Results showed that fish exposed to human-caused noise had lower energy density, possibly causing system-level effects

Anthropogenic noise has been steadily increasing for the last few decades as human populations continue to grow, expand into new areas, and transport more goods across the globe. This noise has shown to have a range of negative effects on a variety of different animals, and there continues to be concern regarding the effects of noise on marine animals in particular. Although much of the literature focusing on noise in marine environments has historically focused on marine mammals, concern about its effects on other taxonomic groups found in marine habitats, including fish species has begun to increase, especially in light of the many other issues facing marine fish including overharvest and the rise in ocean temperatures.

Marine fish are negatively affected by anthropogenic noise in a variety of different ways. Noise can impact foraging success, and affect anti-predator behavior, movement patterns, breeding success, and increase stress. Studies to date have mostly focused on the direct effects of noise on the physiology or behavior of the specific organisms, but rarely do these studies consider the potential consequences of noise on interspecific interactions such as predator-prey relationships or other pathways of effects that can lead to larger system-level effects. Furthermore, the potential for noise to create large system-level effects, even when impacting only one species, is high especially when examining impacts on trophic interactions in particular.

There are surprisingly few studies that have investigated how noise affects forage fish even though these fish play a crucial role in the energy transfer from lower to higher trophic levels in the marine food web. If anthropogenic noise impacts the behavior of a fish species critical to an ecosystem (e.g., forage fish) that causes changes in its availability and/or quality as prey, then the cascade up the food chain could have important and potentially negative ecosystem-level consequences.

In order to take a more system-level perspective on the issue of anthropogenic noise we asked how noise may affect the quality of prey critical to the Northeast Pacific ecosystem. We chose Pacific sand lance (PSL, Ammodytes personatus) as it is a key forage fish, a critical source of food for many different marine species, especially Alcids (Auks or Alcids are birds of the family Alcidae), whose local reproductive success increases with sand lance abundance in the diet.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Carlson, N.V. et al. 2025. Noise results in lower quality of an important forage fish, the Pacific sand lance, Ammodytes personatus. Marine Pollution Bulletin Volume 213, April 2025, 117664) – discusses research that used playback recordings to investigate how different types of anthropogenic noise may affect PSL energy density, a key measure of food quality for their predators.

Study setup

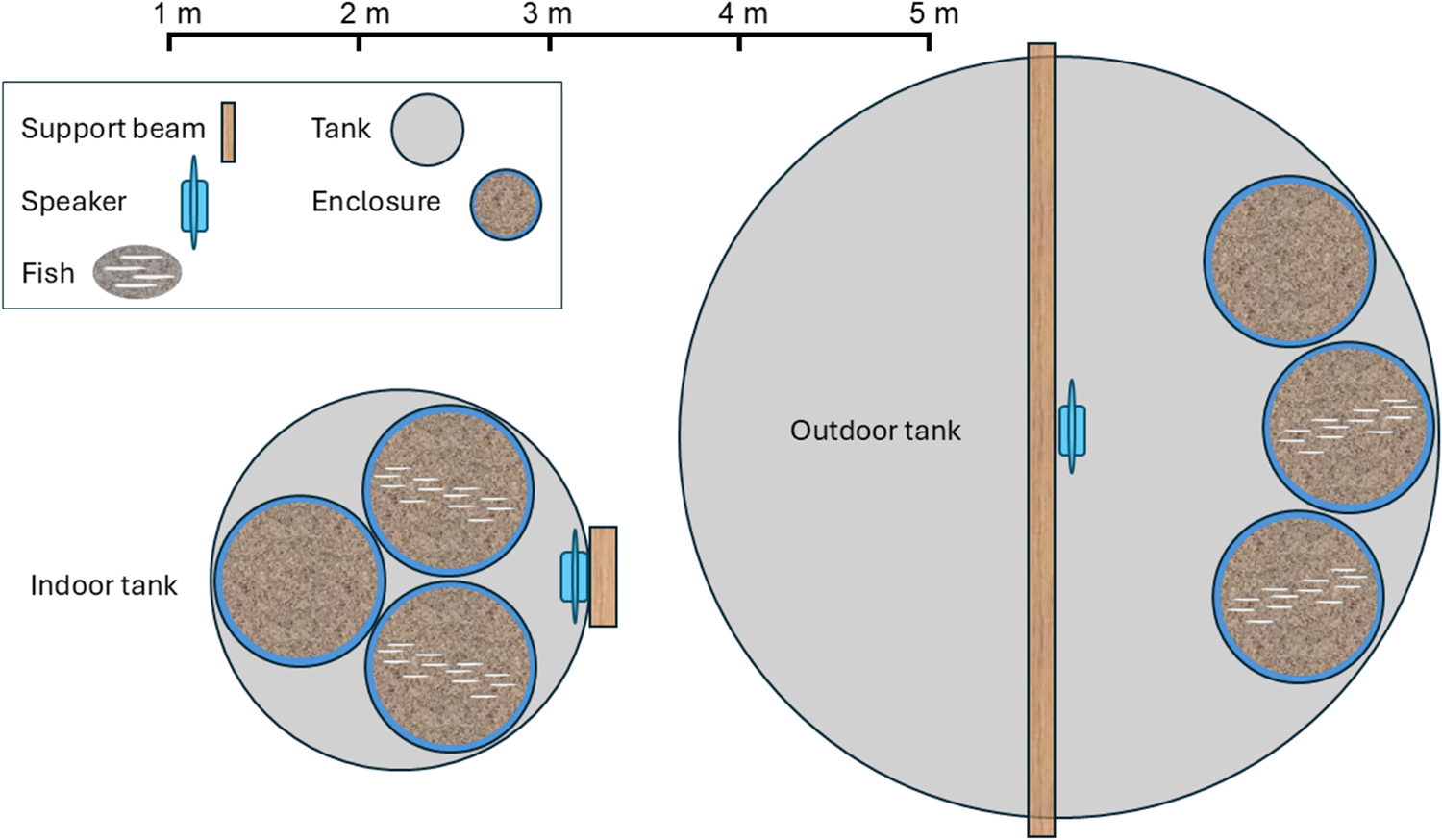

Using playback recordings, how different types of anthropogenic noise may affect PSL energy density – a key measure of food quality – for their predators, were investigated. A total of 345 PSL were collected with various nets at Jackson Beach and Eagle Cove on San Juan Island, WA, USA and transported to Friday Harbor Labs (FHL, University of Washington, Wash., USA). The fish were held in water-permeable circular enclosures (0.9 meters high x 0.8 meters diameter) within a larger concrete circular holding tank, indoors and outdoors (Fig. 1). The inside tanks were in a room with full windows on one side and experienced the same photoperiod as the outside tanks which were under a gazebo-like structure. The bottom of each circular enclosure had ~10–15 cm of sand collected from Jackson Beach (a location where PSL are known to bury throughout the year) to allow the PSL to bury as they do in the wild.

In order to simulate different types of anthropogenic noise which fish may be exposed to in the environments where they live, each tank received one of four possible playback treatments starting on day 7, for the duration of the 10 days of the experiment (4 tanks = 4 treatment groups): silence (control), wind farm noise, pile driving noise, and boat traffic noise. At the end of the experiment, fish were sampled and processed to determine size and energy density.

For detailed information on the experimental design, fish husbandry and data collection and analysis, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

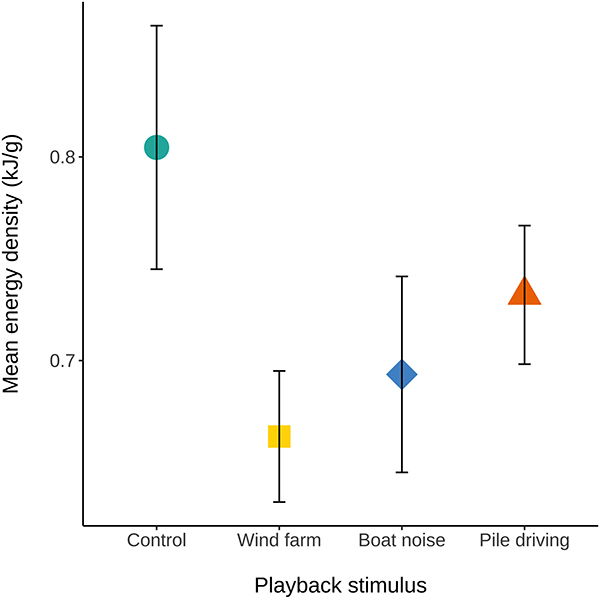

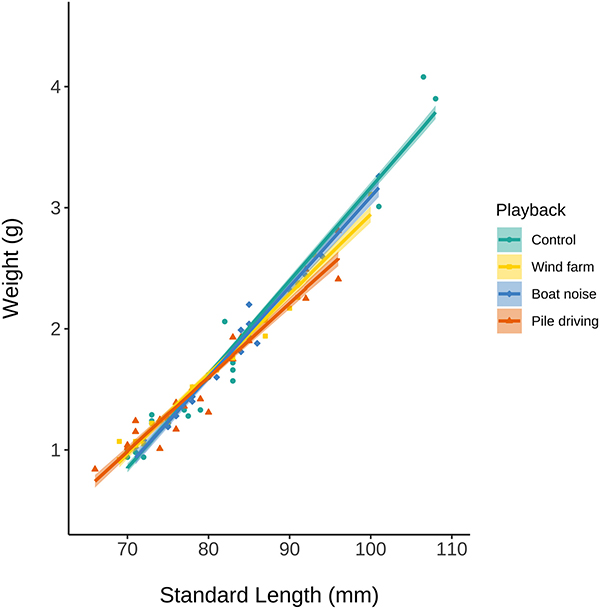

Fish in acoustic environments with anthropogenic noise playbacks had lower energy density (exposure to wind farm and boat noise) and reduced weight-at-length (exposure to wind farm and pile driving) compared to controls. These results suggest that PSL exposed to noise are of lower quality to their marine predators. As PSL are such an important food source for so many marine predators, especially breeding Alcids, decreases in PSL quality could have long-term and far-reaching effects on the marine predators that rely on them. While this experiment does have a clear result, it was intended to be a pilot experiment and therefore primarily serves to open further specific lines of inquiry regarding the effects of noise on PSL as an important source or prey, specifically in terms of habituation, behavior, and noise sources with trophic cascade implications.

While we demonstrate the acute responses of PSL to anthropogenic noise, if and how their response changes over longer periods of time remains to be determined. Further analysis of conditions more consistent with living in nearshore aquatic habitats during busy summer months and consideration of both cumulative effects and potential acclimation should be explored. The trend we see in our data could be an acute response and PSL could slowly habituate or acclimate over time, lessening the effects of noise. Such habituation has been seen in other fish species exposed to noise, including European seabass and domino damselfish. Conversely, the negative effects of noise could remain constant, as seen in Atlantic cod and other fish species, or compound, increasing the impacts of this noise as it continues to persist in the environment – potentially also increasing any differences between noise types.

The decreases in the quality of the PSL exposed to noise, though possibly a result of physiological responses such as stress, are likely due to changes in behavior as commonly seen in responses to noise. For example, changes in behavior in response to noise could impact PSL condition either through increased energy expenditure (by increasing energetically costly behaviors like startling, decreased foraging success directly by increasing mistakes, or indirectly by altering time budgets (e.g., increased vigilance, or special use (e.g., spending more time in areas with poorer quality food such as lower in the water column or in different areas which could lower their food intake.

These behavioral changes could also affect PSL predators, not just impacting the amount they would need to forage to make up for less energy dense prey, but also if prey availability was reduced (e.g., prey spending more time buried). A reduction in energy content of forage fish has resulted in significant impacts on Alcids in the past. We show an ~14 percent decrease in energy density from average control to average noise condition fish. This value is lower than the estimated 25–35 percent lower bill load energy content for marbled merlettes during the marine heat wave, though still likely a large enough difference in energy requiring an increase in foraging effort to maintain adequate energy for chicks.

While studies on the effects of noise on fish have examined a range of noise sources, the majority of studies tend to focus only on one at a time though there are exceptions. However, due to the different temporal and frequency profiles of most anthropogenic noise, different noise sources likely have different types of effects on fish behavior and physiology. One of the initial intentions of this pilot experiment was to determine if PSL respond differently to different sources of noise. While this was not explicitly evaluated in this paper, there appears to be some slight differences in fish response to the different acoustic conditions that they encountered, which agrees with other studies. However, the relationship between noise sources and effects on individuals remains poorly understood as different studies address slightly different types of questions when investigating different sound sources making comparison across studies difficult.

Additionally, we did not address particle motion in this experiment in either the water or sediment as we did not have access nor funds to acquire the specialized equipment necessary to measure particle motion accurately, which limits the conclusions of this study. Based on our current understanding about both the relationship between sound pressure and particle motion in both water and sediment, and how it is likely to affect marine organisms, it is likely that the particle motion may impact PSL slightly differently than sound pressure. In open water, particle motion and SPL are quite similar in most respects and one can be relatively reliably determined from the other. However, in tanks and fish held in captivity, SPL and particle motion can act differently. Additionally, when examining SPL and particle motion in different substrates, there can be differences as well.

Anthropogenic noise reflects one among many potential threats to PSL. This species spends considerable time in benthic sediments throughout this region concentrated in discrete habitats, often at extremely high densities. Important life history events occur during residence in benthic sediments, including gonadal maturation and important reproductive processes. Reduced condition and energetics related to noise disturbance may not only influence quality of this prey but also reduce overwinter survival and reproductive output. The relative impact of noise sources explored might depend on the location. Boat noise and pile driving likely have the greatest impact in nearshore habitats or areas used for foraging. These sources of noise are unlikely to impact PSL at depth in benthic sediments, sometimes >80 meters deep and offshore. Wind farms and pile driving may have important impacts in habitats such as shallow glacial banks, extensive areas known to be important to PSL.

Mitigation of potential adverse impacts would require additional data to strengthen evidence for these effects. As applied in a precautionary manner, however, our results suggest the need to consider noise impacts in assessments of locations for wind farms, oil exploration, resource extraction, or the development of structures requiring physical alteration to habitat (i.e., pile driving, construction, dredging, drilling, resource mining). These are recognized threats to sand lance and sand eel populations in the western North Atlantic and the North Sea. While many of these studies have examined potential impacts to distribution and behavior, few have examined impacts to condition and quality; this is an area warranting further research.

Perspectives

Study results demonstrate that even mid-term exposure (days to weeks) to low-levels of anthropogenic noise can affect the energy density and weight/length relationships of an important forage fish and suggest that the effects of noise on any one organism are not limited, but have the potential to cause significant ecosystem-level effects cascading up trophic levels.

This finding highlights the critical importance of understanding, not only how noise affects individual species, but how it can alter ecosystems much like the effects of climate change and pollution. The more we learn about the effects of noise, the more we can begin to quantify the negative and potentially wide-reaching consequences of the increasing disturbance we are creating in our oceans.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Nora V. Carlson

Corresponding author

University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC V8P 5C2, Canada[109,111,99,46,108,105,97,109,103,64,110,111,115,108,114,97,99,46,118,46,97,114,111,110]

-

Meredith A.V. White

University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC V8P 5C2, Canada

-

Jose Tavera

Universidad del Valle, Ciudad Universitaria Meléndez, Calle 13 # 100-00, Santiago de Cali, Valle del Cauca, 760042, Colombia

-

Patrick D. O'Hara

University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC V8P 5C2, Canada

-

Matthew R. Baker

University of Washington, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, Seattle, WA 98105, USA

-

Douglas F. Bertram

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Integrated Marine Spatial Ecology Lab, Institute of Ocean Sciences, 9860 W Saanich Rd., PO Box 6000, Sidney, BC V8L 4B2, Canada

-

Adam Summers

University of Washington, Friday Harbor Laboratories, 620 University Rd., Friday Harbor, WA 98250, USA

-

David A. Fifield

Wildlife Research Division, Science and Technology Branch, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Mount Pearl, NL, Canada

-

Francis Juanes

University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC V8P 5C2, Canada

Related Posts

Fisheries

Can electronic tags fill knowledge gaps between offshore wind and fisheries?

A first-of-its-kind study will explore fish behavior in response to offshore wind turbines and construction activities in the Atlantic Ocean.

Responsibility

Ocean noise: How the changing sea soundscape can stress fish

Ocean noise from human activity can change fish behavior like feeding, but new technologies and techniques can minimize the stress.

Responsibility

Net-zero heroes: Hybrid and electric commercial fishing vessels set out to cut the industry’s carbon emissions

From electrified fishing fleets to hybrid wellboats, the seafood community is looking to decarbonize commercial fishing vessels and reduce carbon emissions.

Innovation & Investment

The artificial intelligence of things and its aquaculture applications

Artificial intelligence of things, or AIoT, is solving aquaculture challenges related to operational efficiency, sustainability and productivity.

![Ad for [f3]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/F3_web2026_1050x125.jpg)