, although monitoring the vicinity before nets are deployed takes time and resources. Acoustic monitoring of jellyfish, in real time and at large scales (i.e. across tens to hundreds of km) has been proposed via deployment of underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSNs).

Predictions of where and when jellyfish are likely to occur could enable fishers to avoid jellyfish or prepare for jellyfish encounters. Many jellyfish actively swim and move horizontally and vertically through the water column. Acoustic sounders, miniaturized tags and nets have also been used to assess vertical distributions of jellyfish and how they move in response to tides (i.e. tidal stream transport) or time of day (i.e. diel migration). However, evidence for coordinated mass vertical migrations of jellyfish populations is rare because individuals exhibit enormous variation in swimming speeds and depth excursions that outweigh population level responses. Relatively few species have been studied and estuarine jellyfish subject to strong tidal flows may be ideal candidates to test for evidence of tidal migrations.

Advances in underwater autonomous vehicles, tagging technologies and hydrodynamic modeling mean that it is becoming more feasible to track and predict movements in complex underwater environments. Building knowledge of where jellyfish occur and how their distributions change in relation to tides and/or time of day could enable fishers to identify places or times where they could safely deploy nets.

Jellyfish populations might be managed indirectly by manipulating environmental conditions or enhancing populations of their predators and competitors. Varying environmental flows in estuaries can impact jellyfish species, via sudden reductions in salinity which can kill medusae and polyps, or by altering hydrodynamics. Hence, sudden releases of freshwater (“freshets”) in bonded estuaries have been proposed to manage problematic jellyfish populations. Species vary considerably, however, in their salinity tolerances, and the success of this approach would depend greatly on the geomorphology of the estuary, as deep areas in the estuary may provide a salinity refuge for polyps from low salinity events. Importantly, the impacts on non-target species in the estuary, would need to be considered.

Medusae are eaten by diverse predators, so enhancing numbers of predators and competitors in the environment could limit abundances of jellyfish but relatively little is known about predator/prey dynamics and whether predators can regulate populations of polyps or medusae.

Perspectives

Net-based fisheries use multi-faceted approaches including coping, adapting, and transforming strategies to mitigate jellyfish but the methods used have remained largely unchanged for decades. Technological advancements, including computer vision, advanced tags, drones and acoustic techniques are beginning to offer innovative solutions. Some technologies, such as drones, are now affordable, but advanced solutions, such as intelligent nets, are likely to remain too expensive for small to medium sized fishing enterprises in the short-term. Ultimately, the long-term co-existence of net-based fisheries and jellyfish requires close cooperation among stakeholders, including fishers, managers and scientists.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Kylie A. Pitt

Corresponding author

School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, QLD 4222, Australia[117,97,46,117,100,101,46,104,116,105,102,102,105,114,103,64,116,116,105,80,46,75]

-

Claire Morrison

School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, QLD 4222, Australia

-

Iain M. Suthers

School of Biological, Earth, and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

-

Michael J. Kingsford

Marine Biology and Aquaculture, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4814, Australia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Automatic submersible fish cage systems counter weather, surface problems

The development of submersible fish cage technologies may be necessary to avoid the operational challenges of surface-based aquaculture, which can include extreme temperature and weather conditions, jellyfish infestation, oil spills and many types of biofouling.

Fisheries

‘A world down below’ – Deeper fishing insights lead to better tools for bycatch reduction

High-tech bycatch reduction devices – data analytics, cameras and sensors – are in play but SafetyNet Technologies says the secret is collaboration.

Fisheries

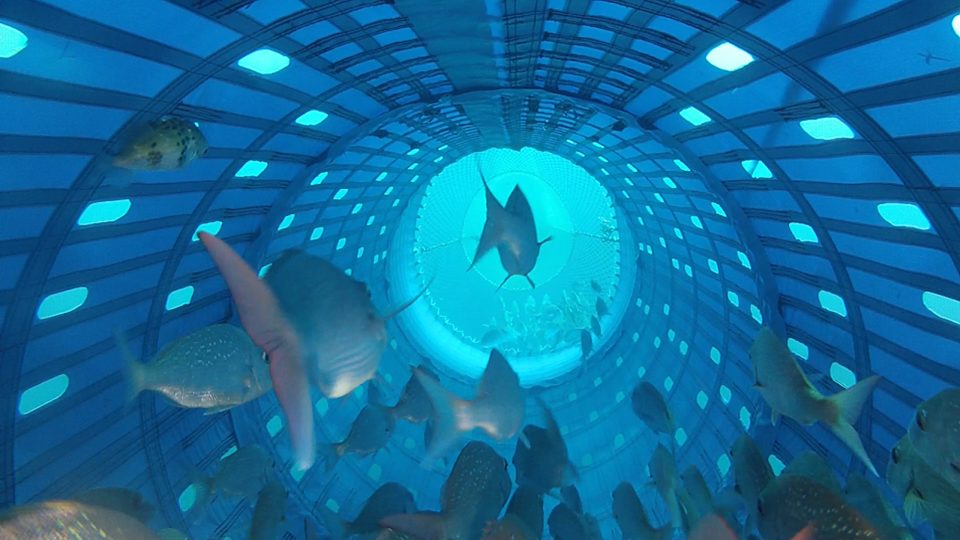

‘We were just looking for a way to fish better’: How one partnership is reinventing commercial fishing nets to reduce bycatch and improve animal welfare

Precision Seafood Harvesting’s novel reimagining of commercial fishing nets provides innovative solutions to both bycatch and animal welfare issues.

Fisheries

‘Here to stay and evolving fast’: How GreenFish’s AI-powered fish-forecasting tech is modernizing commercial fisheries

GreenFish uses AI and datasets to predict fishing hotspots, helping commercial fisheries save fuel, time and maximize catch value.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)