Results show importance of adequately assessing benthic invertebrates’ vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, and effective oceanographic monitoring networks

Projected ocean acidification and deoxygenation in the California Current System (CCS) could harm ecologically and economically important species of decapods and echinoderms at every life stage. Predicting organisms’ vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation is incomplete without understanding their exposure to extreme conditions. Vulnerability is defined here as “the degree to which a system is susceptible to and is unable to cope with adverse effects.”

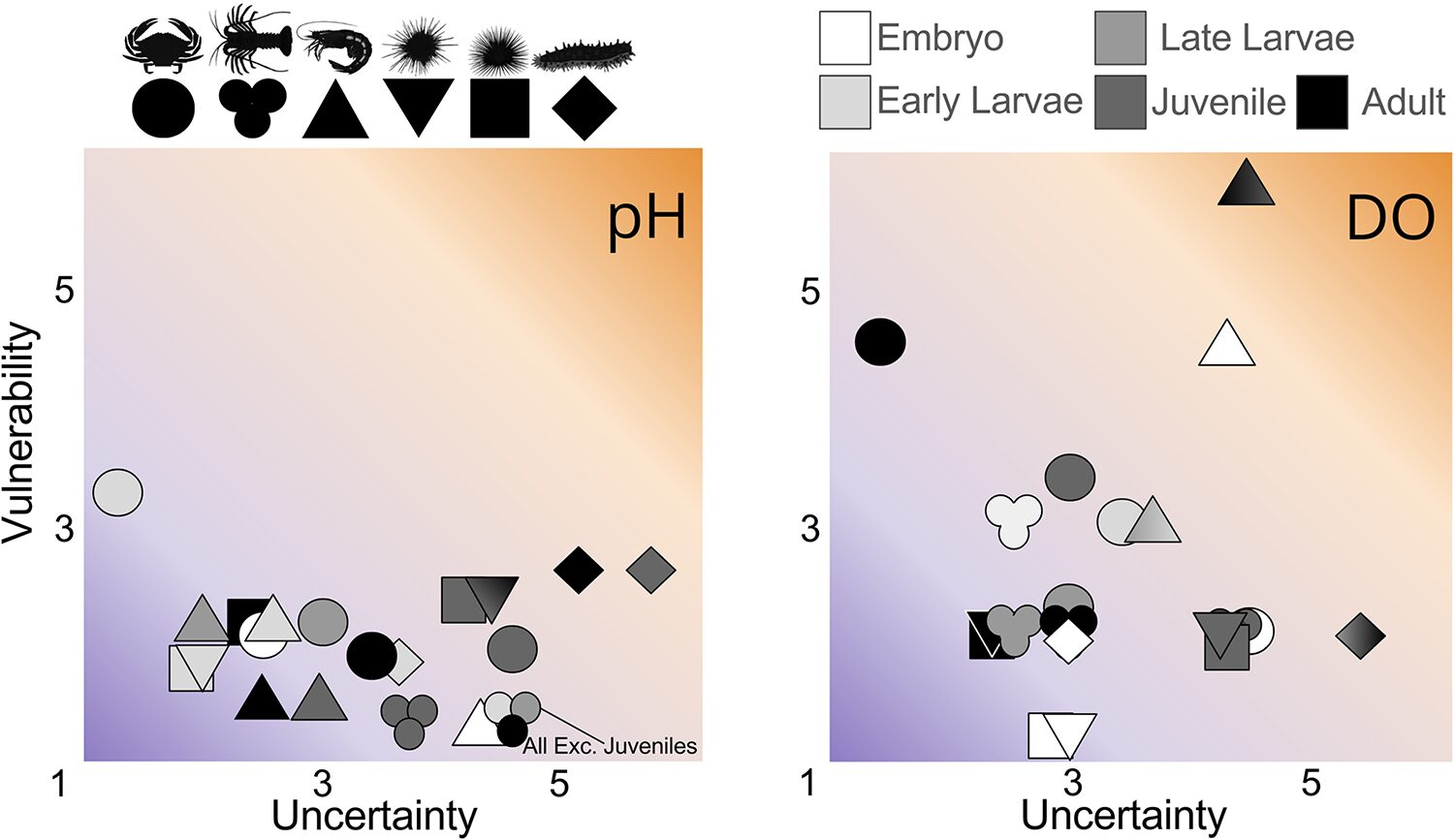

Direct oceanographic observations accurately estimate nearshore exposure and vulnerability, and are favored by resource managers over model outputs. Year-round fixed-location observations provide high temporal resolution at the expense of spatial coverage, while oceanographic surveys are spatially extensive but temporally limited. Individually, monitoring programs are insufficient for constraining exposure and vulnerability as they do not cover the full range of conditions experienced by organisms through space and time. To inform effective coastal policy, we need to understand species vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, and our degree of certainty in that vulnerability.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Zulian, M. et al. 2025. Assessing benthic invertebrate vulnerability to ocean acidification and de-oxygenation in California: The importance of effective oceanographic monitoring networks. PLoS ONE 20(2): e0317906) – presents the results of a study that assessed climate vulnerability and the uncertainty introduced by monitoring data gaps, using a case study of ocean acidification and deoxygenation in coastal California.

Study setup

The study used 5 million publicly available oceanographic observations and existing studies on species responses to low pH, low oxygen conditions to calculate vulnerability for six ecologically and economically valuable benthic invertebrate species. It also evaluated the efficacy of current monitoring programs by examining how data gaps heighten associated uncertainty.

Six invertebrate species were selected: red sea urchin (Mesocentrotus franciscanus), purple sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpurpatus), warty sea cucumber (Apostichopus parvimensis), pink shrimp (Pandalus jordani), California spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus), and Dungeness crab (Metacarnicus magister). Beyond their ecological and economic importance, we chose a suite of species that represent various biogeographic ranges, larval seasonalities and durations, and juvenile and adult depth distributions.

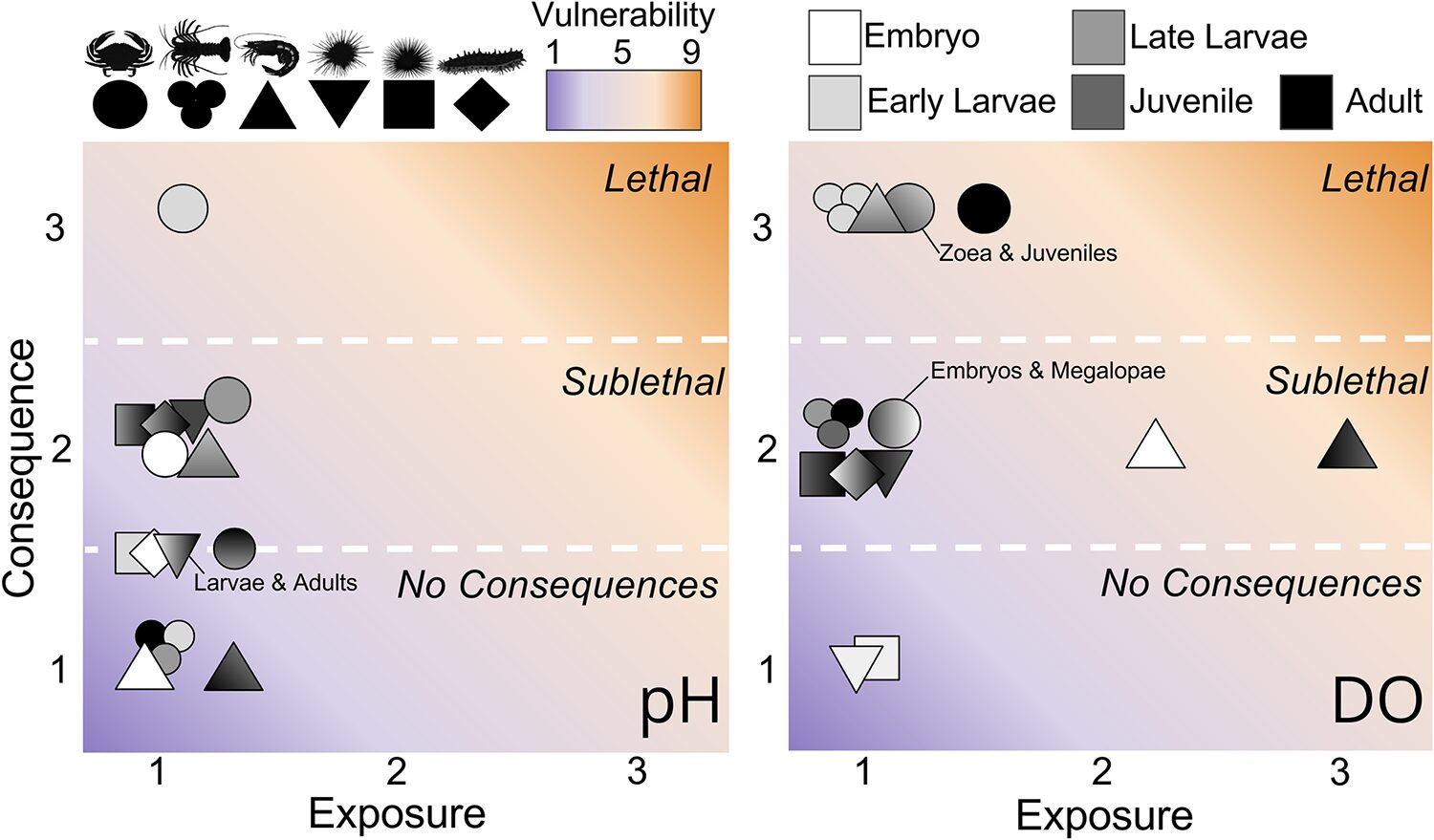

The study aimed to provide illustrative examples of how existing literature and oceanographic monitoring networks limit our vulnerability estimates in organisms of differing life histories and distributions. To assess these organisms’ vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, we investigated the overlap of stressful oxygen and pH conditions with their distribution throughout life history. We calculated life stage vulnerability as the product of exposure to low pH and oxygen and corresponding consequences. For detailed information on the study design, data sources and analyses, refer to the original publication.

Study: Fisheries managers should expect volatility due to marine heatwaves

Results and discussion

Benthic invertebrates’ vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation changes throughout life history, influenced by life stage sensitivities and varying exposure across dynamic habitat use. Our reported exposures are significantly lower than those previously reported for organisms in the northern CCS and those predicted for the future central CCS. With limited exposure rates across all organisms and life stages, physiological sensitivities and resultant consequences exert a stronger influence over species vulnerability.

Most life stages experience low pH conditions more frequently than low oxygen conditions. Exposure to either stressor is generally low, however, except for life stages occupying the greatest depths. The number of oceanographic observations available generally peaks in summer, when organisms generally experience the highest exposure to both stressors. This seasonal bias combines with significant spatial and benthic gaps in monitoring efforts, with important implications for resource management and constraints on vulnerability.

Results showed that deeper-dwelling organisms in the central CCS are exposed to stressful conditions more frequently than those in shallow waters, consistent with known declines in pH and DO with depth. Below the mixed layer – which is shallowest in summer (~15 m) and deepest in winter – atmospheric mixing cannot as readily replenish oxygen, nor ventilate waters enriched with dissolved inorganic carbon from upwelled waters or respiration.

Organisms that do not occupy surface waters (<30 m), such as adult Dungeness crab and pink shrimp juveniles and adults frequently experience low DO, low pH conditions within their common depth range. These life stages also frequently experience pH and oxygen conditions just above threshold values, suggesting their exposures will substantially increase with near-future declines of oxygen and pH. However, at least for pink shrimp, populations at the maximum extents of their depth ranges already frequently experience conditions that surpass biological thresholds, which could confer resilience as ocean acidification and deoxygenation progress.

Seasonal variation in exposure is most dramatic for organisms that do not occupy surface waters, and particularly for at depths where conditions hover around threshold values. Exposure to hypoxic and acidic conditions peaks in summer for all life stages. However, for shallow dwelling organisms and life stages (<80 m), particularly those occupying surface waters, seasonal fluctuations are minimal.

Though seasonal and annual scores were relatively similar for most organisms in this study, exposure calculations that equally weight data from throughout the year may underestimate the physiological consequences of chronic seasonal exposure, particularly if there is limited recovery time between subsequent events. Future vulnerability assessments for benthic invertebrates would benefit from examining seasonality, irrespective of perceptions regarding the degree of seasonality in the region.

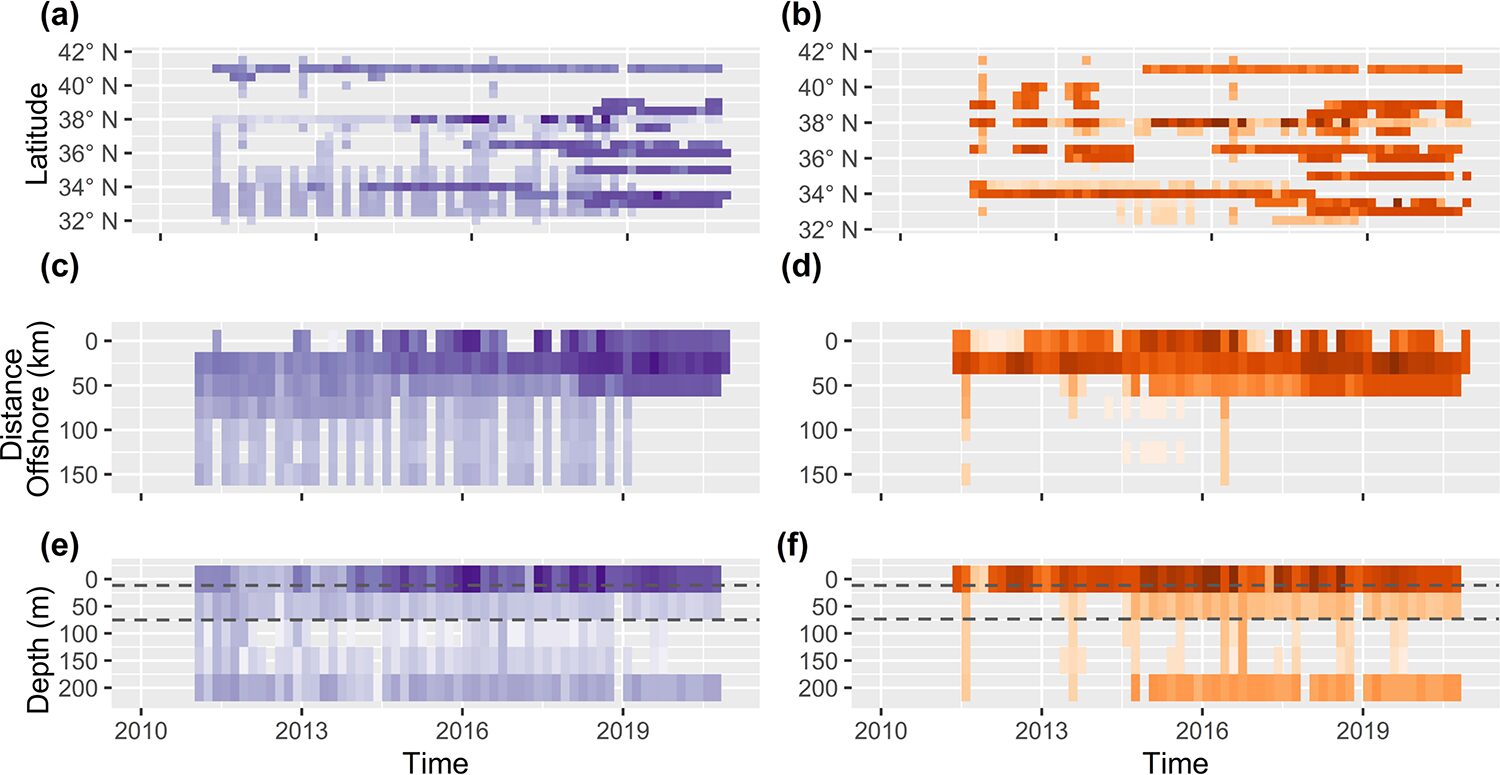

Though California is home to one of the most comprehensive oceanographic monitoring networks, latitudinal data gaps pose significant challenges in estimating species vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation. Latitudinal data gaps are the most common source of uncertainty in DO exposure calculations, and second greatest source of uncertainty in pH exposure calculations. Aside from 2016 when monitoring coverage peaked, there are consistently hundreds of kilometers of unsampled coastline (Fig 2a). Sporadic spatial coverage makes it challenging to accurately estimate species range of exposure to low pH, low DO conditions, which is highly variable across small spatial scales.

The number of oxygen (left) and pH observations (right) at < 250 m and < 100 km from shore along in the last decade. Data coverage is viewed across latitude (a, b) and distance offshore (c, d), and the number of near-bottom (<25 m from seafloor) oxygen (e) and pH (f) observations across depth. Dashed line denotes the minimum and maximum mixed layer depths. Adapted from the original.

Oceanographic sampling in California, especially ship-based sampling, is biased towards spring and summer, posing unique challenges for evaluating different life stages’ exposure to acidic, hypoxic conditions. Ship-based sampling is one of the few options for capturing conditions experienced by deeper dwelling life stages that do not occupy surface waters (0–25 m), and early life stages that travel far offshore. Though ship-based sampling efforts intentionally set out in spring and early summer to capture maximum exposure to stressful conditions, a bias towards spring and summer data could result in overestimates of annual exposure and vulnerability for life stages at depth, and offshore. Temporal sampling biases pose an ever-greater challenge for early life stages that are not present during peak sampling.

Species and life stages investigated herein significantly differ in their exposure to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, existing monitoring coverage across their distribution, overlap of fishing effort with the season of maximum stress, and the degree of environmental data considered in management decisions. For most species and life stages investigated herein (i.e., spiny lobster, sea cucumber, red, and purple urchin), current exposure and vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation are likely too minimal to warrant immediate management action, though the potential impacts of ocean acidification are making their way into some management plans.

For species with life stages that experience high, and strongly seasonal exposure to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, or severely lack data for such assessments, precautionary principles and proactive management strategies may be necessary to avoid over-extracting from vulnerable populations. Unfortunately, at present, ocean acidification and deoxygenation are not explicitly considered in harvest control rules, or essential fisheries information data collection, despite well-documented impacts on bottleneck life history stages and anticipated impacts on feeding, reproduction, growth, and thus age at maturity, and survival. Managers may want to consider ways to incorporate more environmental data, particularly considering that other dominant stressors (i.e., whale migration, domoic acid) are often related to the same processes that create low pH and low oxygen conditions.

To assess multiple stressors using oceanographic data, researchers must either limit analyses to locations where there is simultaneous monitoring of DO and pH, or use an exposure metric that eliminates the element of time, such as intensity, defined as the negative magnitude of the departure from the threshold. But limiting the analysis to co-measured data would greatly limit data availability to assess species and life stage exposure to stressors across the state of California over a period of 12 years, resulting in much higher uncertainties, and likely the exclusion of life stages who may have no contemporaneous pH and DO monitoring within their distributions. Even with improved oceanographic monitoring, there are insufficient studies examining the concurrent impact of low pH and low DO stress, to accurately assess their cumulative sensitivity and vulnerability.

With respect to consequences, the accuracy of our predicted responses is limited by the number of studies conducted on species and life stages of interest, and closely related species. Ideally, sensitivity studies across a range of plausible low pH or low DO conditions would be available for each species and life stage of interest, providing a continuum of null, sublethal, and lethal responses that could be used to accurately assess species vulnerability.

With the current literature available, it is not possible to incorporate evidence of local adaptation and the resilience it confers in a more robust way, within this, and other vulnerability frameworks. Future vulnerability assessments would greatly benefit from more studies that explore local adaptation to low pH and DO conditions, on a wider variety of species and life stages.

Perspectives

Though there are still significant unknowns in benthic invertebrates’ vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation, here we observe clear patterns in exposure and vulnerability. Life stage and species distribution are important factors to species exposure. However, with such low overall exposure, physiological sensitivity ultimately drives vulnerability. Our results highlight how laboratory experiments examining the impacts of low DO on multiple life stages, better-constrained species distributions, and targeted and sustained monitoring efforts could improve our understanding of vulnerability for many ecologically and economically valuable benthic invertebrates across the state.

One source of uncertainty not widely discussed in marine ecological vulnerability assessments is a lack of detailed information and formal consensus on species depth distributions. The amount of detailed information on life stage and species distributions strongly depends on their economic value and the type of fishing equipment used in their extraction. For example, Dungeness crab and pink shrimp fisheries that employ traps and nets have accurately constrained the common depth range of these species, compared to warty sea cucumber, whose distributions are quite elusive. Irrespective of using oceanographic data or models, more detailed information on species distributions is needed for accurate vulnerability calculations.

Adequately assessing benthic invertebrates’ exposure and vulnerability to ocean acidification and deoxygenation will require a concerted and critical funding and sampling effort. We encourage future monitoring efforts to prioritize fishing areas, depths, and open seasons while addressing latitudinal data gaps, and prioritizing benthic sampling at relevant depths.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Meghan Zulian

Corresponding author

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA[117,100,101,46,115,105,118,97,100,99,117,64,110,97,105,108,117,122,109]

-

Esther G. Kennedy

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Sara L. Hamilton

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Tessa M. Hill

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Genece V. Grisby

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Aurora M. Ricart

Institut de Ciències del Mar, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (ICM-CSIC), Barcelona, Spain

-

Eric Sanford

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Ana K. Spalding

School of Public Policy, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA

-

Manuel Delgado

Bodega Marine Laboratory, Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

-

Melissa Ward

Department of Geography, San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

AI-powered crab gender identification could improve fishery management and conservation

An AI-powered model developed by researchers "vastly outperformed" humans in correctly identifying the gender of horsehair crabs.

Fisheries

Rethinking ropes: Can ropeless fishing gear end whale entanglements?

Ropeless fishing gear can prevent whale entanglements and reduce the amount of discarded or lost fishing equipment but the cost is a limiting factor.

Intelligence

Pandemic persists and Pacific NW shellfish sector digs in

Eight months into the pandemic, the gloom and doom has lightened and there’s hope in the air for the Pacific Northwest shellfish sector.

Fisheries

Fisheries in Focus: How the mystery of the great eastern Bering Sea snow crab die-off was solved

A research team has uncovered the reason why billions of snow crabs died in the eastern Bering Sea in 2021, closing the fishery for the first time.

![Ad for [Aquademia]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/aquademia_web2025_1050x125.gif)