Improver programs and branding opportunities provide an opening for the sector to make a fresh mark

Shrimp farmers in Bangladesh have long sought to plow a much more commercially viable furrow. While the industry has successfully ramped up its harvests in recent decades to a level exceeding 30,000, the long-term overriding goal for Bangladesh shrimp has been for products to compete and thrive in world markets so that they optimize the value for those on the ground. Now though, market forces may offer a way for these hopes to become a reality.

Historically, the Bangladeshi vision has been stopped in its tracks by the composition of a production sector that’s predominantly built on the extensive culture of black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon), and which comprises many thousands of smallholder farms, largely in quite remote areas. Indeed, while the farming of black tigers – known domestically as “bagda” – spans some 150,000 hectares, the majority of these operations are only around 1 hectare each in size. Moreover, most of these low-yield, poverty-threatened producers have no option but to operate through a large network of middlemen, who can in turn detract from the product quality.

Not only have these circumstances made shrimp farmers in Bangladesh slower in their uptake of new technologies and farming practices than in other production regions they’ve also made it extremely difficult to train, track, improve and reward them.

Global Seafood Alliance (GSA) President George Chamberlain suggests the emerging opportunity for Bangladesh to make some headway and for farmers to obtain fair and equitable prices lies in the limited availability of globally farmed seafood that’s certified to market-recognized certification programs such as Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) and the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC). He estimates this to amount to just 4 to 5 percent of the total production, with considerable crossover between the two schemes.

While meeting such standards is probably not an option for many at present, Chamberlain believes what puts the uncertified back within reach is that many seafood buyers who, thwarted in their pursuit of large volumes of certified products, are increasingly seeking to source products from suppliers that are engaged in fishery improvement projects (FIPs) or aquaculture improvement projects (AIPs). This purchasing strategy is with the proviso that those in the improver programs have definitive and ambitious goals, as well as measurable metrics and timebound milestones.

“Buyers are willing to accept that many producers are on a journey,” Chamberlain said, maintaining that a logical place to begin with AIPs is with large-size, high-value black tiger shrimp in Asia, which puts Bangladesh firmly in the frame. And a key message that he delivered to both the Seafood Expo North America (SENA) in Boston and then the Seafood Expo Global (SEG) in Barcelona is that retailers, processors, government representatives, funders, certification bodies and other NGOs all have a role to play in developing these AIPs.

Brand benefits

Offering some product insight, Chamberlain said a crucial advantage for producers of black tigers is that when cultivated in low densities, “their quality is spectacular, and they look just like wild shrimp.”

The species can grow rapidly to large sizes with natural pigmentation and offer low carbon footprints, he said, adding that not only does this make them intrinsically valuable to Bangladesh, it provides the platform from which to form clusters of farms that can sell premium-quality shrimp directly to processors.

In turn, this offers the means to give farmers a fair return on their harvests and help them “double or even triple” their productivity using improved practices, he said. They could also collectively progress towards certification.

But the big challenge in all this is the sheer number of small farms that will require improver programs and coalitions, Chamberlain said.

“Imagine 150,000 small farms that must be organized and improved. This is not just in Bangladesh. In Cau Mau there are 88,000 hectares of extensive farms and more in other provinces of Vietnam, as well as in Indonesia, India, the Philippines, and on and on. But it’s a huge opportunity for a lot of people,” he insisted.

Moving forward and to assure market acceptance across production regions, Chamberlain advises that a common international brand complete with product quality and size standards should be developed – something along the lines of “Premium Natural Tiger Shrimp.” The word, “Natural”, would be based on use of low stocking density and no additives such as polyphosphates or bisulfites.

With rigid product specifications, this branding should differentiate the products from Pacific white or whiteleg shrimp (Litopanaeus vannamei) and black tiger shrimp of mediocre quality, he said.

“Vannamei has become a commodity, so there’s an opportunity to provide a distinctive, higher-value product,” Chamberlain said.

Meanwhile, on the ground, and to help smallholder farmers increase their productivity and efficiency, higher quality inputs should be provided, including sufficient quantities of specific pathogen-free (SPF) post-larvae produced from genetically improved broodstock, high-quality feeds (potentially low carbon or organic), together with improved management assistance.

Local leadership

From his experience sourcing different shrimp species from various regions for retail businesses, Dominique Gautier of the Sea Fresh Group explained that a tried and tested way to bring products from small-scale farmers to market is to form a cooperative body or have a main local buyer that organizes farmers into a group (cluster) that controls production processes.

Alongside this, a clear code of management practices – covering risks to products, people and the environment – must be agreed upon with compliance a condition of participation.

He told the SEG gathering that specifically for market access, the code of management practices must cover:

- Traceable inputs and outputs

- Responsible sources of post-larvae and feeds

- Use of chemicals and medicines

- Pathogen and disease control

- Any impacts on water resources and biodiversity

- The provision of good working conditions and community relations

In this regard, local buyers and/or processors have a key role to play, said Gautier, particularly in ensuring food safety from harvest to processing and preserving quality.

He added that buyers also can support farmers by pre-funding certain inputs as well as facilitating access to good broodstock and in other areas where agreed-upon standards must be complied with. Another way they can provide invaluable help is by ensuring documentation of compliance, including traceability, to either allow for verification to agreed conditions or for application to a third-party certification.

Though not easy to put in place, an internal control system will be required for third-party verification and group certification, he said.

“In any case, the approach needs to be practical and flexible and consider specific circumstances related to the risks of these farming systems and location,” Gautier said. “They must also limit procedure and documentation requirements as much as possible to keep as simple as it can be, while verifying compliance based on data collection and on-site observations.”

Breaking the cycle

Telling the same audience that Bangladesh has plans to double its shrimp production and earn more from the industry, including obtaining more overseas currency from exports, Director General of the Department of Fisheries Kh. Mahbubul Haque confirmed that around 300 clusters have already been established, each comprising some 25 smallholder shrimp farms.

“We are taking special care of our shrimp, especially the black tigers,” he said.

With the increasing importance of meeting traceability requirements, and “the hope that more buyers and exporters will take part in the system,” each of these clusters has been organized whereby they use the same sources of water, juvenile animals and (where needed) feeds, Haque clarified. The first crops were expected in July.

“We are very conscious of the importance of quality, and our hope is farmers in the clusters will be able to at least double their production without using any new technologies. For now, we’re just asking them to increase the water depth because the low depths in ponds have resulted in mortalities,” said Haque. “We’re working for the betterment of these poor fish farmers. But as well as protecting the farmers, I hope it will also help their communities.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Jason Holland

Jason Holland is a London-based writer for the international seafood, aquaculture and fisheries sectors. Jason has accrued more than 25 years’ experience as a B2B journalist, editor and communications consultant – a career that has taken him all over the world. He believes he found his true professional calling in 2004 when he started documenting the many facets of the international seafood industry, and particularly those enterprises and individuals bringing change to it.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

Assessing the effects of low pH on taste, amino acid composition of black tiger shrimp

The effect of low pH on the survival and amino acid composition of shrimp suggests ocean acidification may affect future quality, quantity.

Innovation & Investment

Innovation Award 2020 finalist: Simao Zacarias’ shrimp eyestalk ablation research

Farmed shrimp eyestalk ablation research is one of three finalists for the Global Aquaculture Alliance’s annual Global Aquaculture Innovation Award.

Health & Welfare

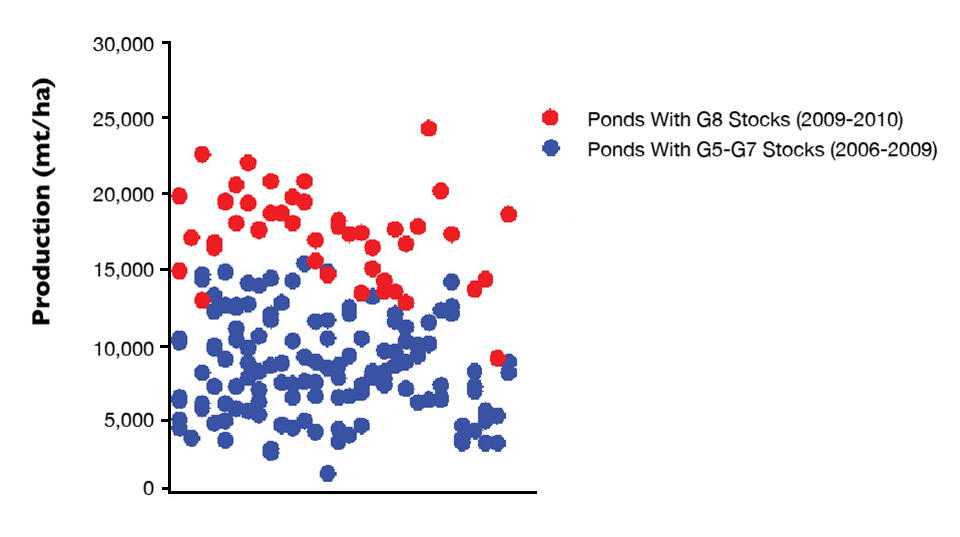

Black tiger breeding program yields record shrimp harvests in Australia

Traditionally, Australian farmers relied on wild broodstock to source black tiger shrimp larvae, but substantial progress has been made in the domestication and selective breeding of Australian P. monodon.

Intelligence

Can India sustain its farmed shrimp boom?

Long a global leader in farmed fish production, India has transitioned into an aquaculture powerhouse. Can its expanding shrimp sector keep the rapid pace?