Study used fishery-dependent data and stakeholder input to understand fleet dynamics of all gillnet and trap/pot fisheries in U.S. Atlantic Ocean waters

Trap/pot and gillnet fisheries span the U.S. Atlantic continental shelf waters from Maine to Florida within the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Fleet dynamics and gear configurations vary regionally and are largely defined by targeted species. The American lobster (Homarus americanus) and Jonah crab (Cancer borealis) dominate New England waters within the trap/pot fishery, while various species of crab, fish, and gastropods are targeted coastwide. New England gillnet fisheries target groundfish like Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), pollock (Pollachius virens), flounder species, monkfish (Lophius americanus) and elasmobranchs (skates and dogfish).

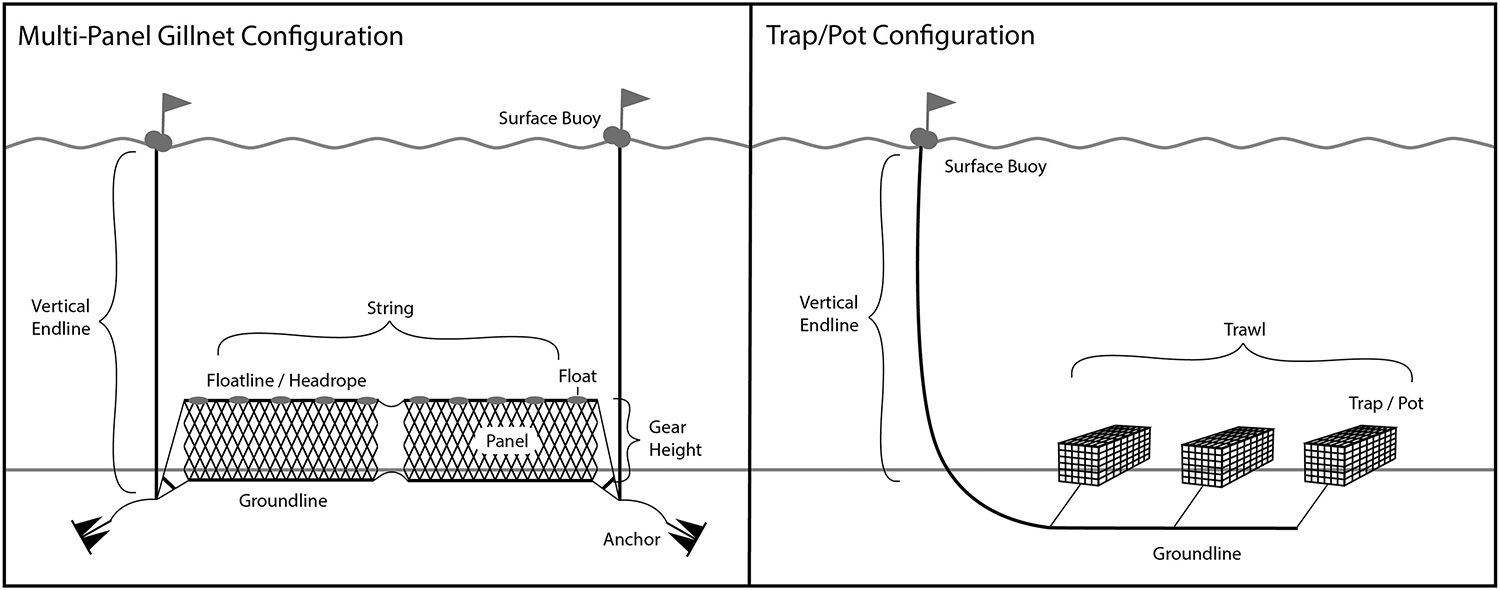

Configurations of traps and pots are generally characterized by the number of traps per trawl (the general term for multiple traps/pots on a line) and endlines. Endlines are used to connect the terminal end of a trawl to surface buoys that mark the location. Gillnets are similarly configured with endlines and one or more net panels per string. Gillnets have more complicated and variable gear configurations, often based on target species and region. Efforts to describe and quantify fixed-gear fishery density and dynamics in the U.S. Atlantic must account for these species- and gear-specific characteristics as they affect the ability of each fishery to modify or relocate gear.

Quantifying fixed-gear fisheries in space and time is an aspect of marine spatial planning (MSP) that has been absent until recently and still hindered by a lack of data precision in reporting and monitoring. Characterizing fishing effort across large spatial extents is challenging given the variability in targeted species, gear type, and configuration as well as regulatory requirements around management, monitoring, and reporting. However, even where data are limited there have been successful applications of quantifying gear to more accurately estimate impacts of fishing effort on coastal habitat and bycatch of protected species.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Miller, A.S. et al. 2025. Gearing up: Methods for quantifying gear density for fixed-gear commercial fisheries in the U.S. Atlantic. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Volume 82, 7 October 2025, Pages 1-15) – reports on a study that used fishery-dependent data and input from stakeholders to discern fleet dynamics of all gillnet and trap/pot fisheries in U.S. waters of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean.

Study setup

As space conflicts arise from competing ocean uses, there is an increased need to understand and categorize fixed-gear fisheries to incorporate into marine spatial planning (MSP) efforts. We used fishery-dependent data and input from stakeholders to discern fleet dynamics of all gillnet and trap/pot fisheries in U.S. waters of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean.

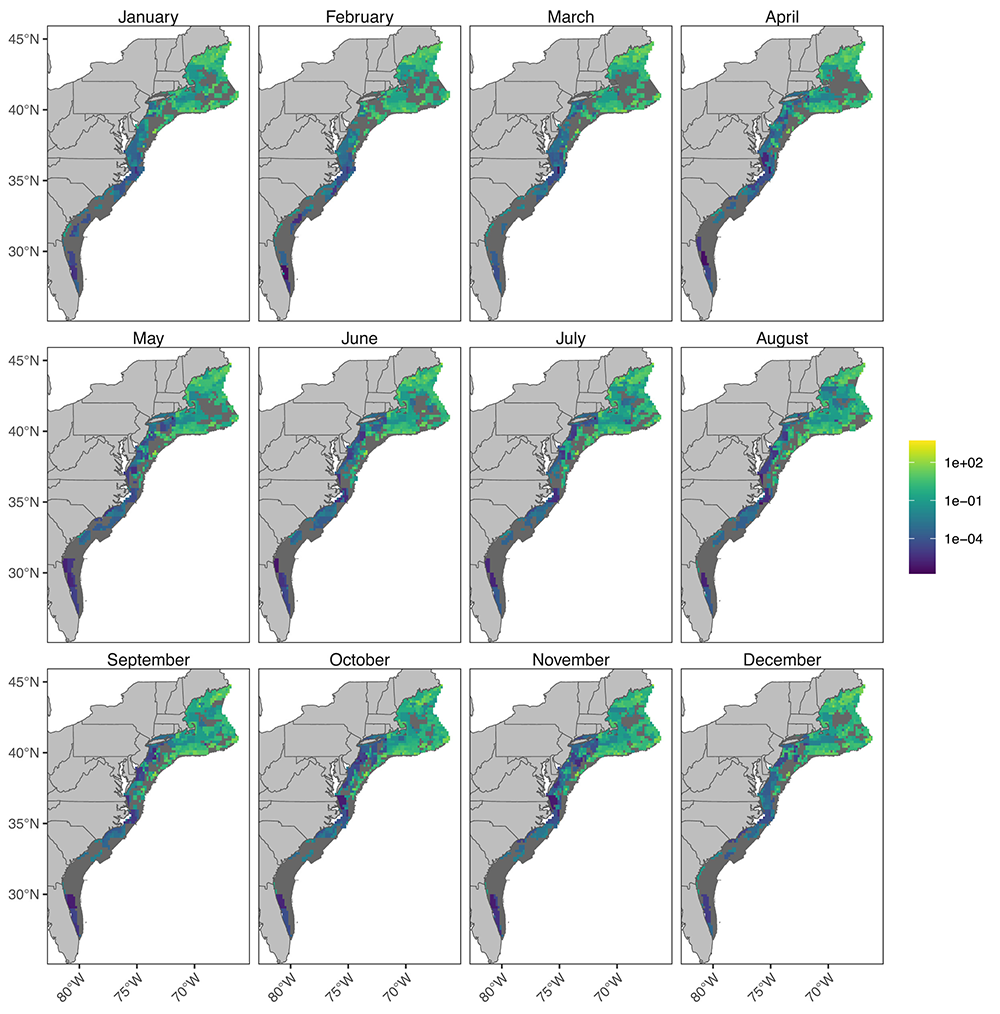

A Fixed-Gear Fishery Layer (FGFL) – which described monthly variability in fixed-gear density throughout the U.S. Northwest Atlantic – was developed combining fishery subgroups that were categorized around gear type, gear configuration, and species landed. Fishing effort from each subgroup was spatially allocated onto a 1 square nautical mile, nm2 (1.9 km2) grid using methods that relied on the level of detail available from trip reporting and monitoring, each with differing degrees of spatial resolution. This stepwise process allowed trips reported with minimal spatial detail to be included while not compromising trips where greater spatial precision existed.

To combine these data sources together into a useful product for MSP, we apply a systematic process for categorizing and quantifying fixed-gear fisheries. As a first step, fishery subgroups were established based on fishery type and management. Trip reported effort was then allocated over space and time using methods that prioritized spatial precision. This culminated in the development of a Fixed-Gear Fishery Layer (FGFL) that combines these fishery subgroups, providing estimates of gear and endline density from all trap/pot and gillnet fisheries within U.S. Atlantic waters.

For detailed information on the study design; data acquisition; construction of the FGFL; gear allocation methods, and other aspects, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

Accounting for both trap/pot and gillnet fisheries, the Fixed-Gear Fishery Layer (FGFL) described monthly variability in fixed-gear density throughout the U.S. Northwest Atlantic (Fig. 2). Gear density coastwide was lowest from January to March and steadily increased to a peak between July and October. Year-round, the greatest gear density was dispersed in northern waters from Maine to North Carolina. Gillnet fisheries had hot spots in southern New England and Gulf of Maine waters, but the greatest amount of effort existed from trap/pot fisheries in waters off the coast of Maine.

Broken down by gear type, trap/pot fisheries made up 99.6 percent of the GearDensity – GearDensitym,c – a measure of the monthly fishing intensity summed across all fisheries – across all months coastwide. Over 50 percent of total GearDensity coastwide was attributed to state-permitted American lobster and Jonah crab fisheries, with the federally-permitted component making up another 48 percent. The remaining 2 percent of coastwide GearDensity was represented by over 50 state and federal gillnet and trap/pot fishery subgroups.

This work represents the first and only comprehensive quantitative estimate of fixed-gear fishing effort in U.S. Atlantic waters. While originally developed as an input for a DST to mitigate risk of entanglement to right whales, it has since expanded to other MSP uses including applications to offshore wind energy development, other protected species, and aquaculture planning. Properly categorizing, describing, and quantifying fixed-gear fisheries supplies resource managers and stakeholders with a baseline as they are faced with managing ocean-use conflicts. Developing methods for handling disparate data provided a solution for combining all fixed-gear fisheries into a single FGFL product without compromising precision where data collection was rich.

Although this work was specific to fixed-gear fisheries in the U.S. Atlantic, the methods for building fishery subgroups may be applicable to other fisheries outside of this study area. Focusing systematically on gear type, gear configuration, species life history, and management units provided a logical method for grouping data into fishery subgroups. Determining species groupings required a balance between specificity of closely linked species and maintaining subgroups with enough data.

This part of the process was important in order to reduce bias that can occur when not all fisheries are included. Adding stakeholder engagement helped inform and refine these groups. Using monthly averages across different subsets of years for fishery subgroups allowed us to capture the most realistic trends in fishing behavior. Building the final FGFL from species- and gear-driven subgroups on a monthly scale also allows for subsetting by these descriptors, providing a more functional product for MSP, and one that can be easily applied to management.

Rethinking ropes: Can ropeless fishing gear end whale entanglements?

Making use of supplementary data sources including observer reports, interviews with stakeholders, and other activities was a step toward addressing calls for a “deep knowledge” approach when incorporating fishing into MSP. Observer data were useful for verifying reported gear metrics and filling data gaps, particularly in New England and the Mid-Atlantic where observer coverage was more widespread. Open and frequent communication with members of industry and management bodies across all states was critical to many steps including building fishery subgroups, verifying spatial distributions, and classifying gear.

Examining fisheries for different uses of the FGFL shows its role in marine spatial planning (MSP). By overlaying spatial data from other ocean uses, it is possible to measure the potential impact on fishing gear from developments like offshore wind energy. This process helps to consider fixed-gear fisheries, but it does not mean all will be displaced. However, the success of any new development will rely on identifying the existing stakeholders that may be affected, and opening communication about safety and cooperation to avoid conflicts that may arise.

Perspectives

Fisheries are constantly changing and the structure and methodology used in this approach are suitable for adapting to new and dynamic data across various spatial scales. As data collection and reporting improves and technology provides more accurate and precise fisheries data through programs like vessel tracking and monitoring, updates can be made that will increase the use of methods that are more spatially explicit.

Changes in species distributions and abundances as well as fleet dynamics and related economics will require revisiting trip reports and updating the FGFL over time. These updates will coincide with prospective and ongoing marine use developments, serving as both a vital layer for considering fisheries impacts on the U.S. Atlantic coast and a method for developing similar layers for other areas of the world to better incorporate fisheries into MSP.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Alicia S. Miller

Corresponding author

Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Woods Hole Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA[118,111,103,46,97,97,111,110,64,114,101,108,108,105,77,46,97,105,99,105,108,65]

-

Laura K. Solinger

Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Woods Hole Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

-

Burton Shank

Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Woods Hole Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

-

Alessandra Huamani

Integrated Statistics, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

-

Michael J. Asaro

Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Woods Hole Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

-

Douglas Sigourney

Integrated Statistics, Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

Related Posts

Fisheries

Can using biodegradable fishing gear help reduce the cost of ghost fishing?

Biodegradable fishing gear must improve to help address the environmental and economic impacts of ghost fishing, a new study concludes.

Fisheries

NOAA seeks to improve North Atlantic right whale risk assessments

NOAA Fisheries says a recent peer review of its North Atlantic right whale risk assessment tool will lead to management improvements.

Fisheries

Balancing protection and production: Diving into the North Atlantic right whale conflict with lobster and crab fishing

A closer look at the conflict between North American fixed-gear fisheries and North Atlantic right whale protection measures.

Fisheries

MSC suspends certification for Maine lobster fishery, enraging state’s political leaders

Maine’s governor and Congressional delegation say activists with an "axe to grind" led to the Marine Stewardship Council's decision to suspend Maine lobster’s certification.