Electric fence tech shows promise in stopping sea lice early, offering salmon farms a preventive, low-stress solution

Sea lice remain a perennial challenge for salmon farms, causing physical damage and stress, stunting growth, and in some cases, resulting in mortalities. Traditional treatment methods, such as mechanical and thermal delousing, add their own strain on fish health while driving up operational costs. And with sea lice becoming increasingly resistant to chemical treatments, finding effective, alternative solutions has become a top priority.

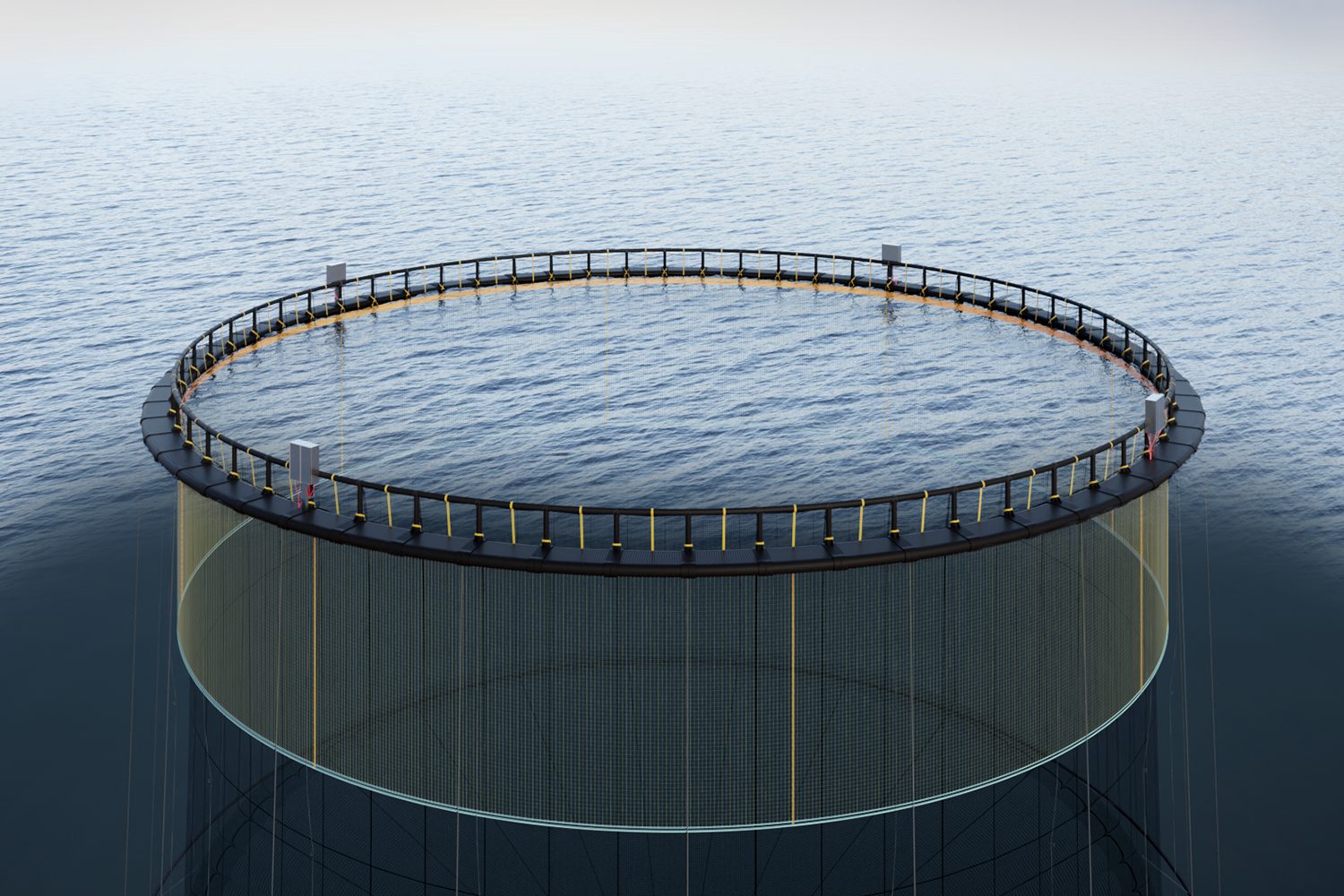

Now, researchers at the NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and Norwegian equipment supplier Harbor AS are trialing an unconventional method to deter sea lice from attaching to salmon: electric fences. The initiative is part of the BioSeaLice project, which is investigating whether the Harbor fence – an enclosing electromagnetic field around a salmon pen – can effectively reduce sea lice infestations.

“The idea is to create an electric barrier around the net pens,” Tarald Kleppa, head of research and development at Harbor AS, told the Advocate. “Sea lice generate a host of welfare, cost and mortality issues, putting the salmon sector under pressure with the need for costly treatments that also negatively impact fish welfare. We want to reduce this pressure before sea lice enter the net pens by immobilizing them using pulse trains, or electromagnetic fields.”

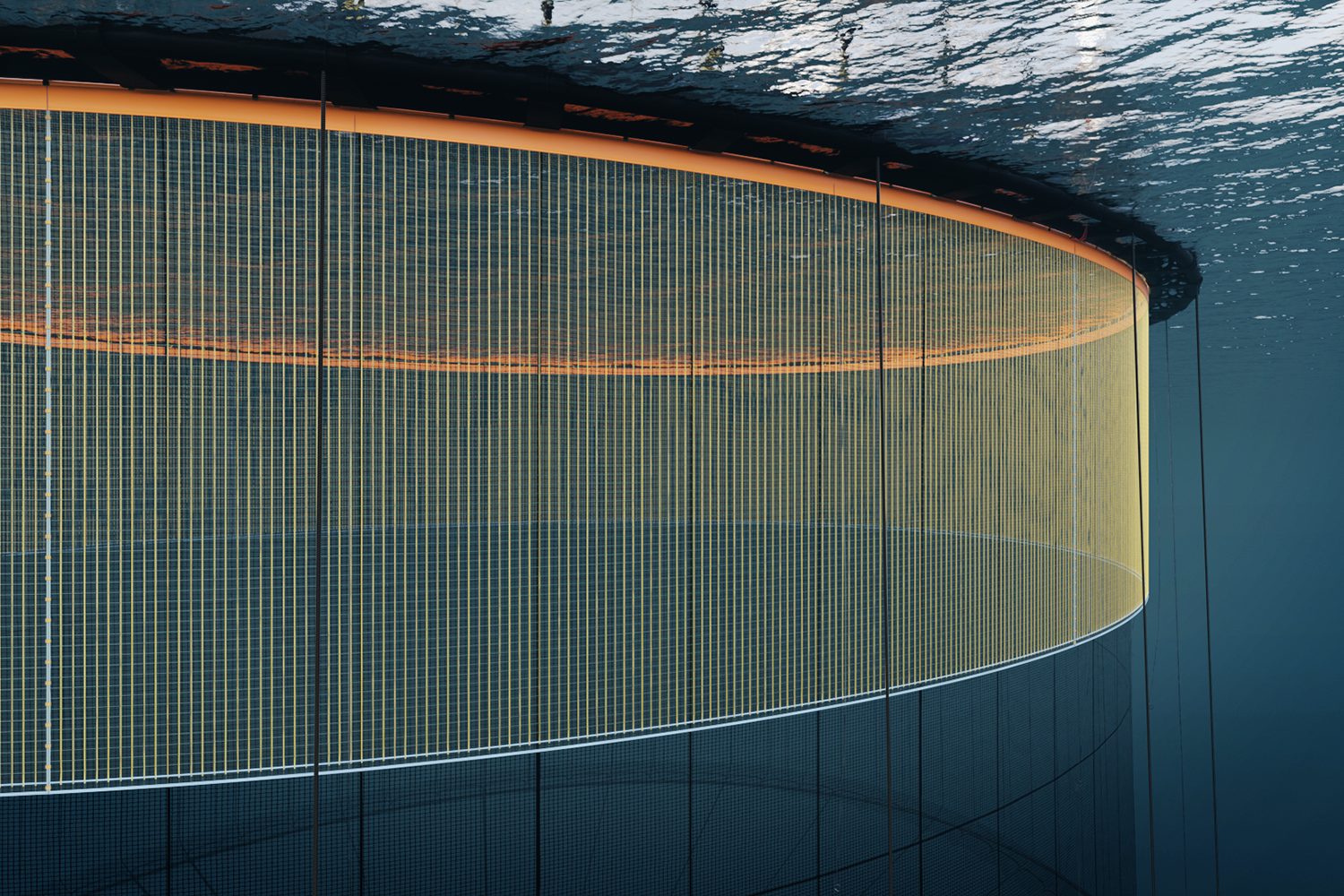

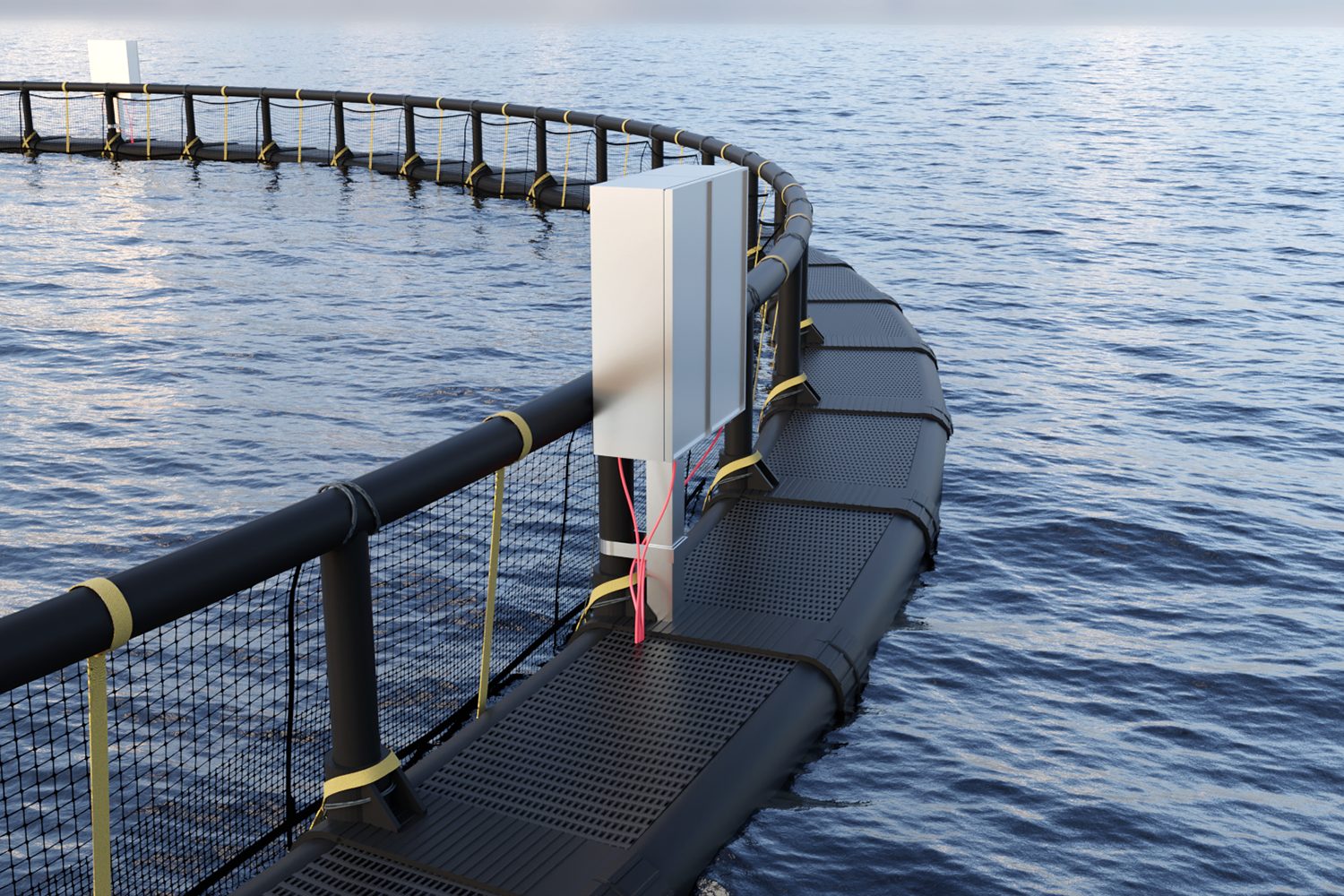

The Harbor fence generates electromagnetic fields with a frequency of 20 pulses per second using special electrode cables that are approximately 10 meters deep and hang outside the net pens. The fence’s size can be adjusted to suit different farms, while remote monitoring via cellphone makes it possible to optimize the frequency and length of the electromagnetic fields based on data such as salinity, temperature and current speed.

Trials have shown that sea lice can be immobilized during their free-swimming, early life, planktonic stage, also known as the nauplius and copepodite stages. Because the copepodite stage is the most infectious – when sea lice seek a host – intervening at this point reduces the risk of infection in farmed salmon, wild fish and neighboring farms.

“Our aim is to inactivate the sea lice during an important stage in their life cycle,” said Kleppa. “We also want to better understand what else happens to them when electromagnetic fields are introduced. For example, their ability to survive beyond the infectious stage, whether they can attach to salmon once they have been immobilized, and the extent to which variables like salinity and seasonal conditions impact electric fences.”

“There is also an element of fine tuning, for example if currents are strong and some lice drift into the pens without being exposed to electromagnetic fields,” said Helena Hauss, research director at NORCE Marine Ecology and BioSeaLice project leader. “We also need to understand the extent to which electric fences impact them – for example, whether they survive but aren’t able to find a host, or can’t reproduce as efficiently. The idea is to understand the basic biology of sea lice in response to innovative treatments.”

Harbor AS has also designed the fence to ensure its electromagnetic fields do not harm farmed salmon and other species in the wild.

“Fish don’t like a frequency of 200 hertz, while parasites don’t like the lower hertz range between five and 30,” said Kleppa. “The Harbor fence works in the lower hertz range, which is central to ensuring that fish health is maintained.”

Since electric fence technology has never been used on salmon farms, Harbor AS is working closely with researchers on every stage of product development – from installation and disassembly to remote monitoring and understanding the parameters that may influence the fences’ performance. They’re also addressing the challenges of targeting a tiny species that’s only one or two millimeters in size.

With 25 Harbor fences already installed on farms around Norway, Kleppa and Hauss are confident that the technology will benefit operating routines and overall salmon production. According to Hauss, the fences can also address other challenges, such as fouling on net pens and preventing the need for high pressure washing.

So far, the salmon sector has responded positively to Harbor AS’ solution, said Kleppa, reflecting a heightened awareness that preventive technologies are essential to tackle sea lice infestations. Looking ahead, the system will be tested in Chile and Scotland next year, following successful trials on the barbed wire jellyfish Apolemia uvaria, stinging jellyfish and other poisonous cnidarians that threaten farmed salmon. All of these species can be effectively neutralized by the Harbor fence, as its electromagnetic fields release their nematocysts, or stinging cells.

“The need to mitigate against sea lice is enormous, so the potential of this technology extends well beyond Norway,” said Kleppa. “While we develop the Harbor fence further, we are exploring additional application areas for the technology. For now, however, our focus is to optimize efficacy and develop the next version of the Harbor fence.”

“Salmon farmers need to reduce the pressure from sea lice,” said Hauss. “But it is beneficial to have a barrier that can stop sea lice from spreading during the planktonic stage, not just in farms but also into the environment, as this supports broader marine biodiversity goals. Soon, based on publications of our experiments, we hope to draw conclusions beyond the biological understanding of sea lice to innovation, and inform Harbor how to optimize.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Bonnie Waycott

Correspondent Bonnie Waycott became interested in marine life after learning to snorkel on the Sea of Japan coast near her mother’s hometown. She specializes in aquaculture and fisheries with a particular focus on Japan, and has a keen interest in Tohoku’s aquaculture recovery following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

A salmon farm in Dubai, because of course

Last year Dubai-based Fish Farm LLC sold the first batch of salmon to be born and bred in the United Arab Emirates. More are certainly coming.

Health & Welfare

Chem-free fixes emerging in sea lice saga

Salmon farmers, using emerging technologies, are exploring new methods of sea lice mitigation in an effort to overcome one of the industry’s most persistent problems. New chemical-free innovations show an industry eager to adapt and adopt environmentally safe practices.

Innovation & Investment

Could new technology transform how salmon farming combats sea lice?

Sea lice plague salmon farms globally, but scientists and aquaculture are turning to technology to prevent and manage the pests.

Health & Welfare

Scientists are developing a new ‘groundbreaking’ oral vaccine for sea lice in farmed Atlantic salmon

A new oral vaccine using reverse vaccinology and artificial intelligence may help with sea lice challenges faced by the aquaculture industry.

![Ad for [BioMar]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BioMar_seabream_web2025_1050x125.gif)