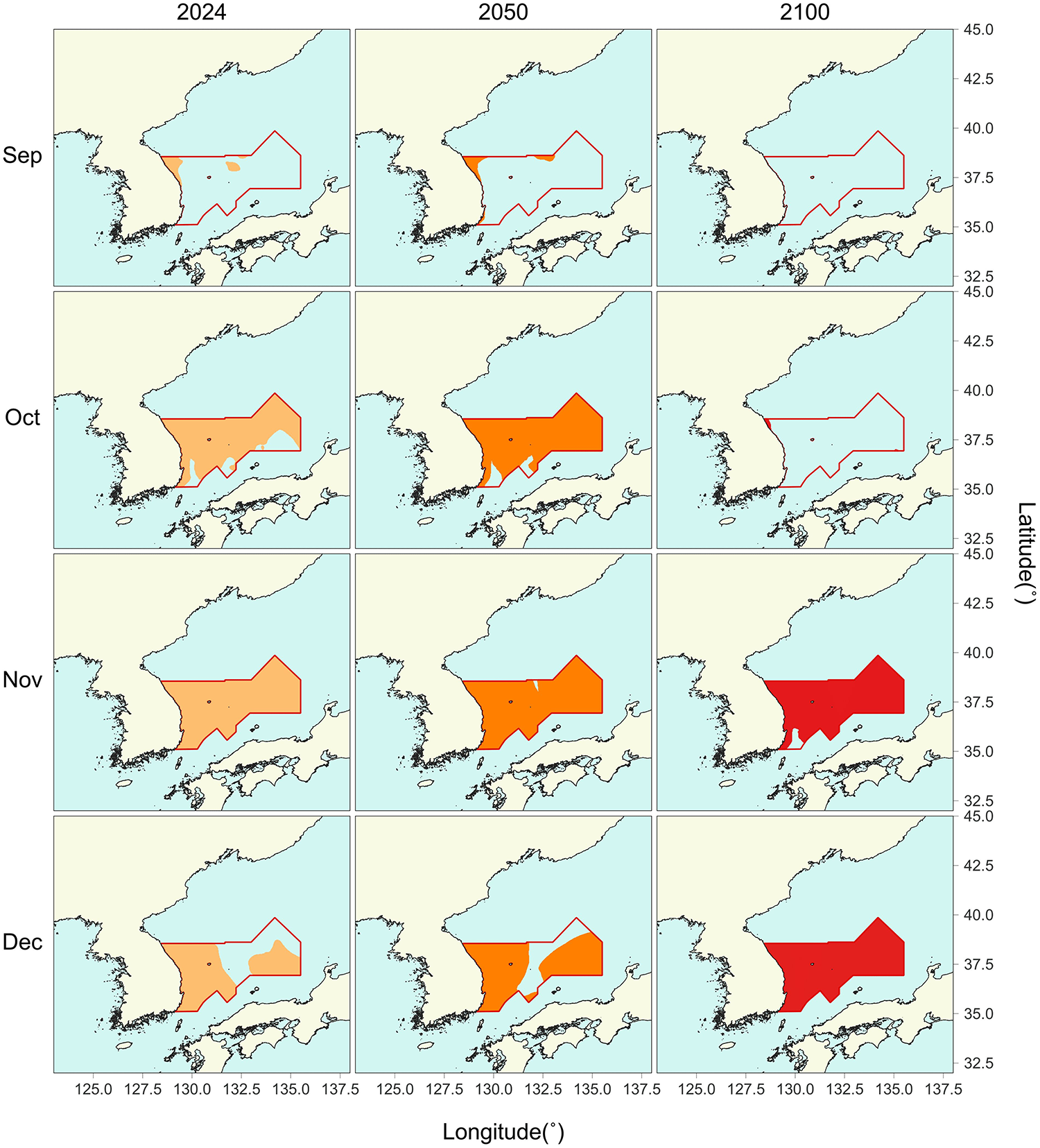

Results indicated a contraction of suitable fishing areas in the main season (September–October) with suitable temperatures reemerging in November

Rising sea temperatures are a major driver of ecological responses in marine organisms, altering population maintenance and reproductive strategies, and ultimately leading to shifts in habitats or distribution ranges. These responses vary by species, depending on physiological tolerance and behavioral traits, with species more sensitive to environmental change exhibiting a greater likelihood of distributional shifts. In fact, changes in the distribution of various commercially important species have been observed in response to ocean warming, affecting fishing activities and resource utilization patterns.

The Korean coastal and offshore waters, particularly the eastern waters of Korea, represent a transitional zone where the subtropical Tsushima warm current and the subarctic Liman cold current converge, resulting in pronounced ecological responses to sea temperature changes. Within these environmental conditions, the common squid (Todarodes pacificus) is recognized as a representative climate-sensitive species. As a short-lived, fast-growing and highly migratory species, T. pacificus exhibits substantial shifts in its distribution range and fishing ground centers in response to changes in ocean conditions. In particular, in the eastern waters of Korea, the species responds sensitively to variations in water temperature and the position of thermal fronts, resulting in distinct seasonal and interannual differences in the spatial distribution of fishing grounds.

We hypothesize that the abundance of T. pacificus – as reflected in its catch per unit of effort (CPUE, an indirect measure of the abundance of a target species) – is influenced by spatiotemporal variability and sea surface temperature, and that the species exhibits a preferred thermal range, with suitable habitats expected to shift geographically under future climate scenarios. This hypothesis is consistent with previous findings for T. pacificus and other squid species in various regions, which have reported SST and season dependent changes in distribution. The novelty of this study lies in applying this established ecological framework specifically to the Korean offshore jigging fishery and in explicitly integrating the preferred thermal range, estimated from standardized, fishery-dependent CPUE, with scenario-based sea surface temperature (SST) projections from a high-resolution regional ocean model for Korean waters.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Kim, M-J. et al. 2025. Forecasting the spatial variation of optimal sea surface temperature for common squid (Todarodes pacificus) in the Korean jigging fishery. Front. Mar. Sci., 31 August 2025, Sec. Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources Volume 12 – 2025) – presents the results of a study to standardize the catch per unit effort (CPUE) of common squid in Korean waters, specifically in the offshore jigging fishery, by incorporating spatiotemporal and sea surface temperature (SST) factors, and to assess future shifts in thermally suitable fishing grounds.

Study setup

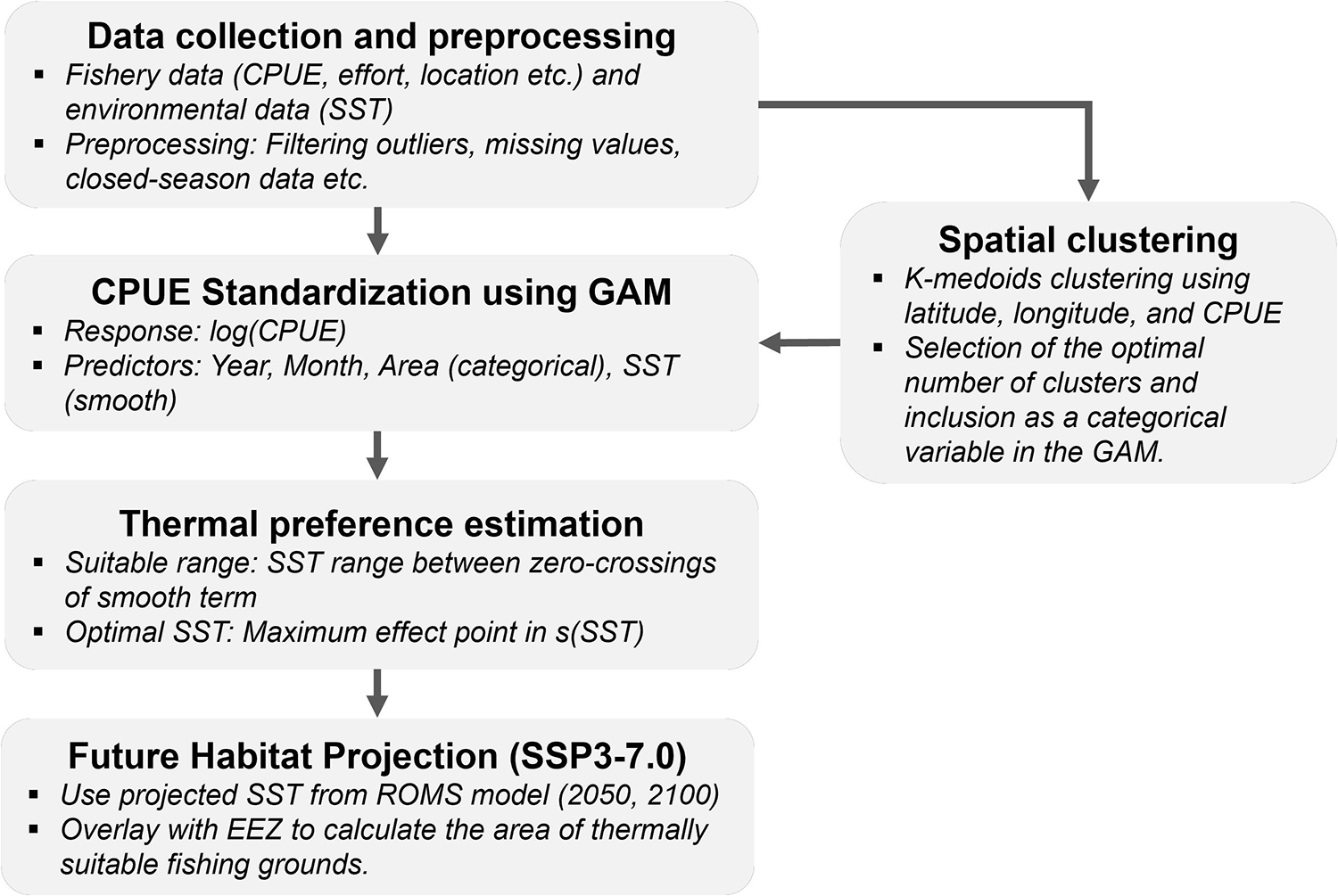

The overall analytical process in this study consists of five sequential stages: (1) data collection and preprocessing; (2) spatial clustering; (3) CPUE standardization using a generalized additive model, GAM; (4) thermal preference estimation; and (5) future habitat projection under a Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP. SSP3-7.0) climate scenario.

In this study, a generalized additive model (GAM) was applied to standardize the CPUE of the offshore jigging fishery for common squid by incorporating operational and SST-related covariates.

Generalized additive models (GAMs) are particularly effective for incorporating multiple factors, as they flexibly capture nonlinear relationships between environmental variables and spatial structure. Due to these characteristics, GAMs have been widely applied to fishery survey data to investigate how environmental factors influence the distribution patterns of marine species. We also estimated the species’ preferred thermal range from GAM analysis, which was then used to identify suitable fishing grounds under future, projected SST conditions.

For detailed information on the experimental design, and data collection and analysis, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

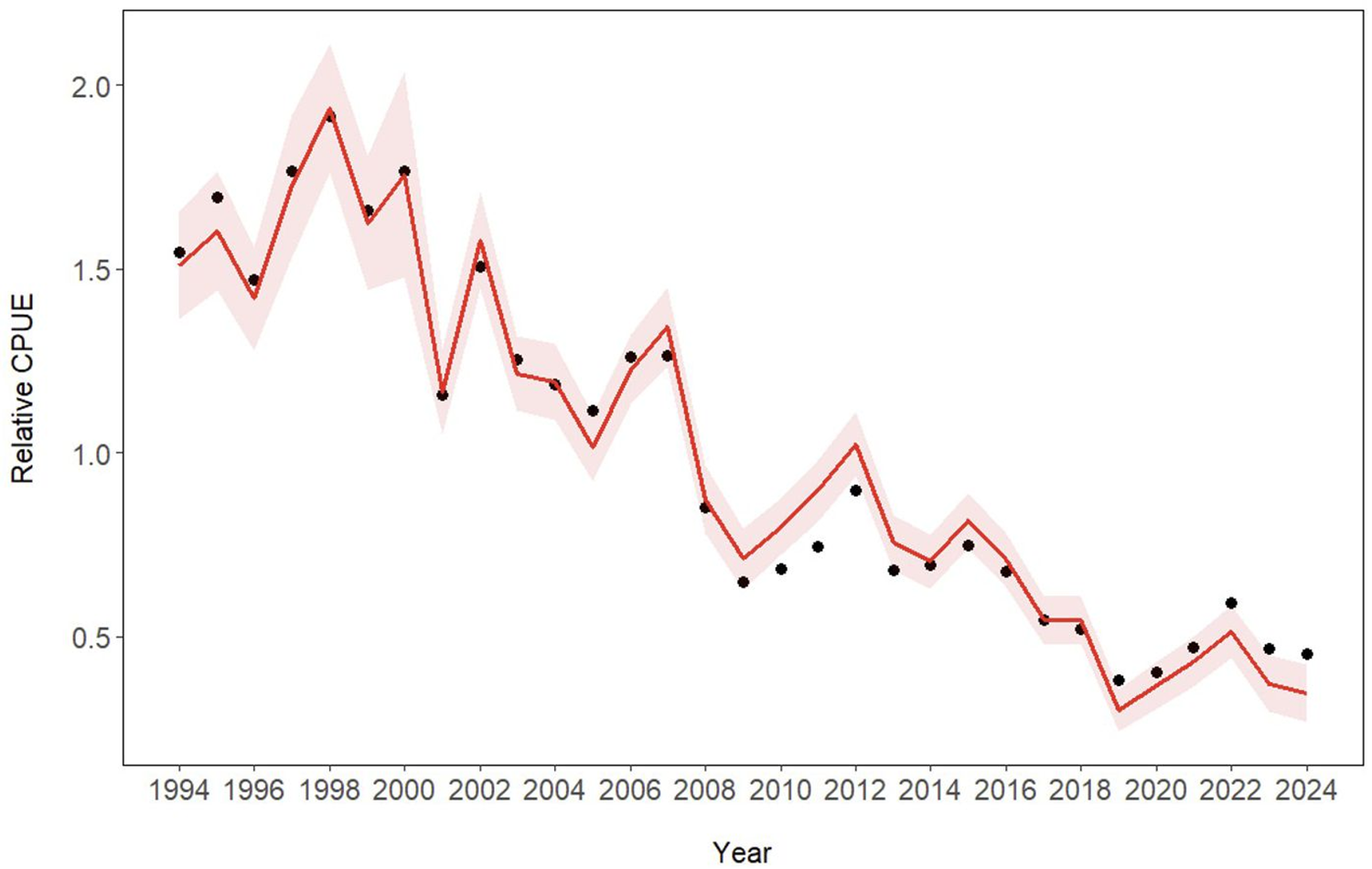

This study quantified future shifts in the fishing ground distribution of common squid in the eastern waters of Korea under a specific climate change scenario (SSP3-7.0), by standardizing CPUE data from the coastal jigging fishery and incorporating spatiotemporal and oceanographic variables. The generalized additive model (GAM) used revealed a significant nonlinear relationship between CPUE and SST, with positive effects observed within the 13–23 degrees-C range.

The highest CPUE was detected near 21 degrees-C, which was identified as the optimal temperature, while 13–23 degrees-C was defined as the species’ suitable thermal range. Compared to the broader thermal tolerance range of 5–27 degrees-C reported by other researchers, the refined range identified in this study reflects temperature conditions more closely associated with active fishing grounds. These results provide ecologically grounded temperature thresholds that can serve as a foundation for forecasting future habitat suitability under climate change.

Under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, projected SST distributions for 2050 and 2100 indicated a progressive northward shift and reduction in the spatial extent of areas meeting the suitable thermal range for common squid during its peak fishing season (September–October). Notably, by September–October 2100, suitable thermal habitats may disappear from the southern part of the eastern waters of Korea, suggesting potential constraints on the availability of traditional fishing grounds. In contrast, suitable conditions are projected to reemerge in the southern part of the eastern waters of Korea in November and remain available through December, implying a possible delay in the timing of fishing ground formation (Fig. 3).

These results suggest that climate change may not only alter the spatial distribution of squid fishing grounds but also shift the temporal window of fishing activities. As the fishable area is expected to contract or shift seasonally in response to ocean warming, adjustments to current fishing practices may be required. This highlights the need for adaptive strategies, including revisions to fishing seasons, adjustments in management benchmarks, and the development of predictive, climate-informed fisheries management.

While the thermal range identified in this study reflects the biological temperature preference of common squid, it is important to note that the CPUE data used were limited to areas where commercial fishing operations were conducted. As a result, the estimated thermal preference range may be influenced not only by the actual ecological distribution of the species, but also by fishing behavior and gear-specific selectivity. Such biases are inherent to fishery-dependent data, where observed catch rates can reflect where fishers choose to operate rather than where the species is most abundant. Future studies should adopt an integrated approach that combines standardized CPUE data with biologically derived temperature preferences from the literature and fishery-independent data – such as acoustic monitoring, larval sampling, and seasonal trawl surveys – to improve the precision and ecological validity of habitat models under climate change.

The thermally suitable range and climate-based habitat projections presented in this study can serve as foundational information to support more adaptive and forward-looking management. Future efforts should focus on establishing climate-resilient strategies that incorporate predictive tools, flexible fishing schedules, and revised resource management criteria. In particular, spatially dynamic seasonal closures, regionally reallocated total allowable catches (TACs) and habitat-based access regulations should be considered to more directly address catch declines and shifting squid distributions under climate change. Additionally, given the transboundary nature of squid distribution, future cooperative management frameworks – particularly with neighboring countries such as Russia and others – may be essential to ensure sustainable harvests under shifting oceanographic conditions.

Could squid aquaculture fill the gap from declining cephalopod stocks in Japan?

Perspectives

This study standardized the catch per unit effort (CPUE) of T. pacificus in Korean waters using a generalized additive model (GAM) that incorporated spatiotemporal and sea surface temperature variables and assessed future changes in thermally suitable fishing habitats under the shared socioeconomic pathway 3-7.0 (SSP3-7.0) climate change scenario. The model revealed a significant nonlinear relationship between CPUE and sea surface temperature (SST), with a suitable thermal range of 13–23 degrees-C and an optimal temperature near 21 degrees-C. Rather than forecasting future CPUE values, we applied these thermal thresholds to projected SST, which indicated a northward shift and seasonal delay in thermally suitable fishing grounds, especially under the 2100 scenario.

These findings suggest that climate change is likely to affect not only the spatial distribution of squid fishing grounds, but also the timing of peak fishing seasons. As traditional fishing grounds in the eastern waters of Korea may become unsuitable during the autumn months, suitable habitats are projected to reemerge later in the season, indicating the need for flexible and adaptive management strategies. Although the analysis was limited to SST as the sole environmental factor and relied on fishery-dependent data, it provides a useful basis for identifying future thermally suitable habitats.

Future studies that incorporate broader environmental variables and fishery-independent data could improve model accuracy and ecological relevance. These results may inform the development of operational habitat forecasting systems designed to enhance flexibility in future fishery management.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Moo-Jin Kim

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, Republic of Korea

-

Changsin Kim

Ocean Climate & Ecology Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, Republic of Korea

-

Hyun Woo Kim

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, Republic of Korea

-

Hwan-Sung Ji

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, Republic of Korea

-

Heejoong Kang

Corresponding author

Coastal Water Fisheries Resources Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, Republic of Korea[114,107,46,97,101,114,111,107,64,55,56,106,104,103,110,97,107]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Could squid aquaculture fill the gap from declining cephalopod stocks in Japan?

With declining squid populations, researchers in Japan have developed the first aquaculture system with potential for commercialization.

Health & Welfare

A perspective on shrimp larviculture and liquid larval diets

A prominent shrimp farm and hatchery in Venezuela has tested microparticles, microencapsulated particles and liquid larval diets.

Fisheries

Assessing the effect of seafloor plastic litter on fishing economic performance and commercially important Mediterranean species

Study suggests a threshold level of seafloor plastic litter density to ensure the sustainability and profitability of commercial fishing.

Fisheries

Comparing fishing catch efficiency of self-baited, ghost snow crab pots and actively baited pots in the Barents Sea commercial fishery

The impact on the marine environment caused by ghost fishing gear is not always increasing due to self-baiting and can vary during exposure.

![Ad for [Aquademia]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/aquademia_web2025_1050x125.gif)