Shellfish experts like author Rowan Jacobsen and Chris Quartuccio discuss marketing strategies for a growing corps of oyster farmers

Glidden Points and Great Whites. Cotuits and Cuttyhunks. Hama Hamas and Hog Islands. Moonstones and Murder Points.

The oyster – only a handful of the sedentary shellfish species are cultured in North America (five if you include the polarizing European Flats). Yet there are seemingly countless varietals, each distinguished by a mosaic of unique flavors – lovingly dubbed merroir – bestowed upon them by the nutrients in the soils and waters of the bays, inlets or brackish river deltas they call home.

Many such mollusks are on the market, and those that connoisseurs crave typically sport a deep cup and tantalize the taste buds with a salty kick, metallic complexities and a mineral finish. The ones that are truly remembered, however, sport a catchy name like Pemaquids, Malpeques or Blue Pools.

To denominate an oyster is to give birth to a brand. So it better be good (and so should the oyster).

“Wherever I’ve worked with oyster farmers, branding is essential,” said Bill Walton, associate professor in Auburn University’s School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences. “Branding is a name. If you have a name for an oyster, it puts the farmer in a position where they have demand for that product in the market.”

Walton and other oyster farming experts shared their insights during an October webinar, Branding Opportunities for Oyster Farmers, produced by the National Aquaculture Association North Central Regional Aquaculture Center and United States Aquaculture Society. Walton was joined by enthusiastic oyster buyer and restaurant operator Bryan Rackley, who shared his thoughts on oyster quality, consistency and what it takes to stay on his menu.

Rackley is co-owner and shellfish manager of Kimball House in Decatur, Georgia, USA, which regularly features 18 oyster varieties each night. Which sounds like a lot of work, but Rackley relishes the task of keeping up with the bounty of brands looking to make a lasting impression on the raw bar scene.

“This is the job I created for myself, to curate this menu on a daily basis,” he said. “When something is new, and it sticks out, I’m excited to jump on it. But I’m more concerned with carrying the best as opposed to the most.”

The success and popularity of the oyster has led to numerous raw bar openings, some within already-established restaurants. Capitalizing on a food trend showing no signs of receding, oyster bar operators know that nobody comes in for one oyster, so displaying a healthy variety is crucial to satisfy the samplers.

Olympia Oyster Bar in Portland, Ore., opened only a year ago. Chef and owner Maylin Chavez says a place like hers is not a typical restaurant. “It’s a celebration,” she said. “Working around oysters is so fun, as a chef. And people are genuinely excited when they come in. You don’t get that with a lot of restaurants. It’s a culture of enjoyment and conviviality.”

A good variety of oysters, she added, is one hell of a conversation starter. She’s found that her customers are intrigued by the various, cool-sounding names, as they foster engagement with food and curiosity about where it came from and how it was produced. For instance, tumbling – a process in which oysters set in suspended mesh cages are gently tossed about with the tides, which limits outward growth of the shell edge and creates a deeper cup – is becoming as much of a sell factor as origin, Chavez said.

“I work closely with Hama Hama Co. [in Lilliwaup, Wash.]. They have a few oysters, like the Sea Cow, known for its stripes,” said Chavez. “Then they have the Blue Pools. They’re tide-tumbled, which makes a deep-cup oyster. They really brand them beautifully.”

The Essential Oyster

Oyster enthusiasts speak of these culinary treasures as dots on a map, for geography heavily influences the creatures’ characteristics. If not honoring the water in which they’re raised, oyster monikers are at turns whacky (Sea Cow, Beach Blonde), simple (Canada Cup, Olde Salt) or an homage to ancient cultures and exotic-sounding destinations (Kumamoto, Kusshi or Skigoku).

Few know more about oyster traditions and tastes than Rowan Jacobsen, the author of the 2007 classic “A Geography of Oysters,” a guide to oyster eating in North America that won the James Beard Award for Reference and Scholarship. His latest (and third) book on oysters, “The Essential Oyster,” was just published in October.

This fall, while touring the Southeast United States to support the book, Jacobsen told the Advocate during a roadside stop that geography is indeed the leading influence in oyster brands, but subtle signs show that’s changing.

“Capital Oyster is the one new big player in Puget Sound,” he said of the Olympia, Wash., company that put a little spin on its geography-based name. “They tumble their oysters, which is a huge trend on the West Coast. But [the method] sort of tumbles the geography out of the oysters. It influences the oyster so strongly, so the cultivation becomes more of a factor. Then there are the Sea Cows and Blue Pools. We’ll see more names that are not geography-based.”

More and more of our life is virtual, or processed. But oysters are so friggin’ real – a hunk of landscape on your plate; a real experience.

Jacobsen believes oysters are no passing fad, evidenced by raw bars popping up in places one might not expect. Charlotte, N.C., for instance, has a “booming” raw bar scene, he said.

“The enthusiasm you’ve seen on the East Coast and Pacific Northwest is now all over the country. Any oyster you can get to market size is spoken for,” he said. “The only thing could that stop this juggernaut is if they become uncool at some point. I’ve given up predicting what’s cool and what’s not!”

The love for oysters boil down to one thing, he added.

“[Oysters are] so real,” he said. “More and more of our life is virtual, or processed. But oysters are so friggin’ real – a hunk of landscape on your plate; a real experience.”

We took oyster branding to a new level. It was a marketing plan, not just a name slapped on it.

For buyers like Rackley in non-coastal towns (Decatur is just east of Atlanta), exotic oyster names get people talking and sometimes do all the selling. But he prefers the story each variety tells, and likes educating his guests. A fancy name is worth nothing, he adds, unless the quality is there.

“We want to be proud. We want to trust. There’s a lot of value in buying oysters that are not being resold,” said Rackley. “We buy direct from the farmer or from a co-op, so the oysters are arriving 24-48 hours out of water, Instead of a truck on a five, six-day journey.”

But a cool name has real power, said Jacobsen, not to mention the fact that oysters are the “poster child” for sustainable, authentic food.

“Murder Point is my favorite oyster name,” he admitted, referring to the oyster farmed in Alabama, sold with the tagline “oysters worth killing for.”

“And they’re beautiful,” Jacobsen said. “They very cleverly flipped the conventional wisdom of what you might use as a name. It sticks with you.”

Naked and unafraid

When it comes to naming an oyster for the sole purpose of selling a $#!&-ton of them, Chris Quartuccio has the last word. He’s the owner of Blue Island Oyster in West Sayville, N.Y., which he founded in 1995.

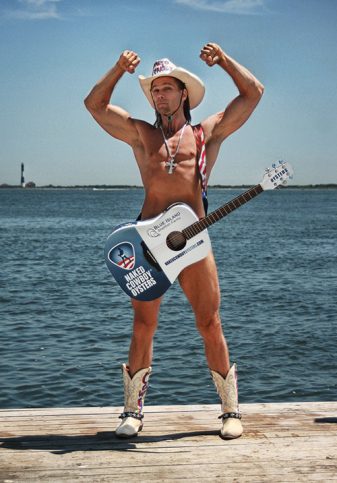

Quartuccio – who farms a variety of the Blue Point oyster that’s named Blue Island No. 9 – also sells wild, diver-harvested oysters. For years, his Wild Blue Islands sold fairly well, as most restaurants carried two to four varieties of oysters, tops. But things changed one day, when he was heading south on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan and saw the famous-in-New-York-only street guitarist and singer the Naked Cowboy performing on the sidewalk, in his customary tighty-whitey underpants, Stetson hat, cowboy boots and nothing else.

“He exemplifies New York. I thought, if oysters are an aphrodisiac, isn’t the Naked Cowboy? I mean, what’s rawer than him? He’s a wild guy, who’s bold and shocks people,” said Quartuccio, who soon approached the busker with a licensing agreement. He signed it several years ago and, according to Quartuccio, the partnership has resulted in oyster sales 10 times greater than under the previous name.

“We took oyster branding to a new level. It was a marketing plan, not just a name slapped on it,” said Quartuccio. “There were some early adopters, and other chefs didn’t want them, because of the name. It took a couple of years, but customers began asking for them, and now they’re sold all over the U.S.”

It may have been risky to hitch his wagon to a scantily clad and muscular musician, but Naked Cowboy is in the conversation as the most successful oyster name of all time.

“All the billboards in Times Square, nobody remembers,” said Quartuccio. “But they remember the Naked Cowboy. I told him five years ago that his name will not only be on restaurant menus all over the U.S., but this oyster brand will outlive you and me.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

James Wright

Editorial Manager

Global Aquaculture Alliance

Portsmouth, NH, USA[103,114,111,46,101,99,110,97,105,108,108,97,101,114,117,116,108,117,99,97,117,113,97,64,116,104,103,105,114,119,46,115,101,109,97,106]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Social oysters: Aquaculture inspiring communities

Two New England shellfish producers are furthering their innovative social license initiatives, both in their hometowns and in food-insecure regions overseas. Island Creek Oysters and Matunuck Oyster Farm have become admirable aquaculture ambassadors.

Intelligence

Dutch shellfish farmers bringing the sea onto land

Bivalve shellfish culture is a low-impact form of protein production, and in many cases is a net-positive for water quality. So why move it indoors? Smit & Smit in the Netherlands has a good argument for doing so.

Intelligence

Rubino, Knapp lay out ‘political economics’ of U.S. aquaculture

Michael Rubino and Gunnar Knapp list key reasons why U.S. marine aquaculture has been limited to a scale far below its vast potential.