Results show widespread impact on both marine and terrestrial species

Nearly three-quarters of animal aquaculture relies on human-made feeds, composed of both marine- and terrestrial-derived ingredients. The production of raw materials used for aquafeed ingredients – shaped by their origins and production practices – constitutes the majority of aquaculture’s environmental footprint, accounting for between 57 and 94 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and other key pressures such as land and water use. Thus, improving the sustainability of aquafeeds represents a key lever for improving the environmental performance of aquaculture as a whole.

Biodiversity impact is a frequently missing component of feed sustainability assessments. Most existing evaluations focus on environmental pressures like land and water use, without directly assessing ecological outcomes. Various broader pressure-based assessments have provided valuable global overviews, but they stop short of linking pressures to species-level biodiversity outcomes. Understanding these impacts is increasingly important for industry. As standards for corporate sustainability reporting emerge, companies are under growing pressure to assess and disclose biodiversity risks.

At the same time, growing competition for feed resources across all animal sectors – including those for human food, fuel, and textiles – adds additional strain on the availability of raw materials for aquafeed. These challenges are likely to intensify as climate change increasingly impacts global supply chains and crop yields, further challenging efforts to ensure environmental sustainability of feed inputs. Robust biodiversity impact assessments – including analysis of habitat loss presented in this study – are therefore essential as the aquaculture sector continues to reduce dependence on wild-sourced fishmeal and fish oil (FMFO) and develops new feed materials and formulations.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Clawson, G. et al. 2025. Continued transitions from fish meal and oil in aquafeeds require close attention to habitat impact trade-offs. Cell Reports Sustainability 2, 100457 October 24, 2025) – presents the results of a study that assessed the biodiversity impacts, in the form of species habitat loss, on 54,628 marine and terrestrial species for two simplified but plausible Atlantic salmon feeds, presenting a new spatial approach to quantify the habitat loss associated with the production of animal feeds, using Atlantic salmon aquaculture as a case study.

Study setup

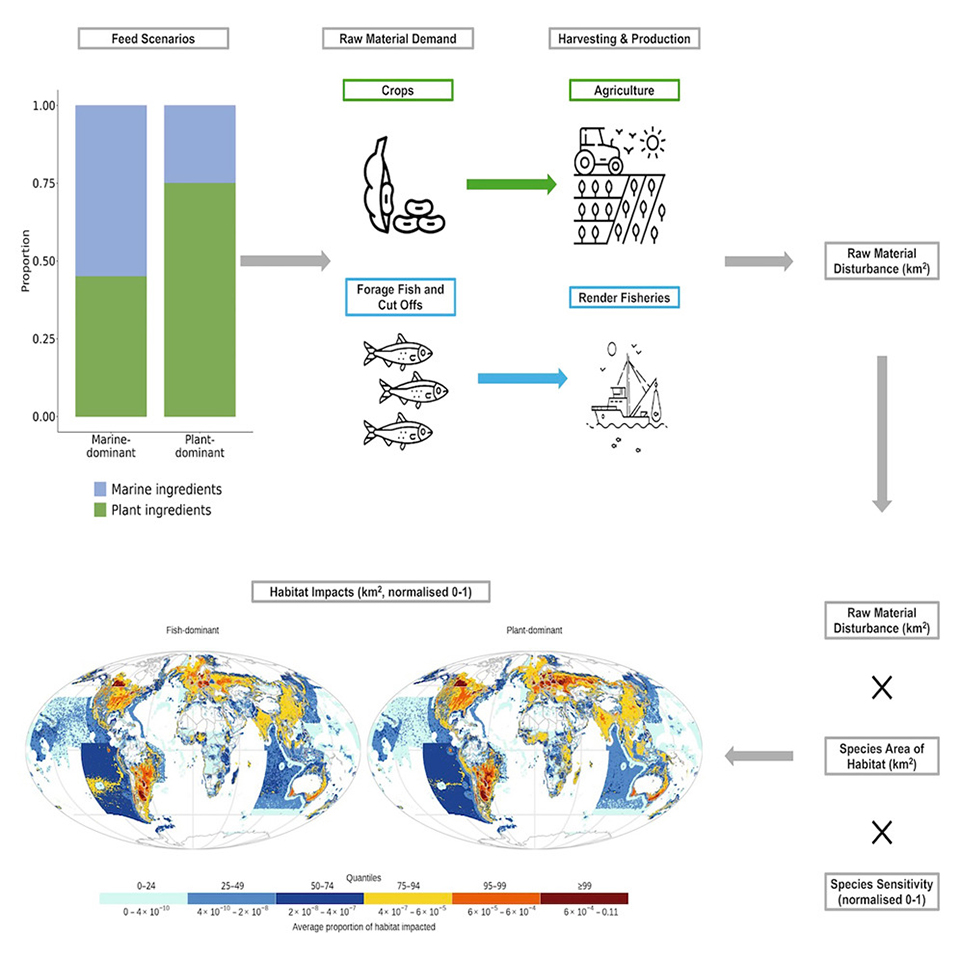

We conducted a spatial analysis to assess the habitat impacts of raw material production for salmon aquafeeds on 54,628 marine and terrestrial species. We mapped the spatial intersection of each species’ area of habitat (AOH) with disturbance pressures (i.e., land or ocean area used for raw material production, km2 equivalent) at 10 km resolution using the Mollweide equal-area projection. Overlapping areas (i.e., exposure), were weighed by sensitivity values for each species to assess impact. Species impacts within a location were averaged, regardless of their functional roles. Impact was measured as the proportion of each species’ habitat area affected in a pixel. All analyses were conducted using R statistical programming software version.

To estimate demand, we applied two feed formulations (plant-dominant and fish-dominant) to represent simple contrasts in formulation, with many plant-based ingredients being interchangeable. These formulations do not reflect the full range of possible salmon diets. They are derived from past and current feeds presented in literature, which are generalized from Norwegian salmon feed recipes.

For detailed information on the experimental design and data collection and analyses, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

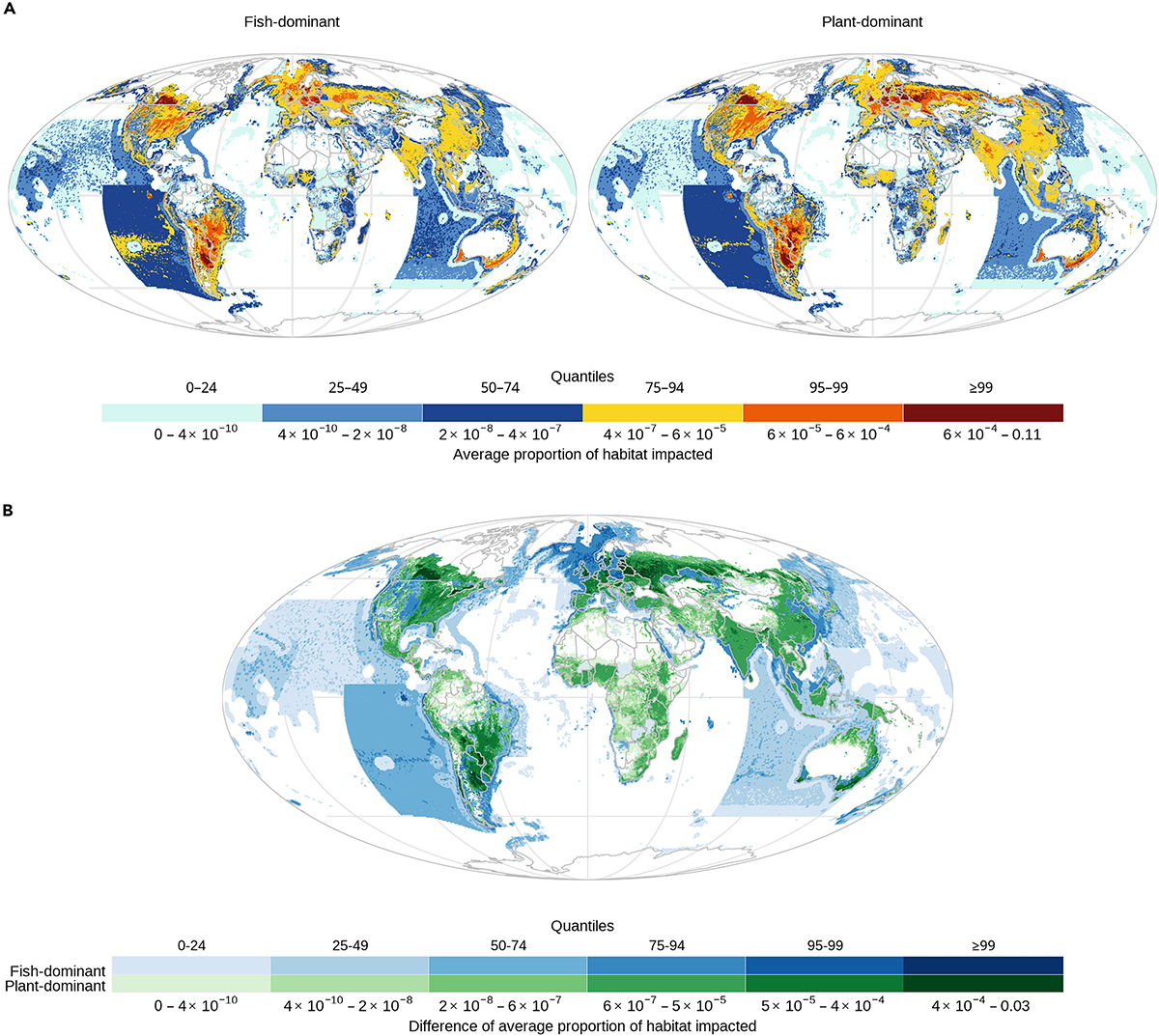

Our global map of mean proportion of habitat impacted reveals widespread but heterogeneous impacts from aquafeeds (Fig. 2A). We find that the majority of species assessed are impacted to some degree by raw material production for the fish-dominant or plant-dominant feeds (n = 42,471, 77.7 percent vs. n = 42,939, 78.6 percent, respectively). Across both scenarios, examples of “impact hotspots” (i.e., cells with impacts ≥95th quantile) are found in Northern and Eastern Europe, Chile, Canada, Brazil, Argentina and the European North Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 2A).

Additionally, we applied a rarity weighting on our impact metric, using each species’ global suitable habitat area as the weight, and we found strong agreement among identified hotspot areas. While impacts are spread across 231 countries, territories, and exclusive economic zones (EEZs), the mean proportion of species’ habitat impacted falls below 6 x 10−4 for 95 percent of impacted cells. As the aquaculture industry grows, hotspots represent important opportunities for reducing the environmental burden of feed production and achieving biodiversity targets.

Reducing FMFO dependence has been central to sustainable feed development for decades; however, our results complicate this narrative by suggesting that this shift may lead to trade-offs. Intuitively, the fish-dominant diet shows larger impacts across ocean pixels, particularly in high forage fish harvest areas like the North Atlantic, Humboldt, and East China Sea (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the plant-dominant diet generally has larger land impacts, notably in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Russia, and Canada (Fig. 2B). The plant-dominant feed impacts 37,760 km2 more habitat globally than the fish-dominant feed (552,924 vs. 515,164 km2, respectively).

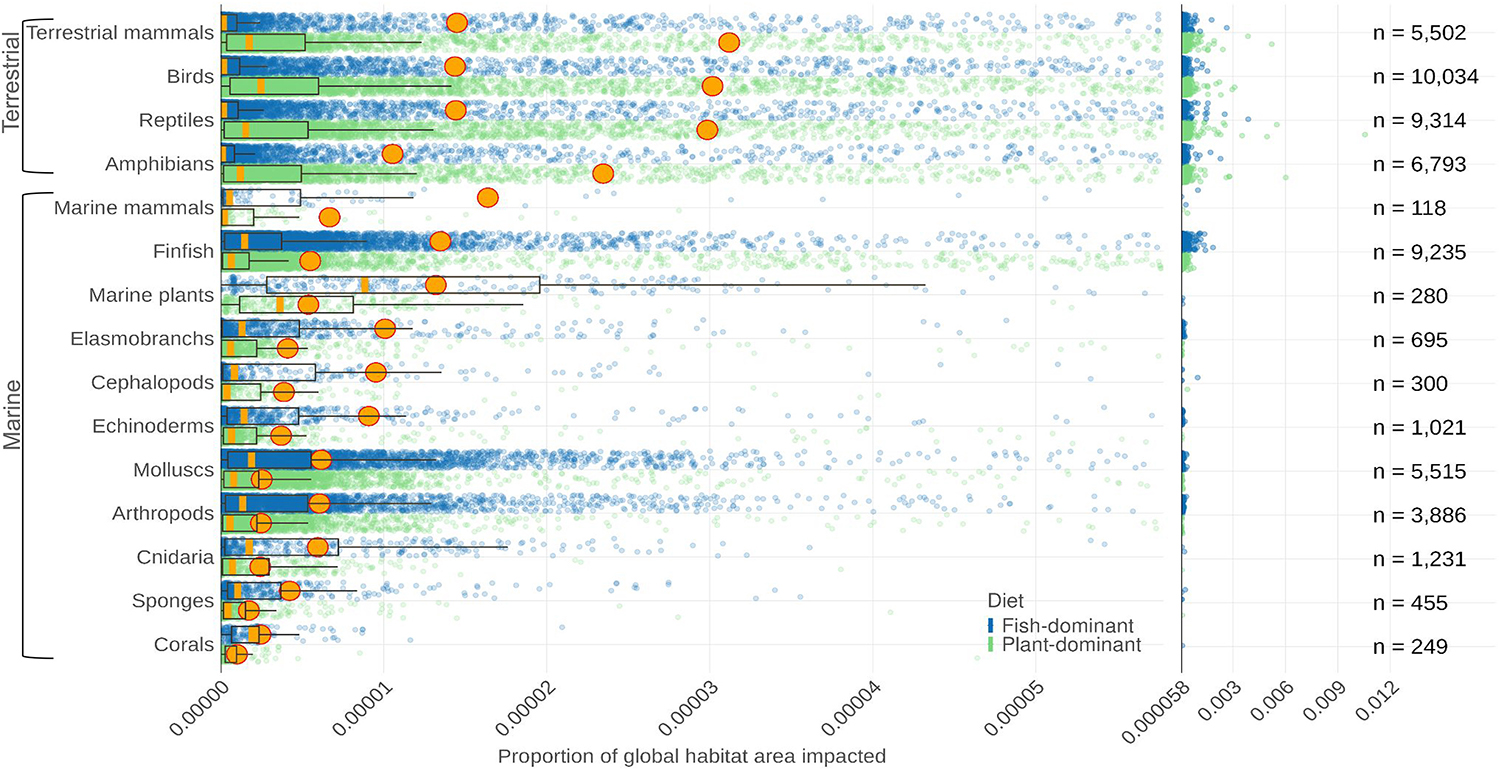

Additionally, the differences in the mean proportion of habitat impacted per cell are greater on land than in the ocean in either scenario. Average land impacts from the fish-dominant scenario are approximately 12.8 times greater than its ocean impacts, while the plant-dominant scenario’s land impacts are 36.7 times greater than its ocean impacts. The fish-dominant scenario has about 1.4 times greater average ocean impacts than the plant-dominant scenario, while the plant-dominant scenario impacts land habitats over twice as much as the fish-dominant scenario (∼2.04 times higher). Thus, overall, greater agricultural dependence for feed provisioning appears to have amplified impacts on terrestrial taxa.

Our results suggest that transitions from FMFO may have disproportionately shifted the biodiversity impacts of aquafeed production to terrestrial taxa. Aquaculture represents over half of the world’s aquatic animal production, and understanding how changes in aquafeed sourcing – particularly for key species like salmon – affect the spatial distribution of biodiversity impacts is crucial for addressing the global biodiversity crisis.

These methods and the findings of this study can guide the development of strategies to promote the sustainable growth of aquaculture while meeting biodiversity objectives. This methodology also lays the groundwork for future research into other food systems, as aquafeed impacts extend beyond salmon, and FMFO is increasingly replaced by similar agricultural ingredients in various animal feeds. To date, no other spatially explicit global biodiversity assessment of animal feeds exists, and we provide a new approach for examining these impacts.

Historically, shifts away from wild-sourced FMFO have been seen as key to sustainability. While previous studies have identified that marine ingredients typically exert lower midpoint impacts (i.e., pressures), our findings are novel because they calculate impact rather than pressures. We find average and total impacts are higher under a plant-dominant than a fish-dominant feed scenario, with terrestrial taxa generally more heavily impacted than marine species. This distinction underscores the importance of critically evaluating ingredients in aquafeeds, as continued shifts from FMFO may not guarantee better biodiversity outcomes.

Moving forward, increasing both aquafeed production from byproducts (e.g., fish trimmings, bacterial protein, insects fed on food waste) and continued shifts to plant-dominant diets (with increased scrutiny of the ingredient sourcing) will be essential to curb biodiversity impacts. Our results aim to highlight areas where the feed sector can improve sourcing and formulation. Ultimately, a combination of responsible sourcing and formulation will likely produce the largest benefit.

Our methods present an important conceptual advance in understanding how animal feed composition can alter biodiversity footprints. However, there are several important caveats to note. We use a simplified global diet for salmon farming, but in practice, feed compositions vary considerably between producers and depend on pricing and availability throughout a production year, potentially leading to different patterns of impact. The resolution of trade data affects our findings, as producer, distributor, and processor countries are inferred from trade links and crop production – for example, a country may appear to produce wheat products when it actually exports wheat gluten made from imported wheat.

Feed ingredients may not always be accurately reflected in trade classifications, especially for wheat- and pulse-derived materials, which can vary in specificity. Biodiversity data have observational biases, and these biases can be propagated through analyses. Nonetheless, the data we use represent the best-available information for a global analysis. Feed manufacturers should have access to finer-resolution production data, and they could use our methodology to rectify some of these limitations or use our results to flag areas that warrant further investigation. Our findings and methodology provide a foundation to support compliance with both mandatory and evolving biodiversity reporting standards.

Although the impacts identified by our analysis appear modest in scale, they are important for two reasons. First, they are almost certainly cumulative with impacts from other agriculture and fisheries that are not included in our analysis. These global food systems are major drivers of habitat loss and biodiversity decline. Second, this work was undertaken for current species habitat distributions, current feed layers, and current trade patterns. Into the future, distributions will change, and demand will grow as the world looks to feed billions more people.

Having a standardized and integrative approach to assess effects and potentially forecast them so alternative decisions can be made is an important tool to have. The adoption of this framework in other food systems could foster a broader understanding of the relationships between production choices and biodiversity outcomes, contributing to sustainable and environmentally conscious practices across the global food system.

Perspectives

This study assessed biodiversity impacts, in the form of species habitat loss, on 54,628 marine and terrestrial species for two simplified but plausible Atlantic salmon feeds. Results found widespread impact on both marine (∼89 percent) and terrestrial (∼71 percent) species, although the average magnitude of impact is small. Despite minimizing wild-sourced fishmeal and oil by necessity, increased agricultural dependence for feed provisioning appears to have disproportionately increased impacts on terrestrial taxa. The results provide key information for sourcing aquafeed to minimize impacts and optimize sustainability. As the aquaculture industry expands to feed billions more, a standardized approach to assess the effects of feed on global biodiversity is essential for informed decision-making.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Gage Clawson

Corresponding author

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia[117,97,46,117,100,101,46,115,97,116,117,64,110,111,115,119,97,108,99,46,101,103,97,103]

-

Julia L. Blanchard

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

-

Marceau Cormery

BioMar Group, Vaerkmestergade 25, 6th floor, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark

-

Elizabeth A. Fulton

Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

-

Benjamin S. Halpern

National Center for Ecological Analysis, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

-

Helen A. Hamilton

BioMar Group, Vaerkmestergade 25, 6th floor, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark

-

Casey C. O’Hara

National Center for Ecological Analysis, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

-

Richard S. Cottrell

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

EDF’s Rod Fujita discusses offshore aquaculture opportunities and potential pitfalls

Rod Fujita of Environmental Defense Fund discusses new offshore aquaculture research and what missteps a 'nascent' U.S. industry must avoid.

Responsibility

Conscious coupling: Can IMTA gain a foothold in Europe?

Integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) isn’t widely practiced in Europe but new findings indicate that farming multiple species on one site can work.

Aquafeeds

Point: There are no essential ingredients in aquaculture feeds

Kevin Fitzsimmons, leader of the F3 (fish-free feed) Challenge, says aquaculture may currently depend on fishmeal and fish oil, but farmed fish do not.

Aquafeeds

Counterpoint: Marine ingredients are stable in volume, strategic in aquaculture nutrition

IFFO Director General Petter M. Johannessen says fishmeal and fish oil offer unmatched nutrition and benefits to fuel aquaculture’s growth trajectory.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)