The GFMI operationalizes gear-specific management by summarizing attributes linked to ecological sustainability, ecosystem effects, regulatory compliance, and socio-economic performance

The precautionary principle (emphasizes caution, pausing and review before leaping into new innovations that may prove disastrous) is a core principle of modern fisheries management including both single-species and ecosystem-based approaches. While this principle can be applied to manage single-species stocks, it is a foundational tenet of EBFM (ecosystem-based fisheries management; a holistic approach that recognizes the complex dynamics among target and non-target species and the broader social–ecological system), which applies it comprehensively to safeguard not only target populations but entire ecosystems. This principle entails proactively halting destructive fishing practices and ensuring the long-term health of marine resources. In the Republic of Korea, declines in the average trophic level of marine ecosystems coincide with overfishing, underscoring the central role of fisheries management in conserving marine resources.

Although EBFM is valued for indicator-based assessments of complex, fluctuating ecosystems, its uptake is constrained by limited data, unclear institutional responsibilities, and uneven adoption across jurisdictions. In particular, the Republic of Korea fisheries, characterized by a diverse mix of gear types and small-scale operations, have previously shown significant limitations in the application and expansion of fishery resource management systems such as the total allowable catch.

Specifically, with over 41 coastal and offshore fisheries operating under the Enforcement Decree of the Fisheries Act, the same species are caught with a variety of gear. Each gear has a different impact on the ecosystem depending on its fishing method and intensity. Consequently, existing species-centric models struggle to systematically compare and assess the impacts of these heterogeneous fisheries. Accordingly, this study takes fishing gear as the unit of analysis and proposes a Gear-based Fisheries Management Index (GFMI), derived from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) “ideal gear attributes.” The GFMI operationalizes gear-specific management by summarizing attributes linked to ecological sustainability, ecosystem effects, regulatory compliance, and socio-economic performance. It incorporates sectoral scale, production, and operating characteristics of Korean fisheries and provides a basis for comparative appraisal of each sector’s current management implications.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Kwon, I. et al. 2025. Development of a Gear-Based Fisheries Management Index Incorporating Operational Metrics and Ecosystem Impact Indicators in Korean Fisheries. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13(9), 1770) – discusses the results of a study developed a Gear-based Fisheries Management Index (GFMI) for 24 coastal and offshore fisheries in Korea.

Study setup

This study developed a Gear-based Fisheries Management Index (GFMI) for 24 coastal and offshore fisheries in Korea. The framework, based on the “ideal gear attributes” defined by ICES, is structured around three objectives: gear controllability, environmental sustainability, and operational functionality. Sub-indicators and weights were derived through expert consultation.

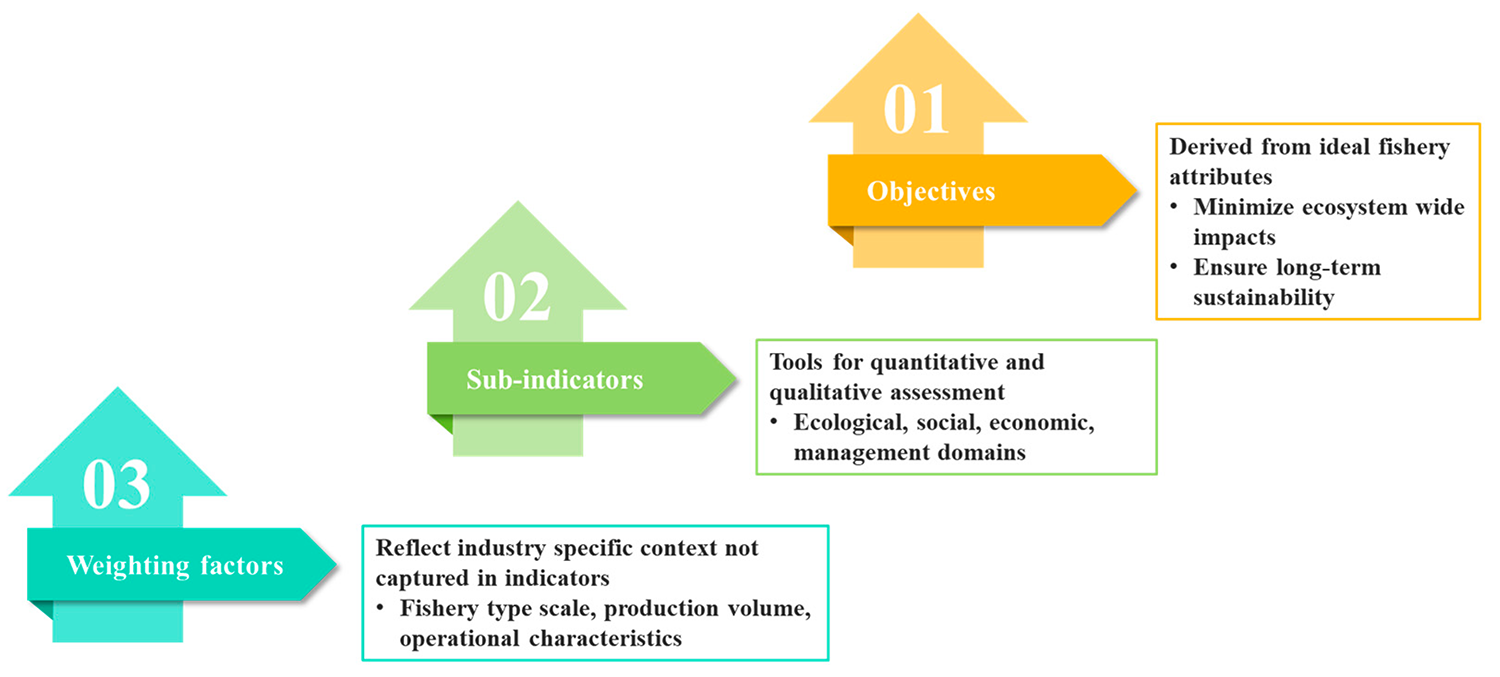

The Gear-based Fisheries Management Index (GFMI) consisted of three components objectives, sub-indicators, and weighting factors. In accordance with ICES, the “ideal gear attributes” were defined to systematize the appraisal of gear types and to identify responsible fishing practices. Three domains – catch controllability, environmental sustainability, and operational functionality –were specified, reflecting the aim of minimizing fishery-wide ecosystem impacts and securing long-term sustainability.

For detailed information on the experimental design, and data acquisition and analysis, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

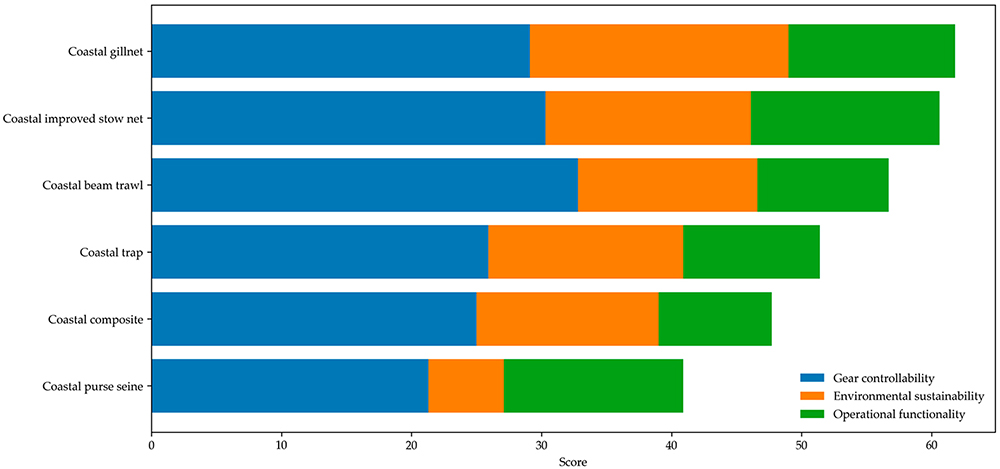

The GFMI developed in this study revealed gear-specific characteristics and vulnerabilities across Korea’s coastal and offshore fisheries. In the coastal fisheries, the coastal gillnet fishery and coastal improved stow net fishery showed relatively high overall GFMI scores, largely reflecting penalties on reproductive capacity, bycatch, and gear loss. National statistics likewise indicate substantial bycatch burdens: gillnets accounted for 71.2 percent of recorded bycatch and longline gears for 57.3 percent, the highest shares among coastal gears.

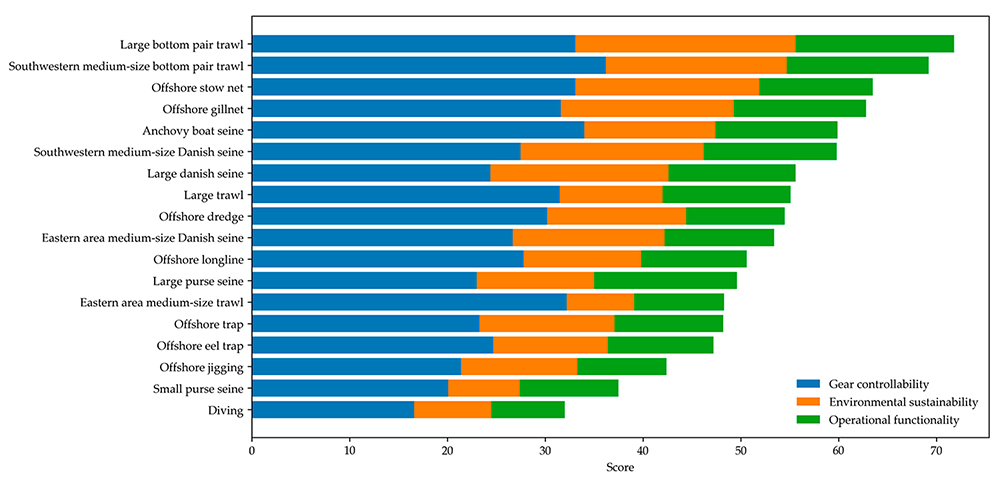

In offshore fisheries, large bottom pair trawls and Southwestern medium-size bottom pair trawl scored high. This indicates that trawl fishing operations scored high on sub-indicators such as habitat impact, reproductive capacity, and fishing mechanisms. In terms of operational functionality, coastal improved stow nets, coastal purse seines, and coastal large trawl fishing operations scored relatively high. This suggests vulnerabilities in gear cost and operational ease. Our findings provide a direct basis for developing goal-oriented, gear-specific policies to address industry vulnerabilities identified in this study.

For fisheries with high GFMI scores, such as coastal gillnet and coastal improved stow net fisheries, our results suggest the following policy considerations. To improve selectivity, given their poor performance in species selectivity and reproductive capacity, policies could encourage the use of larger-mesh gillnets or require escapement devices in stow nets to reduce the catch of non-target and juvenile species. To prevent gear loss, the high risk associated with gillnets suggests a need for policies that mandate biodegradable panels or require a comprehensive gear registration and tracking system. To promote gear substitution, the notable contrast between high-scoring gillnet and low-scoring coastal purse seine fisheries highlights a policy opportunity to incentivize a transition from less-selective, higher-impact gear types to more sustainable alternatives. The GFMI provides the quantitative evidence to justify such a shift. Lastly, to enhance crew safety, for fisheries with operational vulnerabilities like high gear costs or complexity, policies could focus on providing subsidies for safety equipment or mandating regular safety training to reduce operational risk.

Ultimately, the GFMI provides the evidence to support a nuanced, multi-faceted approach that addresses specific vulnerabilities, rather than a broad, single-instrument policy like a total ban on certain gear types. The GFMI developed in this study provides a quantitative, gear and fishery type level assessment. Whereas other frameworks are organized around species or ecosystems hindering like for like comparisons across gears and industries the GFMI treats 24 gear-based fishery types in Korea’s coastal and offshore fisheries as the units of analysis, enabling cross-gear comparisons and furnishing a practical basis for prioritizing management actions. By explicitly incorporating sectoral scale, production, and operating characteristics, the index captures the heterogeneity of Korea’s fisheries and embeds industrial context alongside ecological performance, thereby enhancing its policy relevance and practical applicability.

However, the GFMI has several limitations. First, it does not explicitly model species ecosystem interactions. Whereas EBFA and IFRAME incorporate predator prey dynamics, habitat change, and climate forcing, the GFMI is a gear level assessment that abstracts from these processes. Second, it is sensitive to data availability and imbalance. Some indicators can be quantified from national statistics, but others (e.g., accident rates, gear durability) rely on expert elicitation; uneven coverage across fishery types may affect comparability. Third, international comparability is limited: the index is tailored to Korea’s fleet structure and gear characteristics and is not intended as a universal metric. Fourth, temporal responsiveness is weak: because the index is computed from cross sectional data, it does not readily capture technological change, climate variability, or long run shifts in stock abundance.

In conclusion, the GFMI provides an intermediate alternative between qualitative, expert-only screening tools and data intensive ecosystem models. Its modest data requirements enable routine policy use, and its multidimensional structure integrates ecological, technical, and operational considerations at the gear level. In fisheries such as Korea’s marked by heterogeneous small and medium sized sectors the GFMI offers actionable, gear-specific diagnostics and supports the design of multidimensional management options.

Future work should incorporate explicit ecosystem dynamics (trophic and habitat linkages), strengthen data driven estimation, improve cross-national comparability through calibration, deploy time series applications for trend detection, and integrate socioeconomic dimensions. With these extensions, the GFMI could evolve into a practical, transferable fisheries management instrument with relevance beyond the national context.

Perspectives

This study presents a Gear-based Fisheries Management Index (GFMI) that evaluates 24 coastal and offshore fisheries in Korea using the ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) “ideal fishing gear attributes.” The index quantifies gear- and industry-specific management vulnerabilities, where higher scores indicate greater management risks and burdens. In coastal fisheries, gillnets (61.7) and improved stow nets (60.7) scored highest due to bycatch, reduced reproductive capacity, and gear loss, whereas coastal purse seines (40.9) scored lowest owing to advantages in species selectivity. In offshore fisheries, large bottom pair trawls (71.8) and Southwestern medium-size bottom pair trawl (69.3) scored highly, reflecting environmental impacts such as habitat disturbance. In terms of operational functionality, improved stow nets, large purse seines, and large trawls showed vulnerabilities related to costs and ease of operation.

Based on these results, the GFMI provides a practical basis for prioritizing multidimensional management actions, including improving selectivity, promoting gear substitution, preventing gear loss, and enhancing crew safety. Future work should broaden the index’s generality and policy utility by integrating trophic and habitat connectivity, strengthening data-driven estimation, establishing cross-national calibration, and expanding applications to time-series and socioeconomic indicators.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Inyeong Kwon

Department of Smart Fisheries Resource Management, Chonnam National University, Yeosu 59626, Republic of Korea

-

Gun-Ho Lee

Department of Maritime Police System, Gyeongsang National University, Tongyoung 53064, Republic of Korea

-

Young II Seo

Dokdo Fisheries Research Center, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Pohang 37709, Republic of Korea

-

Heejoong Kang

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan 46083, Republic of Korea

-

Jihoon Lee

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan 46083, Republic of Korea

-

Bo-Kyu Hwang

Corresponding author

Department of Public Service in Ocean & Fisheries, Kunsan National University, Gunsan 54150, Republic of Korea[114,107,46,99,97,46,110,97,115,110,117,107,64,103,110,97,119,104,107,98]

Related Posts

Fisheries

A qualitative systematic review of jellyfish mitigation for net-based fisheries

The co-existence of net-based fisheries and jellyfish requires close cooperation among fishers, managers and scientists.

Fisheries

Bycatch release tools help boost crew safety and sustainability in tuna fisheries

New onboard tech helps tuna fisheries release bycatch with minimal handling, improving crew safety and advancing sustainability goals.

Fisheries

‘A world down below’ – Deeper fishing insights lead to better tools for bycatch reduction

High-tech bycatch reduction devices – data analytics, cameras and sensors – are in play but SafetyNet Technologies says the secret is collaboration.

Fisheries

Fisheries in Focus: Busting misconceptions about bottom trawling and its environmental impacts

Fisheries researchers examine all environmental impacts of bottom-trawling and compare the fishing method to other forms of food production.

![Ad for [membership]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/membership_web2025_1050x125.gif)