Tracking submerged aquatic vegetation extent revealed significant effects of habitat on lobster recruitment for several locations on the mid-western coast of Australia

In addition to the impacts of long-term climatic warming, extreme climate events like marine heatwaves (MHWs; extensive, persistent and extreme ocean temperature events), can adversely affect coastal ecosystems, including marine invertebrates and primary producers such as submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). Under climate change predictions, MHWs are expected to increase in frequency and extent, leading to increased impacts on submerged vegetation extent and cascading effects on marine ecosystems.

Climate-mediated alterations to critical marine habitats, such as SAV, are hypothesized to have flow-on effects on mammals, fishes and invertebrate assemblages. However, the indirect climate-mediated impact of habitat change on recruitment in invertebrate fisheries has not been systematically quantified across decadal timescales or at regional geographic scales. Despite the relatively recent advent and accessibility of remote sensing imagery, tracking critical fishery habitats across time is challenging and requires historical and standardized marine habitat indices for robust estimates.

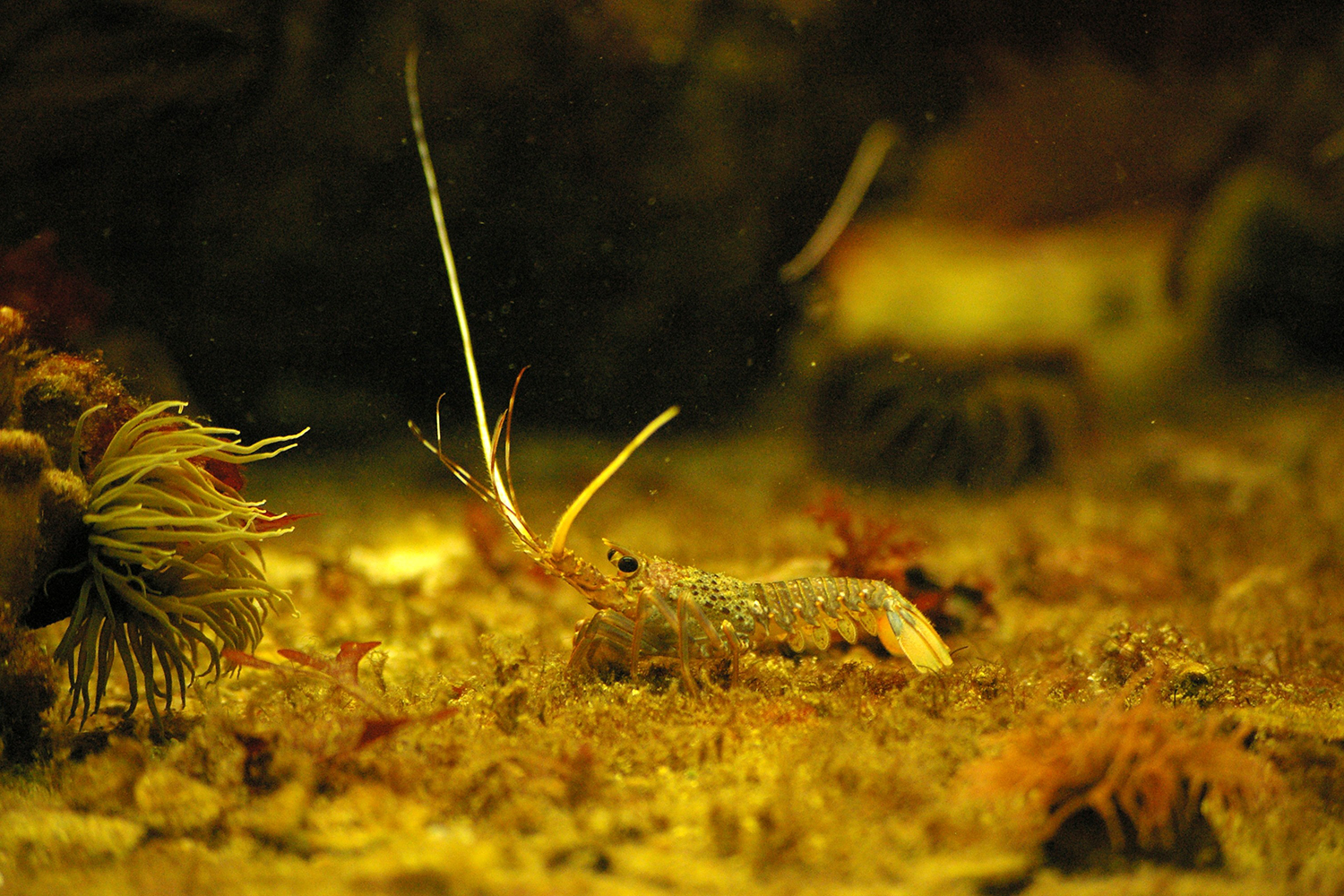

The West Coast Rock Lobster Managed Fishery (WCRLMF) is Australia’s most valuable single-species fishery, solely focused on the Western rock lobster (WRL, Panulirus cygnus), and is internationally recognized for its sustainable management practices. Since the 1960s, management of the WCRMLF has been informed by postlarval (puerulus, juvenile lobster) settlement indices (PIs) derived from artificial seagrass stations that are monitored lunar-monthly at eight coastal locations across the main geographical range of the species.

The influence of the environment, especially water temperatures, on the behavior and biology of WRL has been extensively studied by several authors. In general, warmer water temperatures can expedite many life history processes, from the timing of molting, migration, and reproduction to the age at which sexual maturity is attained and the likelihood of a lobster entering a pot. Habitat loss and alteration are particularly concerning as the effects of change on WRL survival and recruitment could be linear, non-linear or may be linked to undetermined thresholds of loss.

Remote sensing offers the potential to track seascape and habitat changes at bioregional spatial scales and has previously been used for fisheries applications. However, long-term tracking of habitats with remote sensing is challenging, particularly in marine environments. Even with the increased accessibility of aerial imagery and in-situ benthic habitat data worldwide, there remains limited long-term information on habitat and climate change that allows for causal inference on the population dynamics of fisheries species that may rely on shallow-water habitats for recruitment. Monitoring changes in WRL recruitment as a response to changes in the extent of recruitment habitat (SAV) or MHWs could be achieved through the use of remote sensing platforms such as Landsat or Sentinel-2.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Mastrantonis, S. et al. 2025. Disconnect between settlement and fishery recruitment driven by decadal changes in nearshore habitats. Science of The Total Environment Volume 968, 10 March 2025, 178785) – reports on a study that presented multidecadal extents of submerged vegetation and settlement indices for five coastal locations throughout the range of Western rock lobster and explored how these vegetation trends relate to an index of recruitment.

Study setup

We investigated changes in the extent and landscape characteristics of SAV since 1987 for five coastal locations on the mid-west Australian coast that have been concurrently monitored for puerulus settlement and standardized undersize catch rate of WRL as a measure of recruitment.

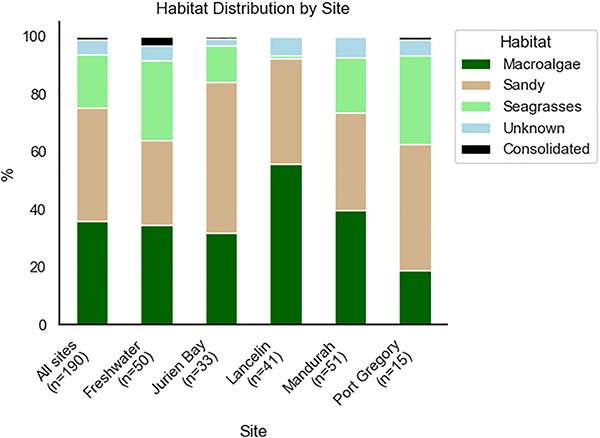

Five study locations were selected along the west coast of Australia, spanning the major fished area for Western rock lobster, and where puerulus settlement is monitored using artificial seaweed stations by the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. The study locations used in this research covered 600 km spanning, have a depth range of zero to 30 meters below sea level and predominantly feature the brown macroalgae Ecklonia radiata and unconsolidated (sandy), consolidated (rocky) substrate and seagrasses present at lower abundance.

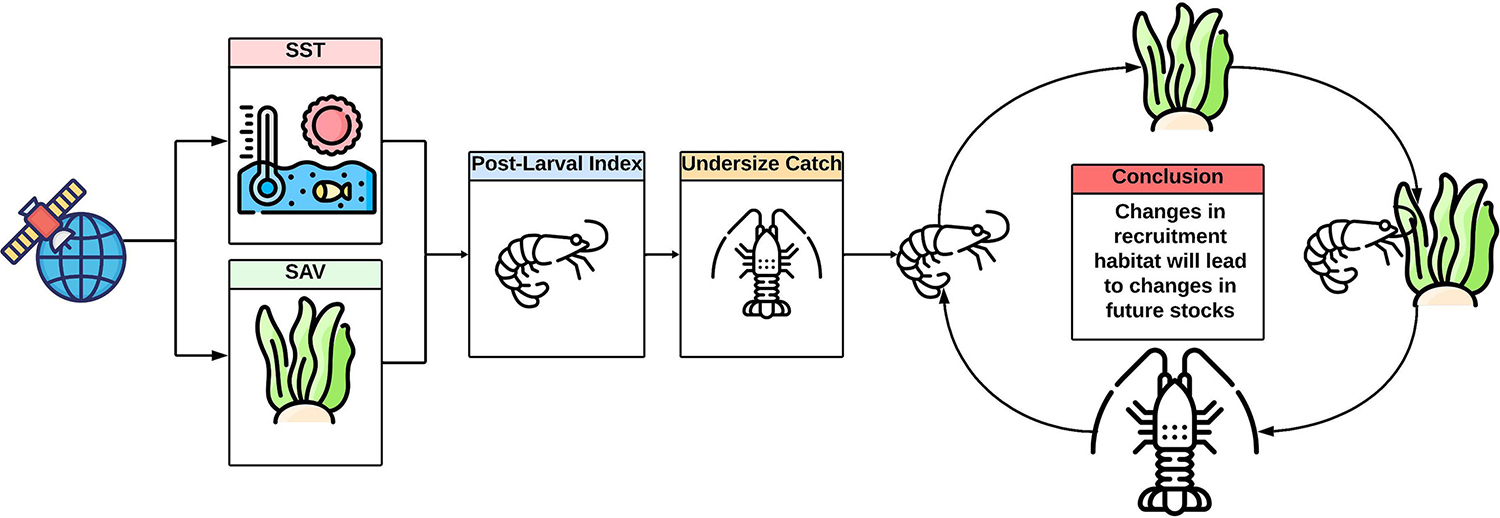

We modeled the relationship between undersize catch rates and the covariates of vegetation change, settlement indices, and long-term climate trends such as Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) and Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomalies. We hypothesized that undersize catch rates for any given year at the five monitored locations would be significantly affected by changes in puerulus settlement rates and recruitment habitat extent, represented by SAV, or extreme temperatures in previous years. And we suggest that nearshore invertebrate fisheries worldwide that model catch from settlement would benefit from integrating long-term habitat metrics to improve predictions and management.

For detailed information on the experimental design; location sampling; remote sensing imagery, climate and SAV classification; and data analyses, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

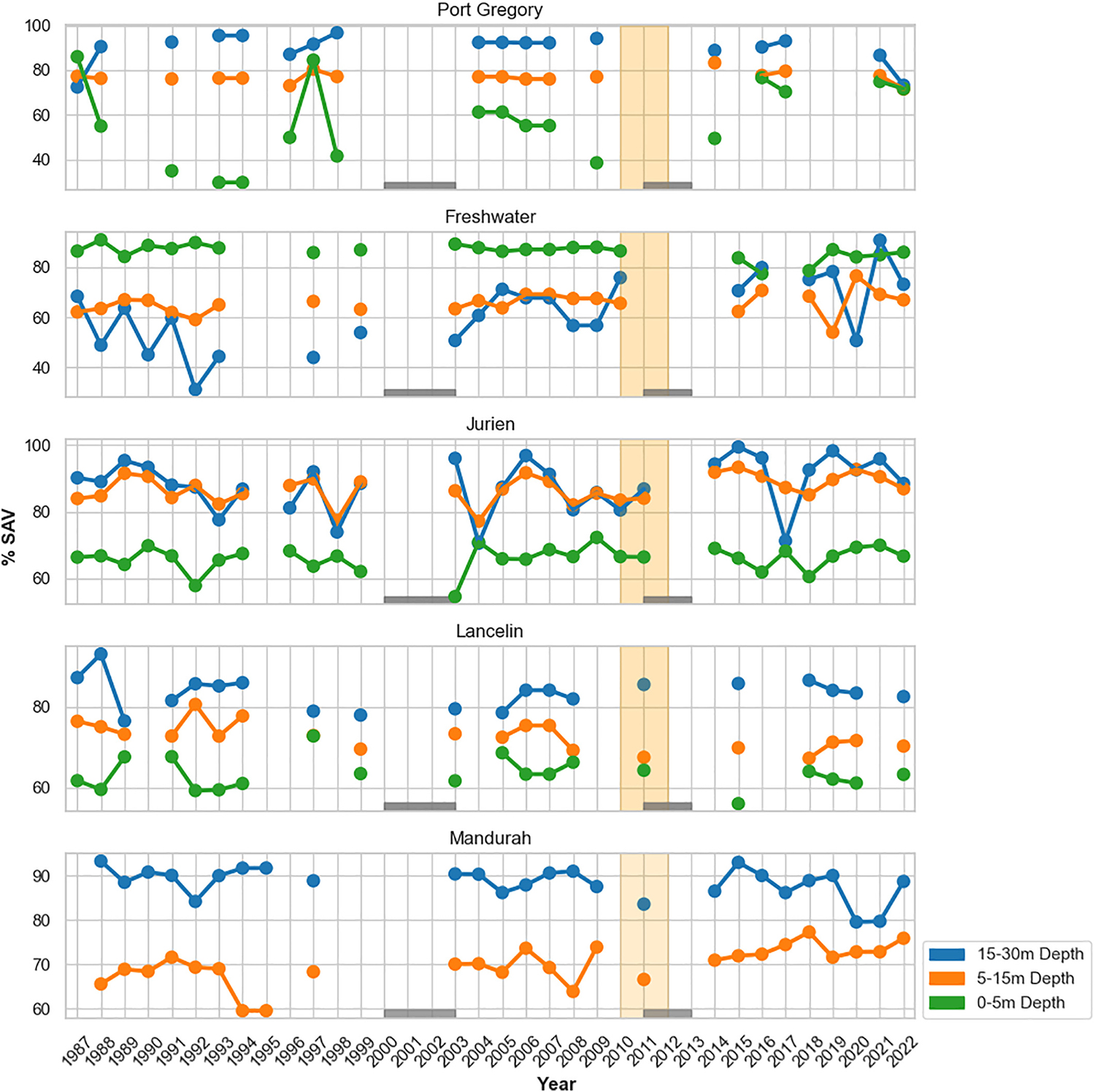

At representative locations, we have found a disconnect between settlement and fishery recruitment driven by decadal changes in nearshore habitats. We suggest that remote sensing of change in the extent of marine habitats at appropriate locations can complement long-term fishery data collection. Most of the observed changes in SAV extent have occurred in the shallows and around patches of SAV, and areas of contiguous SAV have remained relatively stable over this 30-year period. The application of nearshore remote sensing for habitat assessments should be considered by other managed fisheries across the world, particularly for invertebrate species whose recruits likely depend on algal or seagrass habitats.

Our work demonstrates that monitoring SAV extent using the Landsat inventory is possible and valuable for integrating habitat data into fishery assessment. However, it is important to state that monitoring extent and patch dynamics through Landsat, while representing the longest available time series, may not provide a realistic remote sensing measure of SAV condition or its true response to temperature anomalies. Changes in SAV conditions may occur at spatial scales and spectral resolutions that contemporary remote sensing platforms cannot detect. For example, the density or identity of SAV may change in response to temperature anomalies, but optical imagery is not sensitive enough to monitor the density or phenological traits of SAV. There is evidence that the MHW impacted SAV extent, but the lack of historical remotely sensed imagery obscures this relationship.

Tracking the coastal image quality through the Landsat inventory suggests that much of the intra-annual change in SAV extent occurs after periods of high turbidity observed in the satellite imagery. Much of the turbidity and sediment transport for the Midwest coast occurs during the winter months, and locations generally show increasing extents of sand following sediment transport, which gradually returns to SAV during the summer months. This intra-annual change is the primary reason we restricted image classification to the summer months, as the true trends in SAV extent for the study period may have been confounded by sediment transport during the winter. For the same reason, we avoided using composite images in this study, as image composition, though common and useful for correcting cloudy images, may mask any true SAV change at our locations.

Care needs to be taken when attempting to monitor SAV across time, as changes in SAV extent strongly depend on when and where you look. This has broader implications for any application of environmental ocean accounts to the WCRLMF, where the economic value of seagrass and macroalgae habitats may be linked to fishery output. Considering the life cycle of the WRL and the observed correlation between undersized catch and habitat in this study, estimating the true economic value of these habitats for the WCRLMF should integrate these contributions into the overall productivity of the fishery.

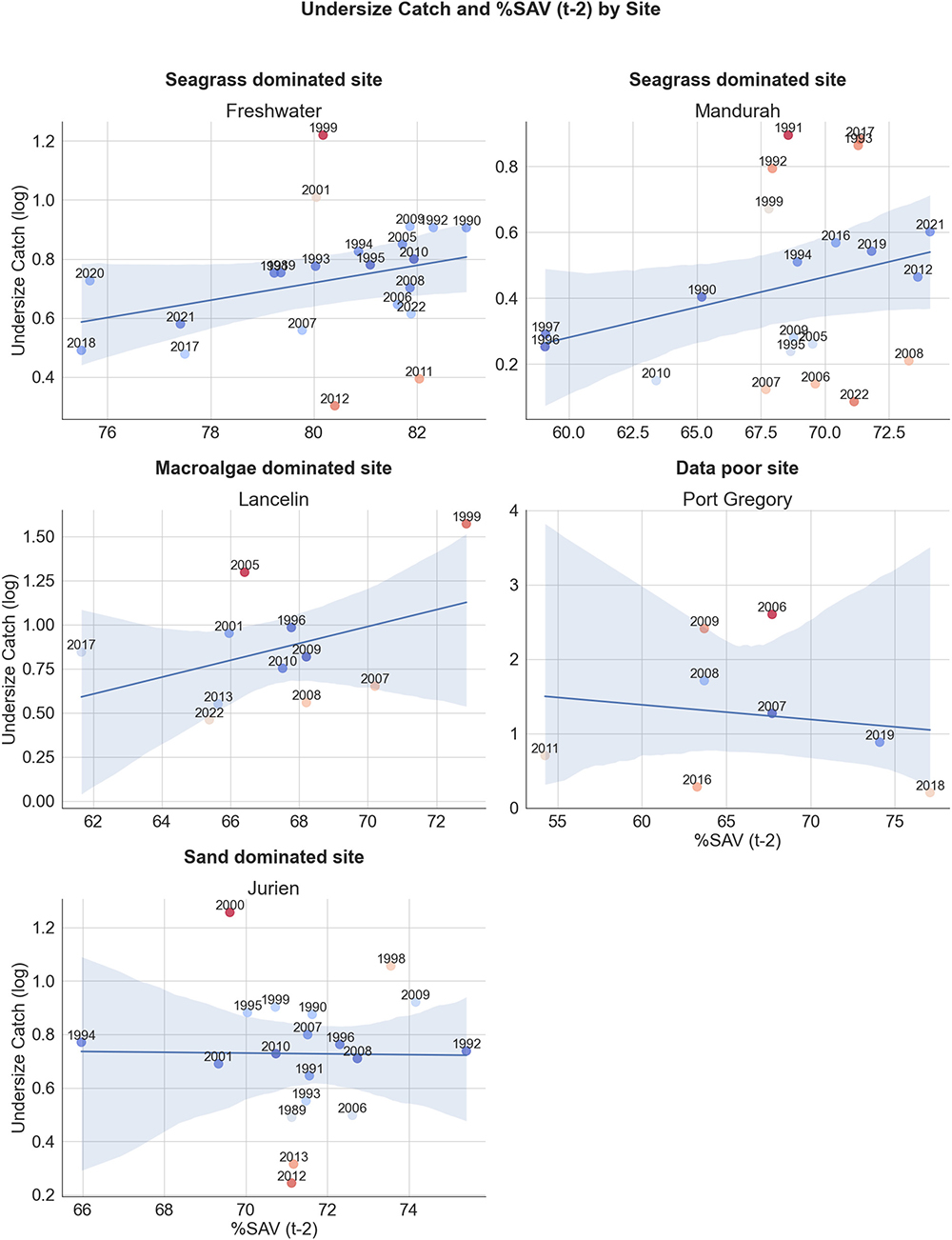

Despite the limitations in remotely sensed and undersize catch data, Freshwater, Mandurah and Lancelin showed a significant positive relationship between undersize catch and previous years of SAV. In contrast, Jurien, the most sand-dominated location, and Port Gregory, the location that lacked usable satellite and benthic imagery and catch data, showed no relationship between undersize catch and SAV.

Freshwater, in the center of the fishery, was an ideal location for this work as Landsat imagery was generally of good quality, and the undersize catch data was available for the study period. Freshwater was the location with the highest proportion of seagrass, followed by Mandurah, and the significant relationship between habitat and undersize catch rate in subsequent years for these two locations suggests that WRL population dynamics are closely tied to their recruitment habitats here. Thus, changes to this habitat, regardless of magnitude, could have cascading effects on the future recruitment of WRL into the WCRLMF. Indeed, including SAV extents into predictive models with the PI improves model predictions at locations such as Freshwater and Mandurah, and for the global model, implies that monitoring habitat change over time is useful for future fishery management.

Monitoring using remote sensing is frequently limited by spatial and spectral resolutions of available data, and spatial scale may well be a limiting factor in the work presented here. Though our chosen locations cover a significant area (~410 square kilometers) of coastline, this only represents a subset of likely available WRL recruitment habitats along the West Australian coast. Whole-coast monitoring of SAV may be necessary to determine the effects of habitat on WRL populations and the fishery as a whole. Careful choice of monitoring locations at fine spatial scales may provide better inference as to the true effects of climate. Future work may be able to identify regions of thermal refugia or regions experiencing extreme temperature fluctuations where loss or gain of SAV may be directly related to temperature anomalies.

While not incorporated into this study, oceanographic regime-driven settlement likely strongly influences the regional population dynamics of the WRL. Future work should integrate dispersal, sources and source-sink dynamics, long-term oceanographic models, habitat, and ocean productivity into fisheries models to better determine the WRL’s interactions with climate and habitat changes.

Perspectives

Our work demonstrates that tracking submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) extent revealed significant effects of habitat on Western rock lobster (WRL) recruitment for several locations on the mid-western coast of Australia. For locations with consistent temporal data and high seagrass composition, such as Freshwater and Mandurah, we found a significantly positive effect of future WRL recruitment to the extent of recruitment habitat (SAV). This represents an important finding for the management of WCRLMF and potentially other managed fisheries around the world, where the historical link of recruitment habitat to catch rates has yet to be quantified.

Potentially, critical recruitment habitats can now be monitored at scale using remote sensing, and we have demonstrated this process with the Landsat inventory, an instrument that is less than ideal for monitoring coastal habitats. Current instruments, such as Sentinel-2, and future instruments will provide finer-resolution imagery of coastal habitats that managers and scientists can use to monitor change at better spatiotemporal scales. We suggest that monitoring changes in the extent of marine habitats at appropriate locations can complement long-term fishery data collection and management in Australia and globally.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Stanley Mastrantonis

Corresponding author

School of Agriculture and Environment, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia[117,97,46,117,100,101,46,97,119,117,64,115,105,110,111,116,110,97,114,116,115,97,109,46,121,101,108,110,97,116,115]

-

Simon de Lestang

Western Australian Fisheries and Marine Research Laboratories, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, North Beach, WA, Australia

-

Tim Langlois

UWA Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

-

Ben Radford

School of Agriculture and Environment, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

-

Claude Spence

UWA Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

-

John Fitzhardinge

Dongara Marine, 169 Connell Road, West End, WA, Australia

-

Sharyn M. Hickey

School of Agriculture and Environment, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Lean and green, what’s not to love about seaweed?

Grown for hundreds of years, seaweed (sugar kelp, specifically) is the fruit of a nascent U.S. aquaculture industry supplying chefs, home cooks and inspiring fresh and frozen food products.

Fisheries

Fisheries in Focus: How the mystery of the great eastern Bering Sea snow crab die-off was solved

A research team has uncovered the reason why billions of snow crabs died in the eastern Bering Sea in 2021, closing the fishery for the first time.

Fisheries

Norwegian fishing vessel can ‘hand-pick’ Iceland scallops, a potential boon for bottom fishing

The Arctic Pearl scallop-fishing vessel is equipped with new technology that is sensitive to the ocean-bottom ecosystem of the Barents Sea.

Intelligence

Queen conchs conservation through aquaculture, education

While queen conchs have supported ocean fisheries for centuries, declining populations and catches have prompted management measures and aquaculture development.

![Ad for [f3]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/F3_web2026_1050x125.jpg)